It’s a question that has loomed in Hollywood for nearly as long as film and television have been in existence: how to prevent child actors from being exploited?

Over the years, laws have been passed to protect children who act in TV shows, movies and commercials. Now, though, a new batch of young entertainers has emerged: the children of reality television stars and social media influencers who appear on-camera as their real-life selves.

In a recent Psychology Today essay with the headline “The ‘Reality’ of Kids on Television,” sociologist and author Hilary Levey Friedman argued there should be laws in place to protect the children who appear on reality TV and social media.

In her piece, Friedman, who teaches at Brown University, noted that child actors in California are protected in part by the Coogan Law (so named for the early child actor Jackie Coogan), which was passed in California in 1939.

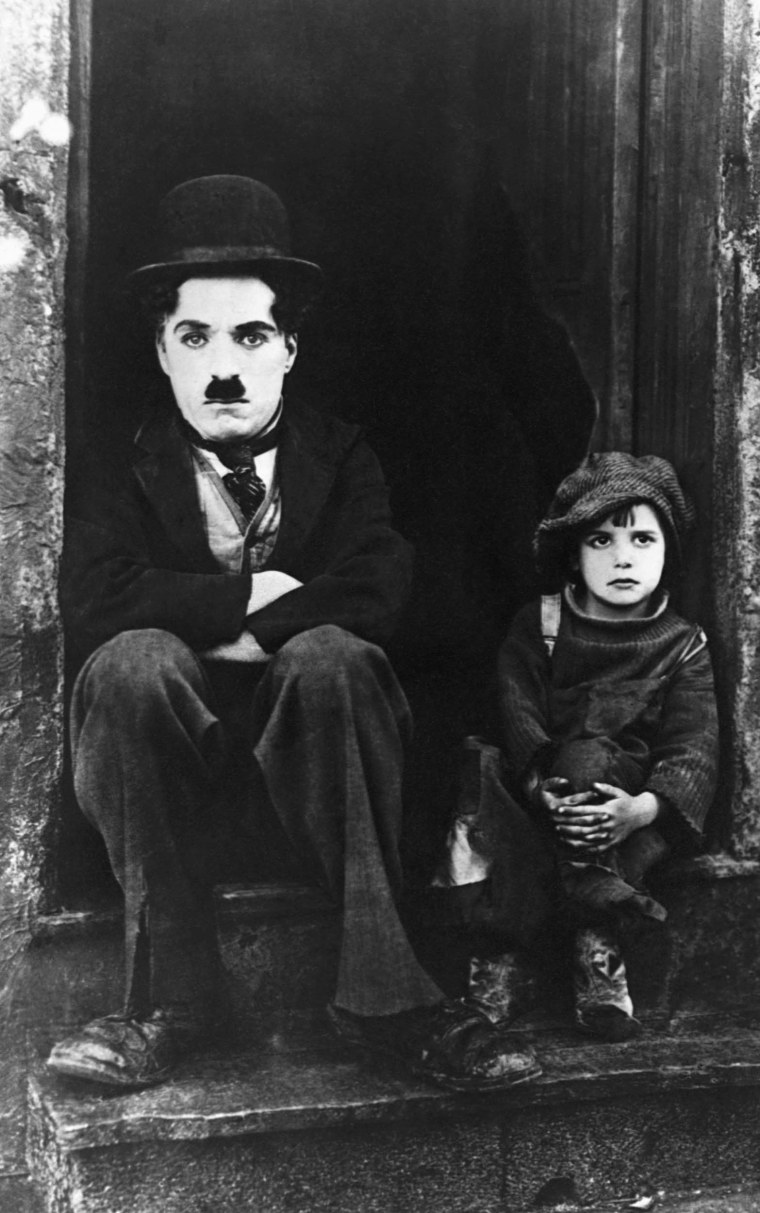

The Coogan Law came as a result of a lawsuit filed by the former child actor against his mother and his stepfather in 1938, according to Screen Actors Guild — American Federation of Television and Radio Artists. Upon turning 21, the child actor (who starred alongside Charlie Chaplin in the 1921 silent comedy “The Kid”) learned that his parents had squandered his childhood earnings.

Following decades of lobbying and adjustments, today’s Coogan Act requires contracts for child actors and performers to set aside part of their income to be put in a trust fund or account that can only be accessed once they’ve reached the age of 18.

Similar laws eventually were passed to protect child actors in other states, including New York, Illinois, Louisiana and New Mexico. After the performances of Jon and Kate Gosselin’s eight children became an issue in the reality show “Jon & Kate Plus 8,” the state of Pennsylvania passed a law that provided some protections for child reality stars.

Nevertheless, in most parts of the country, children “performing” on reality shows and on social media — including in ads that appear in their parents’ sponsored posts — remains a nebulous area, with many kids appearing without any protections. NBC News reported that “neither the Fair Labor Standards Act, a 1938 law addressing ‘excessive child labor,’ nor California’s Coogan Act, which protects child actors, have been updated to include child influencers.” According to the U.S. Department of Labor, 17 states do not regulate child entertainment at all.

“When you consider that children who appear on reality television shows deserve at least as much protection as other child performers, it is not difficult to go even further and argue that they deserve more protection because it is their own identities and their own lives being put on public display,” Friedman writes in her essay.

Related: Their children went viral. Now they wish they could wipe them from the internet

Sally Greenberg, executive director of the National Consumers League, agrees that more protections are needed.

“Reality TV is the Wild West,” Greenberg told TODAY in a statement. “State and federal laws must be enhanced to … ensure children are not exploited and abused. Work hours must be limited to ensure the child’s educational development isn’t impaired and child participants must have a portion of family proceeds placed into a trust fund for their future needs.”

Controversies emerge over kids’ appearances

In recent years, the issue of children appearing in reality TV shows, viral videos and paid social media posts has sparked criminal investigations and spats between celebrities online.

One recent public incident involves Hudson London Anstead, the 3-year-old son of HGTV “Flip or Flop” star Christina Hall and her ex-husband and fellow television personality, Ant Anstead. Since their divorce, the two have publicly battled for custody of their young child both in court and on Instagram.

In April 2022, Anstead reportedly filed papers in court taking exception with the way Hall had featured Hudson in sponsored posts on her Instagram account. Hall responded by saying that Hudson hadn’t appeared in an ad on her account since the issue was first raised with her in April, People reported.

In a post on Oct. 3, Hall wrote that she is so “mentally exhausted” from the situation that she decided to stop sharing Hudson on any social platform “until he is old enough to make this decision for himself.” She added that she had involved her young son in filming her reality shows so he could “participate in the fun activities/outings with our family/siblings” that happen while filming.

Friedman referenced Hudson in her Oct. 24 Psychology Today essay and argued for a modern-day “Hudson’s Law” to protect kids on reality TV and social media. This reference to Hudson in the essay prompted Hall to take to Instagram on Oct. 25 to decry the idea as “clickbait at its finest.”

“Hudson’s Law?! Really?” Hall wrote. “That is absurd. You don’t know anything about my household. Hudson is MY son. I’ve always protected him and always will.”

Hall added in her post that having her children film with her for “an hour (max) once every couple months” is “extremely different than scenarios when children are the main characters like in ... ‘Toddlers & Tiaras.’”

TODAY reached out to Hall for further comment but her representative declined. Her ex, Anstead, sent TODAY the following statement:

“I am proud that I stood up for our son at a time in his life when he had no voice. Hudson’s childhood is simply not for sale.”

What is the impact of being a child performer?

In an interview with TODAY, Friedman explained that she put her idea of “Hudson’s Law” in quotation marks in her essay to underline that “we need something like this.”

“(Hall and Anstead’s case) is just a very high-profile case right now,” Friedman said. “It’s an interesting case legally because here’s two parents. One has consented, and one does not want to consent, to their child’s participation in reality TV or in paid ads. And so that’s an interesting legal question. How is family law going to make sense of that?”

Related: Why I put my family — and my son’s autism — on reality TV

Fran Walfish, a child, couple and family psychotherapist based in Los Angeles, told TODAY that she has worked with both child actors and child reality television personalities. She stressed that there is a need for laws that protect child reality television personalities specifically.

“I do agree that protecting identities is crucial, and it is more important than protecting a role that someone is pretending and playing for a fantasy and imaginary role,” Walfish said.

“Children developmentally are going through critical phases of psychological development and the core internal issue is developing a sense of self,” she explained. “That does not just mean self-esteem. It’s a sense of, ‘Who am I in the world? Who am I in relationship to my family and to other people?’ And it includes a value system (and) ethics.”

Friedman noted that the intersection of child labor laws and children featured in reality TV and paid social media appearances is more timely than ever.

“Lots of parents share their kids on social media,” Friedman said. “As kids get older, they’re like, ‘I don’t want you to share that even to, you know, 30 family and friends or whatever, because that’s my life.’ So that is actually an issue ... but it’s quite different from it being tied to someone’s being compensated. ...

“That’s a form of child labor. There’s money involved in transaction, and that’s how we define work.”

Walfish’s message to parents is to think deeply about how and where they decide to spotlight their children.

“Really think twice if you’re a parent and you’ve got a child who is endowed with talent,” she advised. “Nurture it with lessons and classes, and tell your child, ‘When you’re over 18, you get to make that decision and choice’” about social media.

Related video: