As children of the mid-1960s to 1980, Generation X came into a world being shaped by radicalization. Some were born in the counter-culture decade of the '60s, others, the economic upheavals of the '70s — an era defined by scenes of protest, celebration, political strife.

But their births were also in synchronization with the Gay Liberation Movement, which exploded thanks to the strength of previous generations.

According to the National Archives, federal employers forced thousands of employees out of their jobs between the late 1940s and through the 1960s due to their sexual identities. Galvanized by the wave of persecution, Gen X grew up as activists threw their weight behind marches, combatting workplace discrimination, police intimidation and violence all so they could live their lives out in the open.

Like the first waves of feminism, the efforts of Black, Latino and transgender activists played a large part in some of the most defining moments of this era — though their livelihood and rights remain threatened.

The pages of American history know moments like the Stonewall Riots of 1969 well, but often lose sight of the efforts that carried its momentum, including the awareness raised by the 1965 police raid on California Hall’s New Year’s Day Ball and the 1966 Compton’s Cafeteria Riot. All the while, leaders like Stormé DeLarverie, Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera brought hope and awareness in the face of the blood and brutality that erupted.

The community also pushed forward to make groundbreaking milestones.

- In 1972, Madeline Davis became the first open lesbian delegate to take part in a major U.S. convention after she was elected to the Democratic National Convention for New York’s 37th Congressional district.

- In 1977, Harvey Milk became the first openly gay man to be elected to U.S. public office when he became a member of the San Francisco Board of Supervisors. Nearly 10 months after he was sworn in he was assassinated.

- Towards the tail end of Gen Xers being born, Stephen Lachs became the first openly gay judge in the world when he was appointed to the Los Angeles Superior Court in 1979.

Now, in 2023, members of Generation X look back on their own defining eras, and the moments in which their identities were shared with and expressed to the world. Shrouded in acceptance and relief and, in some cases, anguish and regret, here are the moments they hold in their hearts.

Dominique Jackson: ‘It took 30 years for my mother to actually see me’

Coming-out in the ‘90s was a “disaster” for Dominique Jackson. In 1993, she told her family that she was trans after she yearned for a sense of freedom at home.

“I knew I was going to lose a lot,” she tells TODAY.com. “I was going to lose the ability to continue my education. I was going to lose my safe space, which was my home. And it was terrifying.”

I couldn’t explain to them that I was trans. I didn’t have the vocabulary for it back then, so all I could say was that I was different and they assumed it was gay.

Dominique Jackson

Jackson, who was 18 years old at the time, remembered being attacked at Morgan State University in Baltimore, Maryland. Although her family thought that she was “gay,” Jackson knew that wasn’t how she identified.

“I couldn’t explain to them that I was trans. I didn’t have the vocabulary for it back then, so all I could say was that I was different and they assumed it was gay,” she says. “And so I left my house and had to live in an apartment with about six other people. The amazing part about that is that’s how I found ballroom and it was those people from ballroom who took me in.”

The “Pose” star says the trauma of coming out to her family lasted for 30 years. It wasn’t until “Pose” debuted in 2018 that she decided to call up her mom and make amends.

While it was hard, Jackson says her mother finally came to an understanding of who she was.

“She finally was like, ‘Listen, I’ve always loved you and I do love you, but, now I know I have to respect you and I will try.’ So it took 30 years for my mother to actually see me and she still hasn’t seen me fully, but she’s still seen me.”

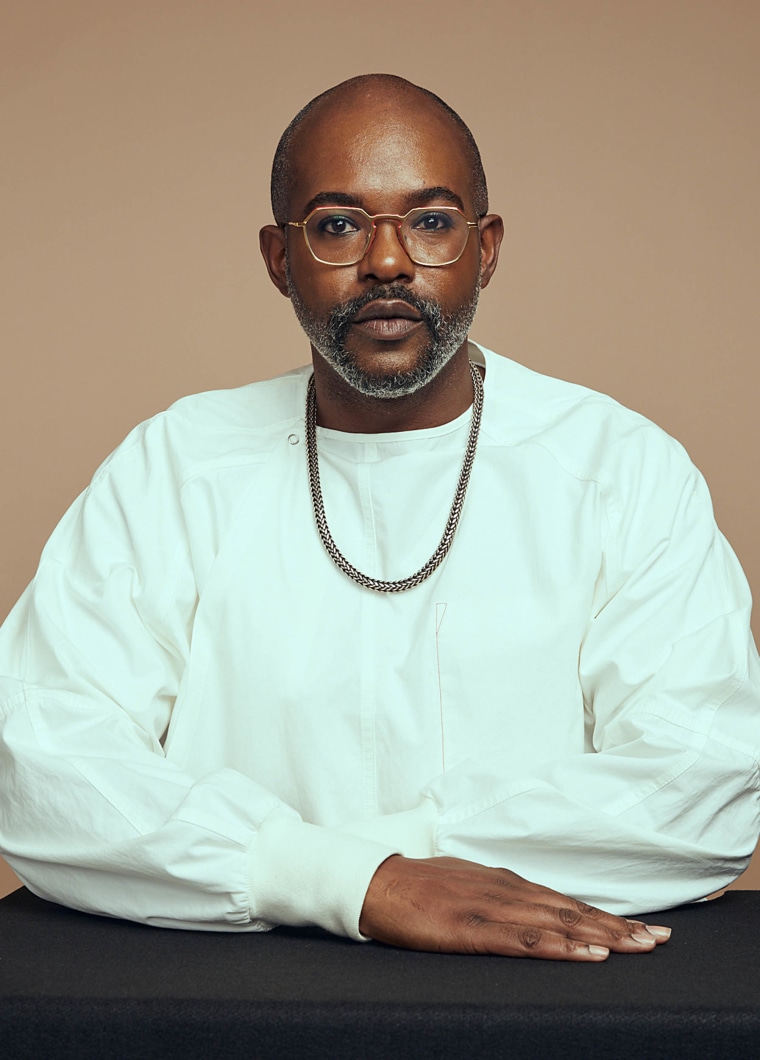

James Earl Hardy: ‘We’re not coming-out, we’re letting people in’

James Earl Hardy, 57, does not believe in coming-out. He believes in inviting the right people in.

Born in 1966, it took Hardy, the “B-Boy Blues” screenwriter and executive producer, nearly 30 years to open up about his sexuality to his parents.

“I suppose I officially ‘came out’ when ‘B-Boy Blues’ was released (in 1994),” he says of his novel that later became a series of seven books and a movie on BET+. “I gave them both a copy of the book.”

Hardy's novel is a rom-com featuring two male leads who fall in love. The story is not based on Hardy’s life, he says, but both he, his parents and their family members read it as his coming-out story.

“Most of them were not surprised,” he recalls of his family's reaction to learning he was gay. “They were relieved that I felt comfortable enough to finally just say it.”

We have evolved somewhat over the past 30 years when it comes to LGBTQ+, same gender loving rights, so that gives us more ownership.

James Earl Hardy

Hardy recognizes how sharing this part of his identity with his family — and how they responded — is a privilege inaccessible to some.

“I’m really blessed in that regard, as I have parents who have always supported me,” he says. “I had to learn that not everybody is worthy of that. Sometimes we have to be very careful of who we extend that privilege to.”

For that reason, Hardy says the phrase “coming-out” has been reframed over the years.

“Today, I guess people don’t say so much that they’re coming-out, but they’re letting people in,” he says. “We have evolved somewhat over the past 30 years when it comes to LGBTQ+, same gender loving rights, so that gives us more ownership.”

“We’re not so much coming-out to you, our families, friends, the world, but we’re allowing you to come in,” he explains. “Experience what our lives are like … realizing that they’re really not that much different from yours.”

Elegance Bratton: ‘I discovered home’

Before Elegance Bratton became a Golden Globe nominated filmmaker, he was a 16-year-old kid seated on a rattling PATH train with his life packed into three gallon trash bags.

His name was Elegance then, too, and he tells to TODAY.com that his mother settled on the name soon after she gave birth to him when she was also just 16 years old.

“You know, when the babies get smacked and they start crying?” he asks. “She said when I got smacked, I gasped and I looked back at her and she thought it was the most elegant thing she’d ever seen.”

Ironically, the same woman who gave him the name that led some to assume that he was gay, was the same one who forced him out of her house when she learned that he was interested in boys.

“My coming-out story begins with a boy calling me — that I’ve met out on a night in New York ... (on) my family line,” Bratton explains. “I don’t know what it was about that call but my mother knew right away that this boy calling me was very different from my other friends calling me.”

I heard these Black gay men and I assumed they were Black and gay because they were just so loud and fanboying and proud. I followed them because I was like, ‘Wherever they can go and be that gay, I need to go there.’

Elegance Bratton

“The Inspection” director remembers quickly packing all that his mother would allow him to take with him into five, three gallon trash bags including his clothes and a beloved copy of “Invisible Man.”

“I talked my way onto the train, I didn’t even have money to ride the train,” he says, recalling that he didn’t really know exactly where he was going to stop. Eventually, he ended up in New York City, where he says he saw a group of men on the train.

“I heard these Black gay men and I assumed they were Black and gay because they were just so loud and fanboying and proud,” he says. “I followed them because I was like, ‘Wherever they can go and be that gay, I need to go there.’”

Incidentally, they got off on Christopher Street, the location of the Stonewall Inn, a now National Historic Landmark and the site of the 1969 riots that helped launched the gay rights movement.

“I just got there and got off the train and it was, in a way, kind of like a dream come true,” he explains. “I discovered home. People were eager, it seemed, for my arrival, even though they didn’t know me.”

“Magical” is the word that Bratton uses to describe the rest of the evening. With the glimmer of disco balls and the pulse of various nightclubs in the background, he had his first kiss and eventually watched the sun rise.

“Everything I’d been waiting to happen, happened that night,” he says, adding that the magic soon wore off when the reality of his future sunk in.

“You have to go to bed and there’s nowhere to sleep,” he notes.

Bratton says he eventually returned to his mother’s home “a few days later, and swore up and down (that) I was not gay.”

“And so (began) the cycle of the next 10 years of my life being homeless again,” he says.

But Bratton's story doesn't end there. At the age of 25 the director joined the Marine Corps, then enrolled in college. Today, he holds two degrees: a Bachelor of Arts from Columbia University and a Master of Fine Arts from New York University. In 2019, he directed “Pier Kids” a documentary about three LGBTQ homeless youths in New York City. In 2022, his film “The Inspection” debuted to critical acclaim. Out and proud, he lives in Los Angeles with his longtime partner.

TODAY.com is exploring what coming out means and how it’s changed from the perspective of members of the LGBTQ+ community across generations. In addition to the Gen X, read what Baby Boomers, millennials and Gen Z have to say.