As Father's Day approaches, Michelle Obama is taking time to remember the special man who taught her plenty about life but also knew when it was time to have fun — her dad.

The former first lady lost her father, Fraser Robinson III, when he died at 55 in 1991, but she still has vivid memories of family vacations when they left their native Chicago behind and enjoyed the sunshine.

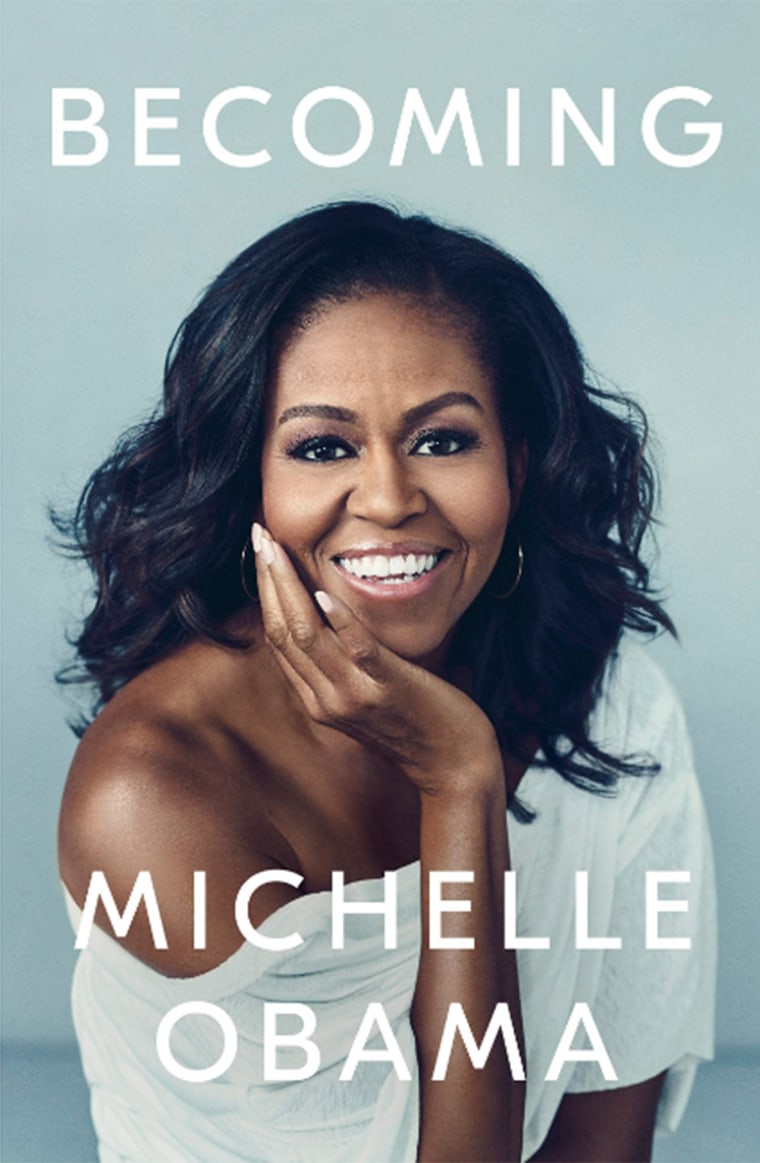

She also writes about his positive influence in her bestselling memoir, "Becoming," which was released in November and is excerpted below.

In remembering good times with her father, Obama shared a rare childhood photo with TODAY and the context behind it.

"Some of my fondest memories as a young girl were at a place called Dukes Happy Holiday resort in Michigan,'' she told TODAY. "For a city girl, it was full of open spaces to run and play games and an outdoor pool to jump and splash and practice my flutter kicks."

"When I think of those vacations, especially around this time of year, my thoughts naturally return to my father, who spent much of his life in a few-mile radius on the South Side of Chicago. Seeing him smile and kick back at this modest resort, though, gave me another angle on him — not a complete new picture entirely, but at least a fuller perspective on the man and what he carried with him."

Robinson worked in a water filtration plant for the city of Chicago, teaching a young Michelle about hard work and perseverance. He lived with multiple sclerosis, an unpredictable disease that can cause a variety of symptoms, from mobility and walking issues to numbness and speech difficulties, according to the Multiple Sclerosis Association of America.

In this excerpt from "Becoming," she writes about the lessons her father taught her, his life with MS, the frank conversations he had with her and her brother, and some fun family times they spent together:

"My Dad's Buick continued to be our shelter, our window to the world. We took it out on Sundays and summer evenings, cruising for no reason but the fact that we could. Sometimes we’d end up in a neighborhood to the south, an area known as Pill Hill due to an apparently large number of African American doctors living there. It was one of the prettier, more affluent parts of the South Side, where people kept two cars in the driveway and had abundant beds of flowers blooming along their walkways.

My father viewed rich people with a shade of suspicion. He didn’t like people who were uppity and had mixed feelings about home ownership in general. There was a short period when he and my mom considered buying a home for sale not far from Robbie’s house, driving over one day to inspect the place with a real estate agent, but ultimately deciding against it. At the time, I’d been all for it. In my mind, I thought it would mean something if my family could live in a place with more than one floor. But my father was innately cautious, aware of the trade-offs, under- standing the need to maintain some savings for a rainy day. "You never want to end up house poor," he’d tell us, explaining how some people handed over their savings and borrowed too much, ending up with a nice home but no freedom at all.

My parents talked to us like we were adults. They didn’t lecture, but rather indulged every question we asked, no matter how juvenile. They never hurried a discussion for the sake of convenience. Our talks could go on for hours, often because Craig and I took every opportunity to grill my parents about things we didn’t understand. When we were little, we’d ask, “Why do people go to the bathroom?” or “Why do you need a job?” and then blitz them with follow-ups. One of my early Socratic victories came from a question driven by self-interest: “Why do we have to eat eggs for breakfast?” Which led to a discussion about the necessity of protein, which led me to ask why peanut butter couldn’t count as protein, which eventually, after more debate, led to my mother revising her stance on eggs, which I had never liked to eat in the first place. For the next nine years, knowing that I’d earned it, I made myself a fat peanut butter and jelly sandwich for breakfast each morning and consumed not a single egg.

As we grew, we spoke more about drugs and sex and life choices, about race and inequality and politics. My parents didn’t expect us to be saints. My father, I remember, made a point of saying that sex was and should be fun. They also never sugarcoated what they took to be the harder truths about life. Craig, for example, got a new bike one summer and rode it east to Lake Michigan, to the paved pathway along Rainbow Beach, where you could feel the breeze off the water. He’d been promptly picked up by a police officer who accused him of stealing it, unwilling to accept that a young black boy would have come across a new bike in an honest way. (The officer, an African American man himself, ultimately got a brutal tongue-lashing from my mother, who made him apologize to Craig.) What had happened, my parents told us, was unjust but also unfortunately common. The color of our skin made us vulnerable. It was a thing we’d always have to navigate.

My father’s habit of driving us through Pill Hill was a bit of an aspirational exercise, I would guess, a chance to show us what a good education could yield. My parents had spent almost their entire lives living within a couple of square miles in Chicago, but they had no illusions that Craig and I would do the same. Before they were married, both of them had briefly attended community colleges, but each had abandoned the exercise long before getting a degree. My mother had been studying to become a teacher but realized she’d rather work as a secretary. My father had simply run out of money to pay tuition, joining the Army instead. He’d had no one in his family to talk him into returning to school, no model of what that sort of life looked like. Instead, he served two years moving between different military bases. If finishing college and becoming an artist had been a dream for my father, he quickly redirected his hopes, using his wages to help pay for his younger brother’s degree in architecture instead.

Now in his late thirties, my dad was focused on saving for us kids. Our family was never going to be house poor, because we weren’t going to own a house. My father operated from a practical place, sensing that resources were limited and maybe so, too, was time. When he wasn’t driving, he now used a cane to get around. Before I finished elementary school, that cane would become a crutch and soon after that two crutches. Whatever was eroding inside my father, withering his muscles and stripping his nerves, he viewed it as his own private challenge, as something to silently withstand.

As a family, we sustained ourselves with humble luxuries. When Craig and I got our report cards at school, our parents celebrated by ordering in a pizza from Italian Fiesta, our favorite place. During hot weather, we’d buy hand-packed ice cream - a pint each of chocolate, butter pecan, and black cherry - and make it last for days. Every year for the Air and Water Show, we packed a picnic and drove north along Lake Michigan to the fenced-off peninsula where my father’s water filtration plant was located. It was one of the few times a year when employee families were allowed through the gates and onto a grassy lawn overlooking the lake, where the view of fighter jets swooping in formation over the water rivaled that of any penthouse on Lake Shore Drive.

Each July, my dad would take a week off from his job tending boilers at the plant, and we’d pile into the Buick with an aunt and a couple of cousins, seven of us in that two-door for hours, taking the Skyway out of Chicago, skirting the south end of Lake Michigan, and driving until we landed in White Cloud, Michigan, at a place called Dukes Happy Holiday Resort. It had a game room, a vending machine that sold glass bottles of pop, and most important to us, a big outdoor swimming pool. We rented a cabin with a kitchenette and passed our days jumping in and out of the water.

My parents barbecued, smoked cigarettes, and played cards with my aunt, but my father also took long breaks to join us kids in the pool. He was handsome, my dad, with a mustache that tipped down the sides of his lips like a scythe. His chest and arms were thick and roped with muscle, testament to the athlete he’d once been. During those long afternoons in the pool, he paddled and laughed and tossed our small bodies into the air, his diminished legs suddenly less of a liability.

(Adapted from Becoming by Copyright © 2018 by Michelle Obama (Crown Publishing, an imprint of Penguin Random House)