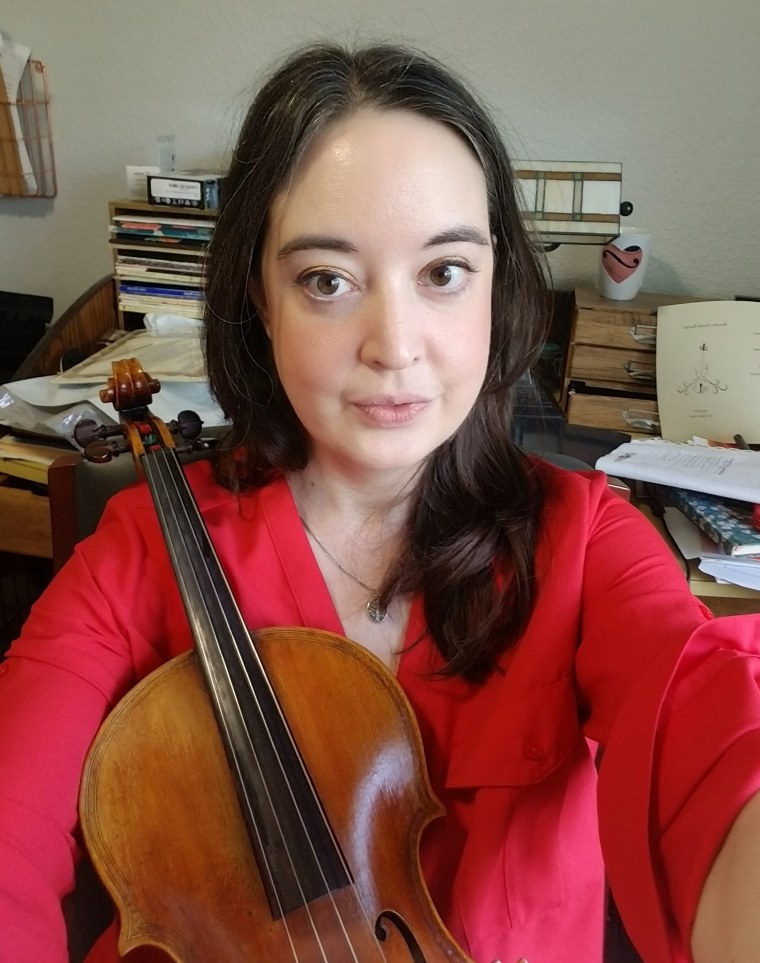

I was halfway through a large bag of chocolate-covered espresso beans the moment I first became aware I had a life-threatening illness. Like I did most evenings, I’d driven to the music building on campus, picked up some snacks and found an empty room to practice my viola. I was in my first semester of graduate school at the University of Hartford, studying music performance. I was excited about my classes, excited to make new friends and excited about my future. But as I munched on the espresso beans in between learning the notes to a new Bach suite, I suddenly realized I felt different than I usually did. I felt clear-headed and alert, able to concentrate on my music and learn quickly. Another disturbing realization immediately followed: I hadn’t felt clear-headed, alert, or anything but exhausted and strangely mentally foggy for several months. At 21 years old, I had no way of knowing the rocky path that lay ahead — the endless doctors’ appointments and blood draws, the harrowing months in which my body and brain felt like a stranger’s. But in that moment, I knew something was horribly wrong with me.

Over the course of the next year, I would schedule doctor’s appointment after doctor’s appointment in search of answers. During that time, I would grow steadily sicker. My hair would fall out in chunks. I would become too exhausted to practice my viola, then so exhausted I could barely walk down the hallway of the music building to my classes. The brain fog would intensify until I was incapable of even following the directions on a packet of instant oatmeal, then eventually spiral into psychosis. By the time I was finally diagnosed with a common and well-known autoimmune disease, lupus, I had been walking, driving and attending class with severe inflammation in my brain, called lupus cerebritis, for over a year.

An estimated 1.5 million Americans live with lupus, and 90% of lupus patients are women, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sometimes called “the great pretender,” lupus is capable of mimicking other diseases, like multiple sclerosis or arthritis. The Mayo Clinic website states that most lupus patients experience fatigue, joint pain and a butterfly-shaped rash across their cheeks and nose. I suspect my lack of joint pain or facial rashes contributed to my case of lupus being more difficult to diagnose. Because lupus is an invisible illness, I never looked sick, even when I felt like I was dying.

The day after that epiphany in the music building I scheduled an appointment with the first primary care physician I googled that my insurance covered. I sat in his office and described the fatigue that pushed me back into my bed like a weight each morning, then clung to me throughout the day no matter how much I slept. I mentioned the alarmingly large clumps of hair that came off in my hair brush and clogged my shower drain each week. I told him about the eerie mental fog that made it impossible to concentrate.

Naively, I had expected the doctor to prescribe a regimen of antibiotics or some other pills that would immediately return my body to its usual healthy, energetic state. At the very least, I’d hoped that the doctor would listen to me, ask about my family medical history and run some tests. Instead, he interrupted me.

“You’re homesick and probably depressed,” he said. He looked bored, as if he couldn’t be bothered to take time away from patients with real problems to listen to a young woman complain about not being able to concentrate on her schoolwork.

I left the doctor’s office not with a prescription or a blood test panel, but with a psychiatrist’s name scribbled onto a scrap of paper that the receptionist forcibly pushed into my hand.

My exhaustion and brain fog didn’t feel like homesickness. It felt like my body was shutting down. I left the doctor’s office not with a prescription or a blood test panel, but with a psychiatrist’s name scribbled onto a scrap of paper that the receptionist forcibly pushed into my hand.

Despite the prevalence of lupus among American women, most lupus patients spend an average of nearly six years searching for a diagnosis, according to one 2019 survey. Many lupus patients seeking a diagnosis experience medical gaslighting: doctors who don’t take their patients’ pain seriously or who blame their symptoms on unrelated factors, like their mental health or their weight. As I soon found out, lupus symptoms can become life-threatening when left undiagnosed and untreated.

Over the next few months, my exhaustion grew more severe. Even after sleeping 10 hours a night, I could barely stumble out of bed each morning. The fatigue was so extreme at times that I hallucinated the walls spinning around me. Then one day as I was standing in the checkout line at CVS, I noticed that the faces on the fashion magazines were glaring at me. Anxiety that my classmates all secretly hated me gripped me. I later learned that my disease, left unchecked, had developed into psychosis, a mental disorder that twisted the reality of the world around me like a funhouse mirror. For months, my emotions vacillated wildly from depression to giddiness with no warning or reason. I whispered and stared at the floor in conversations with my classmates, lost in the delusion that they all despised me.

I was misdiagnosed with depression, bipolar disorder, Lyme disease, thyroid disease and mono. I had more pregnancy tests foisted on me than I could count, including one while I was on my period. Doctor after doctor failed to take my symptoms seriously. “We’ll just wait a few months and see if this clears up,” several told me. The thought sliced through the fog in my mind: I was dying from lack of medical care in a developed country where resources were not scarce, all because I couldn’t get anyone to listen to me.

I learned to comb through Healthgrades ratings and ask my professors if they could recommend any doctors before making new appointments. The seventh doctor I saw never once glanced at the clock as I talked. Her brow furrowed in concentration as I described my symptoms. She asked questions. She ran tests. As my disappointment in the medical industry grew, Dr. S’s persistence reminded me that there were doctors who chose their profession for the same reason I later chose to become a teacher: They genuinely wanted to help people, and they wouldn’t let a complex problem stop them from doing so. Dr. S finally diagnosed me with lupus about a year and six months after that evening in the music building when I first realized I was sick. I didn’t feel despair at being told I had a lifelong serious chronic condition. Instead, relief expanded in my chest like a balloon. I hadn’t imagined my symptoms. I wasn’t crazy; I really was physically ill.

I didn’t feel despair at being told I had a lifelong serious chronic condition. Instead, relief expanded in my chest like a balloon. I hadn’t imagined my symptoms. I wasn’t crazy; I really was physically ill.

For many people with serious illnesses, a diagnosis is a pathway to an improved quality of life. An official diagnosis leads to medical treatment, doctors who see their symptoms as credible, and the chance to connect with a community of other patients for support. I had begun reading blogs and comment threads written by other people with similar symptoms to mine during the year I spent searching for answers. After my diagnosis, I started following more blogs about lupus. Learning about my disease helped me manage my symptoms and understand how my medication worked. The brain fog, psychosis and fatigue slowly faded away after a few months of medical treatment, but I continued to read and learn. Managing my illness would be a lifelong goal.

I didn’t speak openly about my disease for many years. I worried that my colleagues wouldn’t want to work with someone who still occasionally struggled with fatigue and brain fog, and that no parents would want their children to study with someone who had once been psychotic.

In the months I spent visiting doctors and trying to find answers, I had found comfort and solace in the stories that other chronic illness patients shared online. One day years after that evening in which I had first realized I was sick, I had another realization: In not sharing my experience with lupus, I was contributing to the same lack of awareness that had made me feel so isolated during my search for a diagnosis. Writing about my experience with lupus healed some of the trauma of that year I spent searching for answers and helped me fish a glimmer of meaning out of the pain I went through. I hope that speaking out about the darkest point in my life will shine a light for others navigating the same treacherous path. We all carry our personal stories into the exam room, and the doctors who listen to these stories make all the difference.

Do you have a personal essay to share with TODAY? Please send your ideas to TODAYEssays@nbcuni.com.