Jenna Bush Hager says her next book club pick is about “doing the unthinkable.” She told TODAY, “I don’t think I’ve ever read a memoir which captivated me in so many ways.”

September’s Read With Jenna pick is “Solito,” a memoir by Javier Zamora. “It was a beautiful book about family, those that we have and those that we make, and the little family that they made on their journey, which was almost sort of "Iliad"-esque. An epic journey to their loved ones, because they had no choice,” Jenna said.

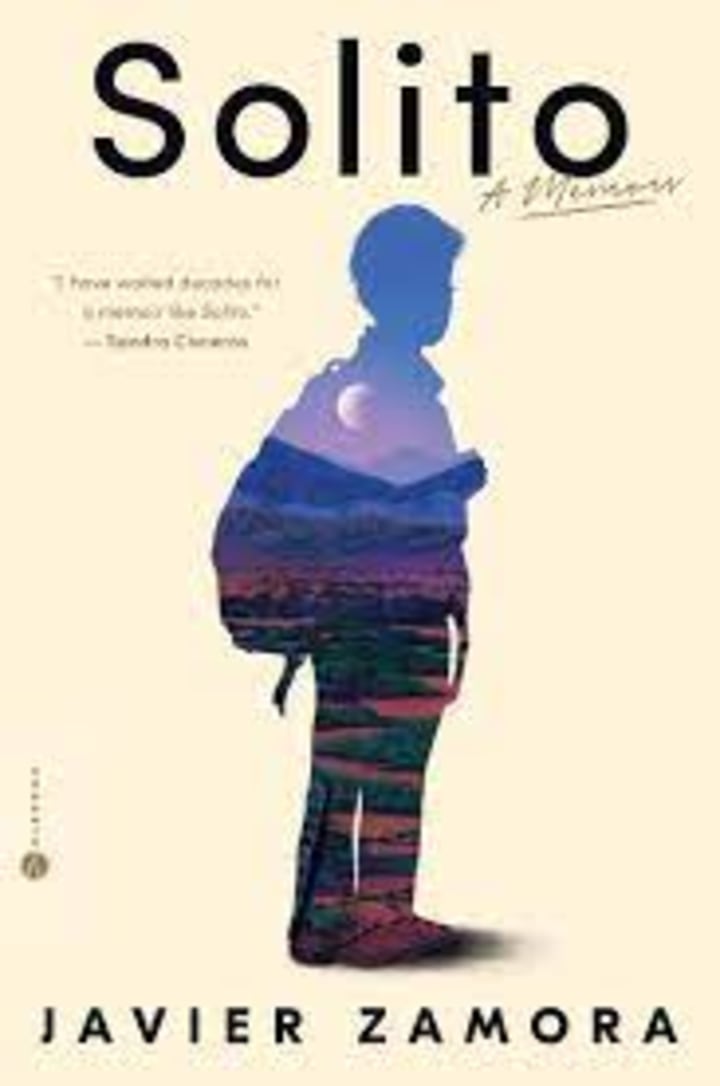

"Solito" by Javier Zamora

When Zamora was 9 years old, he left his home in El Salvador in an attempt to join his parents in the United States. Zamora’s mom had made the same 3,000-mile trek in about two weeks. Zamora was told his trip would take the same amount of time, accompanied by the same "coyote," slang for someone smuggles immigrants across a border — but he ended up being away for two months, traveling with a group of strangers that he said became like a family.

“It wasn't supposed to be like this,” Zamora told TODAY. “(My parents) were using the same guy that brought my mom here safely and very quickly. Then things went completely wrong.”

Zamora previously wrote about his experience crossing the border in a collection of poetry, "Unaccompanied," which he began writing his senior year of high school. “I started writing because my story from a Central American written by a Central American and immigrant story did not exist,” Zamora told TODAY.

This memoir fills in the details he couldn’t previously share in the poetry collection. “Poetry was as far as I wanted to dig into this story. I couldn't emotionally go deeper. I couldn't fill the page yet,” he said.

Zamora said writing prose required “privilege” he didn’t have access to as a teenager. For example, getting a green card allowed him to return to El Salvador and move to Tucson and research the place he immigrated through. “Those are things I couldn’t have done without papers,” he said.

He also credited his work with his therapist, who is a child immigrant herself, with being able to access these memories. “The cards aligned for me to really open the door and face the kid — me,” he said. "My 9-year-old self."

“Solito” is told from the perspective of that 9-year-old, with the limited perspective and sense of baffled bewilderment and loneliness preserved. Zamora initially began writing the book in the past tense. Then, he said, when he got to the “boat scene” — in which he recounted the disorienting and harrowing time spent on a boat in the Pacific — he snapped into writing in the present tense, accessing the voice of his younger self.

From there, he said, all of the chapters were written in chronological order. For Zamora, recounting those two months was a visceral experience. As the story unfolded, Zamora would have frequent nightmares, which he would attempt to write down in the morning. “I would cry, my body would ache weirdly on my left side, whenever I remembered something. At one point, I realized the left side was the one I was getting pulled by (on my journey),” he said. Zamora said meditation, therapy and reiki allowed him to heal along the way.

Jenna hopes the book has an impact on readers, especially as stories about migrants continue to populate headlines. “I hope that this book will be an instrument of change and will be a start to a conversation about what so many families sacrifice,” she said.

Zamora also hopes the book is a conversation starter among immigrants, too. “I hope that my story makes it OK for us immigrants to begin to look at our trauma and look at it and with wanting and knowing that there is healing,” he said.

While reading, Jenna thought about her own daughter Mila Hager, who is 9 — the same age Zamora was when he left his relatives and traveled north. “I couldn't help but think about this little boy all alone, doing the unthinkable. That little boy was so courageous," she said.

For Zamora, that type of reaction is the point. “It is harder to ignore a child who's telling you that story than it is to ignore a teenager and an adult,” he said.

“What the 9-year-old kid that's inside of me always wanted to do was to be seen. And you can't ignore a book — I am literally taking up space in the world. It's harder for anybody to ignore me now. That’s what the 9-year-old boy was searching for all along,” he said.