I’m in my 50s and fat; I wear a women’s size 16-18. Still, I’m basically healthy and active. Almost three years ago, my wonderful, warm, longtime primary care physician retired, and I started seeing a different doctor. This new doctor, a few years younger than I, focused in our first meeting on urging me to lose weight. She suggested I go on injected weight-loss drugs, which at the time were just starting to get popular.

As a longtime journalist, I asked for a little time to ponder. After a dive into the literature, I emailed the doctor — let’s call her Dr. Nah — saying I’d prefer not to take the drugs. For me, the side effects seemed a lot to deal with; there weren't any 10-plus-year human studies on continuous use of the drugs; and research indicated that going off the meds would mean regaining most of the weight I lost.

Look, I’d be lying if I said I love my body. I want to; I really do. But we live in a world of biases toward and stigmas about fat people; I experience prejudice all the time. That said, I think I’m smart and funny and (when I want to be) charming, and I have cool hair and a sparkly smile and I’m pretty good at fashion.

I simply didn’t want to become thin by injecting a medication. So I emailed Dr. Nah, saying, well, “Nah.” And furthermore, I told her, I didn’t want to engage in weight-loss talk. “We can discuss eating well and exercising,” I told her, but not with weight loss as the goal. “If that won’t work for you, no hard feelings,” I concluded the email. “I can look for another PCP.”

A few hours later, another email popped up in my inbox, from a doctor I’d never met.

If you like her, and you can remember, you can try to always say “exercise and low-calorie diet can reduce the stress on your liver,” since she says you are allowed to talk about diet and exercise. If she is not worth trying to dance around your language, she is giving you a clear option to say “seeeeeeeyaaaaaa.”

Wait, what? I sat at my desk, dumbfounded.

But I quickly figured out what had happened. Dr. Nah had forwarded my email to a fellow doctor, a friend, asking for advice on how to handle me. The friend — let’s call her Dr. What — thought she was writing back to Dr. Nah but instead wrote to me.

Oops.

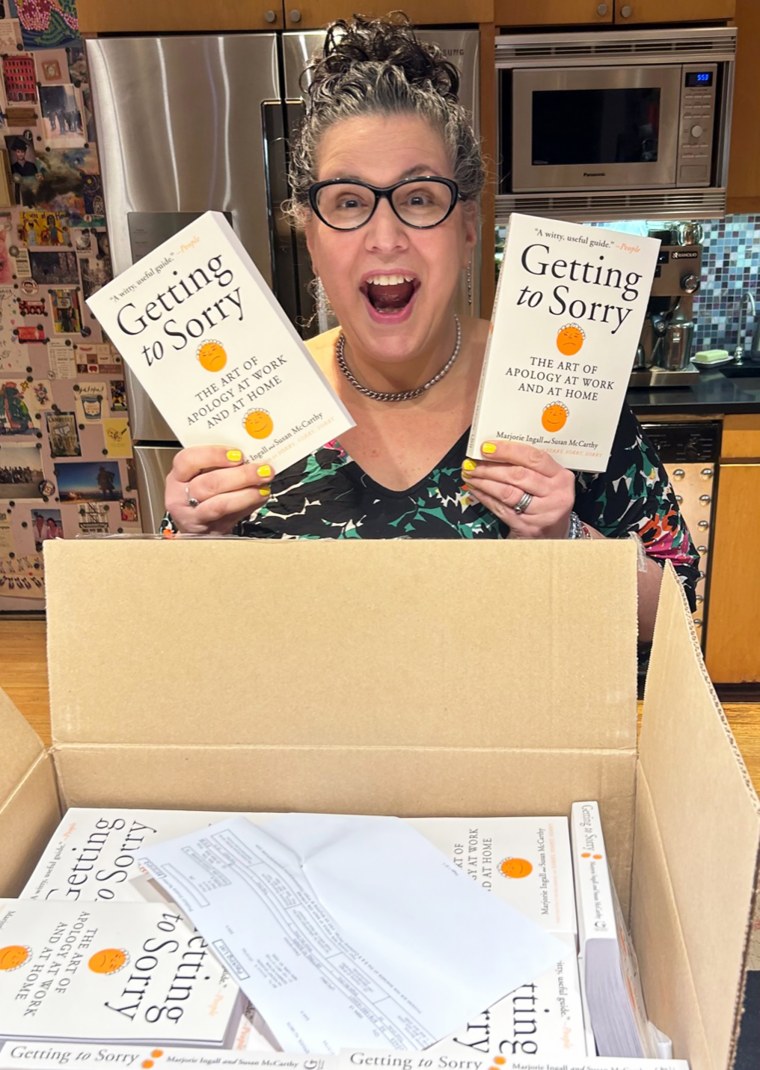

I considered a bunch of possible responses, many involving words I can’t say in this essay. Then I thought about my many years of research and writing about how to elicit a good apology from someone. As a co-author of a new book about apologies, I know that apologizing well is hard, and people usually don’t respond well to shaming or threats. So instead, I went for cheerful but pointed, with a faint gloss of snark. I added an indication, via a link to a scientific study, that I was speaking from an informed place. And I called her on her dismissive, “not worth it” language, but not in a nuclear way that ended all possibility of conversation. My reply:

I’m guessing this wasn’t intended for me. :) (But sure, good advice!)

--m

PS. Here is a journal article you might find of interest.

PPS. Much like L’Oreal, I believe I am worth it. Or at least that I have inherent worth and am deserving of respect as a person. Thanks!

Then I went out for a walk. When I got home, I’d missed three phone calls. There was another email from Dr. What.

I am very sorry that I sent that to you. I am very embarrassed when I read it to imagine how cold it sounds. I am sure any apology reads as very hollow. I did just call but your phone went directly to voicemail, so I could try to apologize live rather than under the cover of e-messaging.

Medical training has many failings. I have demonstrated one very large failure with that message, which you did nothing to deserve and I deeply wish I could undo it.

I was only able to read the abstract of the article you linked.

This is a link which may speak to the same truth.

I apologize again for sending a message that was alienating. You did nothing to deserve that and I am sorry for inflicting it on you in my carelessness.

Whoa. That was ... a really good apology. My co-author and I have researched what makes an apology effective, and this hit almost all the high points.

For example, we’ve found that a good apology uses the phrase “I’m sorry,” or “I apologize,” rather than “I regret.” When I say “I regret” something, that’s about my feelings, my guilt, my shame. A good apology puts the other person’s feelings front and center. A good apology demonstrates understanding of the harm done, takes responsibility for causing pain, and lets the other person know that their feelings are legitimate. And Dr. What nailed it. That’s why, years later, I’ve still saved the entire email exchange.

My heart still hurt from the initial wound, but Dr. What’s apology made me feel a lot better. The fact that doctors aren’t exactly known for apologizing well made her words feel even more powerful. I wrote back saying, “Thank you for the apology.”

My co-author and I have also found in our research that people tend to respond well to a thank you because it acknowledges that they’ve done something difficult. And apologizing well really is difficult! That’s because most of us see ourselves as basically good people; when we’re presented with evidence that we did a bad thing, we tend to resolve this contradictory information in our own favor. We convince ourselves that what we did wasn’t that bad, that the other person deserved it, that they owe us apologies, too. We use phrases like “sorry if,” “sorry but,” and “sorry you took it that way.” We slip into the passive voice (“Things were said ...”). We use phrases like “out of context,” “not who I am,” and “misinterpreted.” I wanted to give Dr. What credit for not falling into that trap.

Then, Dr. Nah called me. She was nearly in tears. I told her it wasn’t her fault, which was true, and that I hoped if I continued as her patient, she could see me as a person, not a problem. She swore up and down that she could, and she would.

And she has. Two and a half years later, she’s still my doctor. I think the incident improved our relationship. She’s done her best not to discuss weight loss, though it’s not natural for her. (I haven’t found a truly weight-neutral doctor here in New York City. Let me know if you know of one.) She makes time to chat — a rarity in our world today. She’s asked my advice on parenting. The power dynamic in our relationship feels different and healthier. When one of my kids was diagnosed with a chronic illness, she helped me find resources for her.

Behold, the power of good apologies — giving them and accepting them. Saying you’re sorry and then taking concrete steps to prevent a recurrence of the error can create something good out of something bad.

Every new year, a lot of us vow to lose weight. And no wonder, it’s challenging to live life as a bigger human and even harder when talk of weight-loss drugs and their effects seems to be everywhere. I don’t judge anyone for making choices they feel are right for them. But I do wish that when we consider our New Year’s resolutions for 2024, more of us would choose a less common aspiration: To apologize better. Doing so might not make us thinner, but it could create a kinder world.