My mom has a common, if unspoken, love language: worry. She responds to every bit of good news with foreboding concern. When I completed high school, she warned me to be extra careful: “Haven’t you heard about that kid who died in a car accident right after his high school graduation? Bad things happen right after good things happen.”

When I got engaged and texted my parents a photo of the ring, she and my father responded, “Too expensive. You’ll lose it.”

When I made partner at my former law firm, they were despondent: “So stressful, more of the same life!”

And when I told them I had left the firm: “So stressful, starting over!”

During a slow week in my first year of law school, I celebrated by treating myself to a one-hour nap in the afternoon. When I awoke, I had twelve missed calls from my mother, three voice messages, and a text informing me of her fears that I had been abducted, and then another indicating that she was preparing to call both campus police and New Haven police.

A decade later, when I secured my book deal, it took me six months to ready myself to share the news with her. And when at long last I did, I sat through an hours-long lecture about how when people become famous, they become prone to substance abuse and suicide, and why couldn’t I just live a peaceful life?

I’ve confronted her a few times about this: “Why can’t you just be happy for me, proud of me? There’s no need for all the negativity.”

No matter how quickly I run and how far I get, my mother insists on being the crossing guard two blocks ahead of me, pointing out the Mack truck that’s just waiting to mow me down at the earliest opportunity. It’s become such that when a good thing happens to me, I clutch it close to my chest, knowing that the minute I share it with her, she will douse me with the ice cold water of reality. Haven’t I learned by now? We earn the good news by enduring the catastrophe to come. Good news always gets us back.

I’ve confronted her a few times about this: “Why can’t you just be happy for me, proud of me? There’s no need for all the negativity.”

Each time she responds along the same lines: “You will understand when you’re a mother. You are flesh that fell from me! Good things happen to you because I pray against the bad things.”

Or, more threateningly: “One day you will appreciate it, when your mother is dead and there is no one to worry for you.”

But neither of those things have had to happen for me to inherit native fluency in my mother’s love language.

When I went off to college, I spent an hour every day on the phone with her, and then spent the remaining 23 hours each day with the fear curled up at the back of my brain, the one that whispered that my parents would die any minute. When I finally had to forgo the hour-long phone call due to the demands of my lawyering hours, I switched to texts throughout the day. And the fear shrieked even if my parents responded with just a moment’s delay.

And later, whenever I traveled for business, I grew convinced that my husband and our dogs would die in my absence. Short of my presence, my worrying from afar was the only thing to keep my loved ones safe and alive. And when any sort of good news descended upon us, I held my breath, waiting for an anvil to materialize in the sky just to land on our heads.

Getting to know my in-laws was eye-opening. When my husband and I returned home from a gathering with them, they never pelted our phones with calls and texts making sure we had arrived safely. In fact, they often didn’t follow up at all.

I couldn’t help but wonder: Why don’t they care that we might have died?

--

My parents’ childhoods were defined by China’s Cultural Revolution, a decade of upheaval and bloodshed in which millions were subjected to imprisonment, torture, hard labor, and exile. People all around them quite literally disappeared overnight, for crimes as simple as being intellectuals or landlords.

Even my comparably well-positioned maternal grandparents were sent away for “reeducation,” leaving my mother in charge of her two young brothers. She recounts often to me her recollections of the historic Tangshan earthquake the summer she was 13, when a 7.5 Richter scale event rocked the town in the dead of the night. Then in sole custody of her brothers, one eight years old and the other a mere toddler, my mother still recalls awaking from peaceful sleep to see the earth open up beneath her. She remembers grabbing her brothers, still half asleep but already crying, and shielding their heads as they three stood in the doorway while the rest of their home came down all around them.

All of the devastations of my mother’s life came on suddenly, without warning. When I was little, she told me that worrying was how we warded the bad things off. If we worry about something, it won’t come into fruition. It was the stuff we didn’t think about — the stuff that came on while we were in deep, trusting sleep — that became the largest calamities. Her solution to keep her family safe: worry about absolutely everything.

But whenever my adult self shows signs of her habitual worrying, she lectures me. “Why do you spend so much time worrying? Go live your life!”

This hypocrisy used to leave me irritated and confused until one day, I heard her repeat her favorite saying: “You are smart because your mother is dumb. That’s just how it works.” I had heard her say this countless times before, each time smarting at the thought of my talented, wise mother believing herself stupid. But this time, scenes from my childhood flooded back and clicked into place.

Whenever I did chores growing up, my mother often told me to stop, to do something worthwhile instead. “As a kid, all I did was chores. It left me so naïve.” Whenever my grandparents fought, she said, they would hide it from her. Perhaps because she was a girl, they shared with her none of the details of their life except that the dishes were dirty and that her brothers were hungry. It left her feeling unprepared for the world, and she vowed that she would share everything with her daughter and raise someone more astute than she. “I don’t understand the world or other people like you do, Qian Qian. All I understand is dishes."

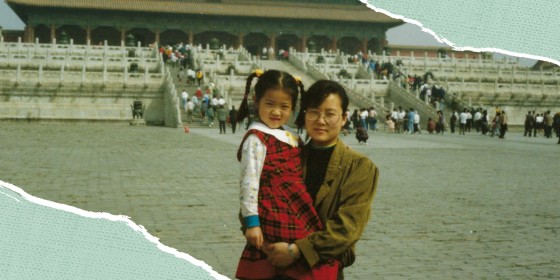

Before we left China, whenever my mother’s friends asked me what I wanted to be when I grew up, I replied, “I want to be Ma Ma,” referring to my deep desire to not just be any mother, but my mother — the magical woman who went from writing statistical textbooks to making mouthwatering dumplings to designing and sewing the most beautiful dresses for me, all in a single day. My mother, though, would always chastise me for my unchanging answer: “How shameful, Qian Qian! You should want to be something more than just a mother.”

She herself had learned to cook too early, she said. “That is my life, Qian Qian, not yours. You have bigger things to do.”

I remember later standing on my little step stool and watching her with an open mouth and bated breath as she chopped her way through a large onion, turning it into a collection of neat, identical cubes even though the blade scarcely seemed to move. I loved watching her cook, but she refused to teach me to make a single dish. She explained that if a woman knew how to cook, she was doomed to do it for others — to serve others — every day for the rest of her life. She herself had learned to cook too early, she said. “That is my life, Qian Qian, not yours. You have bigger things to do.”

My realization from these memories was this: My mother has spent my whole life warding off what she does not want for me, freeing me up for things she could never hope for herself. How natural, then, that when good things happen to me, she rejoices in the success of her efforts, and sees fit to continue her emotional labor, trading her worries for my happiness.

Today, when she responds to my good news with worry, I no longer see it as her trying to ruin my day. I do my best to shrug off my annoyance at the insistent negativity. It has taken me over three decades to get here, but now I know that it is just her way of telling me that it’s nothing I have to be concerned about, because she is already warding it off for me. And the best thing I can do in return is try to live that life she does not have: the one liberated from constant worry. The one that revels in the joy of good news without concern about having to earn it through the catastrophe soon to arrive. The one that trusts that blessings need no payback because they are already protected by my mother’s singular, devoted love, expressed in the only medium available to her.

This is Qian Julie Wang’s personal essay, “Worry: My Mother’s Talisman of Love.” Her book, "Beautiful Country," was the Read With Jenna book club pick for September 2021. For more information on the book club head to TODAY.com/ReadWithJenna.

To stay up to date on the latest book club news, subscribe to the Read With Jenna newsletter!

For more book recommendations, check out:

- Jenna Bush Hager selects 'impactful' memoir for September 2021 book club pick

- 'The Nightingale' and 14 other historical fiction books Read with Jenna fans love

- All of Jenna Bush Hager's book club picks

Subscribe to our Stuff We Love and One Great Find newsletters, and download our TODAY app to discover deals, shopping tips, budget-friendly product recommendations and more!