We have all heard the math about healing after a romantic breakup. Half the length of the relationship should mend you right up, they say. If you were together for four years, you need to be ready to hurt for about two. Only two years of togetherness? No worries, then: Twelve months will fly by. But what about the math for a broken friendship? Does the “total time together, divided by two” equation still hold true? Is there math for that kind of loss? Can you heal by acquiring a new friend, much in the way a new love can often heal you?

My friendships have been my haven — where I can go when nothing feels right in the world. I can say things to friends I cannot say to anyone else. Because the very fabric of friendship feels unbreakable, I’ve never worried if I’m going to mess up and suddenly end up on the outskirts of their affection.

On the contrary, I have expected to lose romantic loves. Read a book, watch a movie — romantic love is not built to last. It makes sense, right? What kind of relationship can flourish under that kind of intense pressure? Romantic relationships tend to confine us. Fit here, do this, be this, make me feel this. Friendship accepts you as you are. Friendship — oh, glorious friendship — with its giant, flexible confines of acceptance.

When I lost a friend I’d had for 20 years, I was devastated. It was unlike the loss from any romantic breakup I have known. Our love wasn’t chemical, or nonsensical — our love was based on true connection and uncomplicated feelings. Losing her was one of the most intense griefs I have ever been through.

I met her when I went to college. She was one of the first relationships I had that was completely severed from my home. For the first time, I was allowed to create a family away from the family of my origin. Gone were the ideas that you had to tolerate those born around you. This was freedom. The freedom to create camaraderie — the freedom to essentially create a new family. This chosen family took on a role my family members had never filled — the chosen ones, I thought, could not leave me. How could they? No one made them choose me. They chose me, headfirst, knowing me. I thought friendship was the safest kind of relationship I had ever found, flat out. I was right. And I was wrong, too.

She looked like Lea Michele and was the funniest person I had ever encountered. We became roommates and spent every day and night together. We played games and ate snacks and attended parties and laughed. She often made me laugh so hard it hurt. She was fashionable and had the prettiest brown eyes on this planet. They sparkled like they were filled with tiny crystals. Our friendship wasn’t perfect, but that’s the thing about friendship — it doesn’t need to be.

Our friendship wasn’t perfect, but that’s the thing about friendship — it doesn’t need to be.

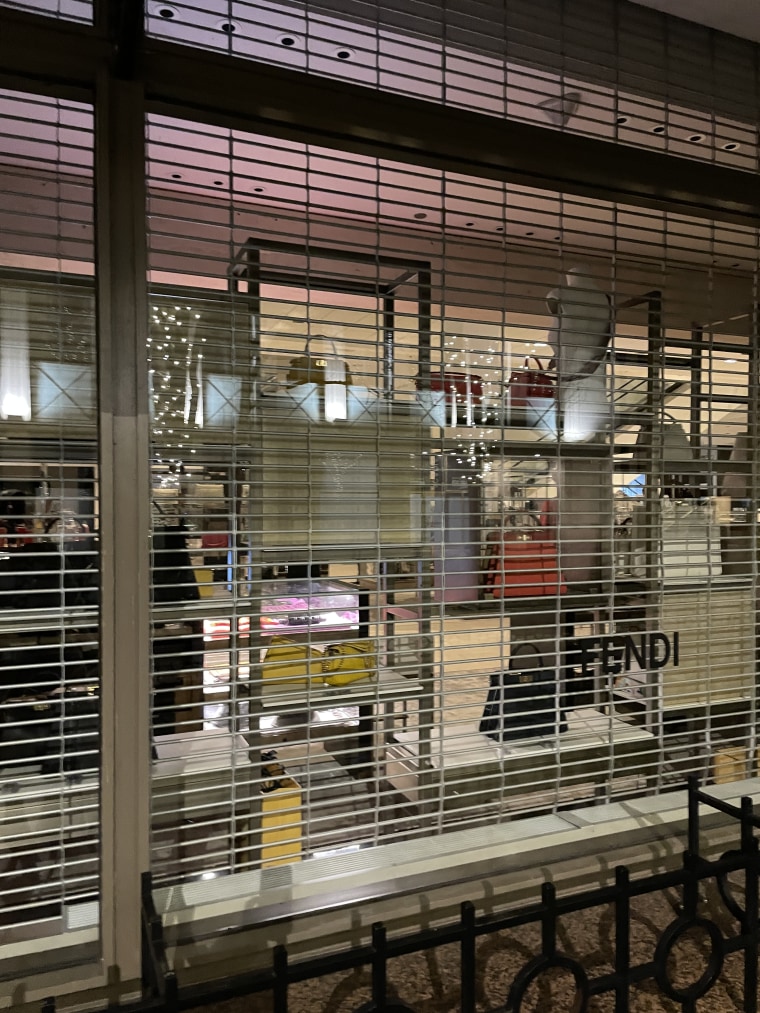

We remained friends after college and ended up in the same place: Chicago. We no longer lived together, but the rhythm of our friendship remained. Weekday evenings, I’d leave the office where I worked and walk 10 minutes to wait for her to finish her shift at a department store downtown. I’d peer into the glass, past the mirrors and shiny products, and wait for her to look over and spot me — then I’d perform an impromptu jig, hoping to make her giggle. On weekends, we’d bike from neighborhood to neighborhood, eating everything the city had to offer.

For the first three to four years after our breakup, I lived the loss of her as if it were a death. Grief caught me at odd times, and at all times. She was fused into so many parts of my life and memories that I could barely get through one day without her popping into my mind. Eventually, I got rid of everything in my house that reminded me of her — everything. Including an amazing sweatshirt that she’d given me one day. I looked good in it and I loved it. But every time I put it on, the only thing I could hear in my head was: People can stop loving you whenever they want to. Which is true. But it’s not a super cozy feeling, and sweatshirts are designed to be cozy. Of course people can stop loving you. But that’s not something we need to be thinking about all the time. So one day, I packed up the sweatshirt and dropped it off at Goodwill.

It was only recently that I came to understand the truth of how and why our friendship ended. It wasn’t that she uninvited me to stay at her home a day before I flew across the country with my husband and newly 1-year-old son. It wasn’t that I ended up forgoing the visit to her entirely. It was that there was a crucial moment in time in which neither of us had the ability to make each other understand what was happening inside ourselves; neither of us knew how to give that vulnerability to the other person without fear of hurting them. I can only ruminate on why I think she asked us not to come to her living space. She said it was about there not being ample space, but I think more was going on. I was too shocked and hurt to ask if there was something deeper happening. And instead of being sincere about my hurt, and about our discomfort with staying elsewhere, I canceled. In the absence of deep and brutal honesty, we were left with the only thing that can be substituted for them — our only choice was to abandon.

It’s been six years now, and I finally feel differently. Until now, it was painful to merely think of her existence. I had such a hard time understanding she could be in this world and not want me in hers. But starting in year five, I began to finally reach something like acceptance. My shock began to subside. I no longer cannot believe we are not friends. I know it now, the way I know about other disappearances. My mother died a few years ago. As it turns out, people often leave — for myriad reasons — no matter how surely we believe in the permanence of their presence.

My longing for her has subsided finally, too. This past weekend, I walked past the door in downtown Chicago where I used to wait for her at the end of our workdays. I took a picture on my phone. I took four, actually. Snow was lightly falling in the night air. I tried to capture how it sparkled in the street lights. I took a couple slightly different angles that I thought might urge her to remember how valuable our friendship was — how valuable I was.

For the first time in six years, I felt grateful for the friendship we had had, instead of resentful that we no longer have it.

But I didn’t send them. Instead, I went back through the photos on my phone, alone in the dark at home, and remembered how much I had loved her. How much fun we once had. For the first time in six years, I felt grateful for the friendship we had had, instead of resentful that we no longer have it. I sat there, composing versions in my head of the most perfect text message I could send to tell her all of this. And then I stopped composing, and I deleted all of the photos but one.