Laurie Bertram Roberts remembers the emotion that consumed her when, as a 19-year-old single mom of two, she needed an abortion.

Fear.

She was only three months postpartum and recovering from a C-section when she found out she was pregnant again.

She's now 45, but vividly remembers desperately searching for the nearest clinic, poring over every weathered phonebook she could find as her newborn slept in her arms.

The memory of learning that the nearest clinic was an hour away from her mother's Mississippi home, where Roberts lived, still leaves a pit in her stomach.

She remembers frantically trying to scrounge up enough money to pay for the procedure and travel.

By the time she got to the clinic, Roberts had passed Mississippi's 15-week gestational limit that existed at the time.

“My check came one day too late,” Roberts tells TODAY.com. “They literally turned me away.”

She could no longer have a legal abortion.

“It wasn’t even a gut-punch," she remembers. "It felt like someone broke me."

She drove back home, alone.

“I cried the whole ride. Oh god, I’m about to cry now,” she says, breaking down. “I haven’t thought about that drive in 25 years."

“It was just so hard,” she adds, sobbing. “I didn’t know what I was going to do.”

'People ... assume you don't love your child'

When Roberts got pregnant in 1997, abortion was illegal in Mississippi after 15 weeks. Now abortion is totally banned in the state, with limited exceptions.

In the year since a Supreme Court decision overturned Roe v Wade, 23 additional states have banned or severely restricted abortion care.

I love my child to the ends of the earth. That doesn’t make what happened any less unfair."

Laurie Bertram Roberts

“People want to attack you and assume you don’t love your child,” says Roberts, who is sharing her story only with permission and encouragement from her daughter, who is now a young adult.

“How dare you? I love my child to the ends of the earth. That doesn’t make what happened any less unfair.”

Twenty-eight million women and girls of reproductive age in the U.S. now live in a state where it's difficult or impossible to have an abortion.

For many of them, the loss of abortion rights has left them in a place Roberts knows all too well: With a baby they weren't ready to care for.

"Research suggests that tens of thousands of people are being forced to carry their pregnancy to term," Noreen Farrell, executive director of Equal Rights Advocates, a non-profit gender justice organization that supports abortion rights, tells TODAY.com.

'I didn’t want to leave my kids without a mom'

In 1997, Roberts was living with her mom and surviving off tips as a service industry worker. She barely had enough money to afford a pregnancy test.

"I was also facing the prospect of having my third C-section in five years," she says. "My doctor explicitly told me: 'You could die.'

"I didn't want to leave my kids without a mom."

Her fear of dying in childbirth was not unfounded. In 1997, Mississipi had one of the highest maternal mortality rates in the country, and the state continues to be one of the most dangerous for mothers giving birth.

Experts who study demographics and public health say forcing people to carry unwanted pregnancies will cause an increase in the U.S. maternal mortality rate — already the highest of any developed nation, according the the CDC.

“It’s estimated that US maternal deaths will increase by 24%,” Farrell says. “For Black women, deaths could rise by as much as 39%.”

After she was denied an abortion, Roberts says she was thrown into a "mental health crisis," living two lives — she was doing what a pregnant person is "supposed to do" to ensure a fetus is healthy, while hoping and sometimes trying to end her pregnancy on her own.

“I had this dual reality that I was living in, where was going to my prenatal appointments but I was also throwing myself down the stairs, ” Roberts said. "I rode a bunch of rides at the fair that you can’t ride if you’re pregnant ... it didn’t do anything.”

Roberts says she had been “anti-choice my whole life,” so being denied abortion care was a shock.

“I prayed and cried and prayed and cried (in order) to be OK with my decision,” she says. “Getting the money together ... only to be told that my last hope for making the best choice for my family was gone? I was so worried for my kids.”

‘I don’t have a flowery story for you’

Before Roberts found out she was pregnant, she had obtained her GED and started taking college courses. She had a plan for her life.

As her pregnancy progressed, she dropped out of school in order to look for jobs to support her two children.

Then, at seven months, she was put on bedrest and could no longer work.

Behind on bills, she ended up homeless and lived out of a hotel room for over a year.

“It makes the ground underneath you shift,” Roberts said of being forced to stay pregnant. “It makes you choose different things ... even the abusive relationship I chose to stay in ... I needed a house. I needed stability ... I was a sex worker. I was a stripper."

Roberts wasn't financially able to go back to school until she was 25. It took her longer, she says, to get out of abusive relationships that gave her some semblance of financial security.

“Sometimes you have to work with the options that you have,” she adds. “I don’t have a flowery story for you.”

According to a study of 1,000 women in 21 states over 10 years conducted by the University of California, San Francisco, when a person is denied an abortion they’re more likely to live in poverty, have a higher risk of experiencing adverse mental health conditions, and are more likely to stay in unhealthy relationships.

“We know that the economic consequences will have impacts for generations,” Farrell says.

“It’s not that I didn’t want her, there’s just a difference between not wanting a child and not wanting a child at that moment."

Laurie Bertram Roberts

‘I just didn’t want or deserve the trauma’

Today, Roberts works as a doula and serves as the executive director of Mississippi Reproductive Freedom Fund, an organization that provides contraception and helps people access abortion care out of state.

After she was denied an abortion, she says it took her years to work toward her educational and professional goals, but it also gave her a purpose: She didn't want what happened to her to happen to anyone else, including her own children.

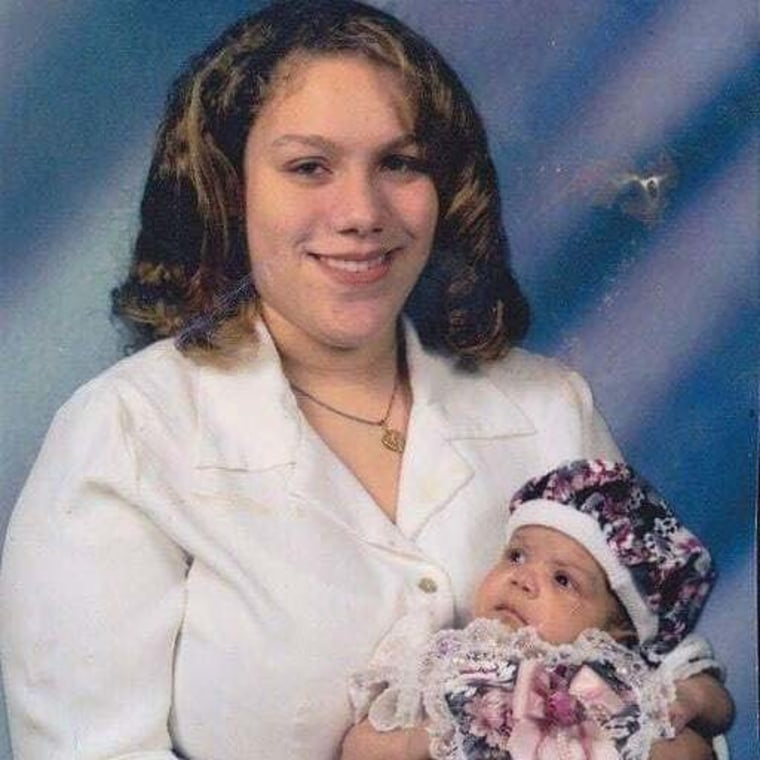

At 19, Roberts gave birth to her third child — a healthy baby girl.

Her daughter is now an adult, who knows her origin story.

“She’s had an abortion, so she understands why I felt the way I felt,” Roberts says. “It’s not that I didn’t want her, there’s just a difference between not wanting a child and not wanting a child at that moment."

“I just didn’t want or deserve the trauma," Roberts adds. "I deserved to be able to choose to have my child when it was safe and right for me.”