Sarah Gray's son lived less than a week, but uncovering his lasting legacy has helped his mom turn grief into pride.

“Even though Thomas only lived a few days, he’s made an impact on the world in his own little way,” Gray, who lives in Washington, told TODAY Parents.

Gray became pregnant in late 2009, but the joy of learning she was carrying identical twin boys soon turned to anguish when she found out at her 12-week checkup that one of the babies had anencephaly, a birth defect that results in a child being born without parts of the brain and skull.

Doctors told Gray and her husband Ross that the boy would die when he was just a few minutes, hours or days old. Amid that awful news, Gray began thinking about donating his organs, though she doubted a baby with a birth defect would be a suitable candidate. It turned out the boy’s organs were very valuable — not for transplant, but for research, the local organization that arranges donations told her.

Gray carried the babies almost to full term and gave birth via a cesarean section on March 23, 2010.

Thomas, the baby with anencephaly, was born first, weighing 4 pounds and 1 ounce.

“The nurse said to me, ‘His heart rate is dropping, we may lose him soon. Do you want to see him?’ I said yes,” Gray, 41, recalled.

“I stroked his cheek with my finger and I said ‘I love you’ and I shed a tear. And as I was talking to him, they checked his heart rate after that. I thought he died right there. They took him away and they said his heart rate was back up, he’s doing better.”

Thomas’ twin brother Callum was born healthy, weighing 5 pounds and 10 ounces. The Grays took both boys home, where Thomas died when he was six days old. His life was filled with love: His parents got to hold him and cuddle him and he slept in their arms, Gray said.

The Washington Regional Transplant Community transported his body to the Children’s National Medical Center, where doctors recovered his eyes and his liver. The family also allowed the boy’s umbilical cord blood to be donated at the time of his delivery.

Gray knew which institutions received her son’s organs, but there were no other updates.

“I sort of let it go. Like, OK, that’s all we know, so we’ll just have to be happy with that. We donated and it went to a good cause,” she said.

Then, in the summer of 2012, she traveled to Boston on a business trip. She knew the corneas from Thomas’ eyes had gone to the Harvard-affiliated Schepens Eye Research Institute, which happened to be just a few miles away from her hotel.

“I called them and I said, ‘I donated my son’s eyes to your lab and I’m in town for a few days, could I come by for a tour for 10 minutes?’” Gray said.

The institute had never had a visitor like her, but officials arranged a visit and told her that donated infant eyes, like Thomas’, were extremely valuable for research. They showed her a study that featured photos of cells from her son’s corneas, which has since been cited by 14 more studies.

“I had such a good experience and something in me shifted after I visited that lab. I felt my feeling of grief change into pride,” Gray recalled.

Eager to know more, the family soon traveled to Durham, North Carolina — home to Duke University, where Thomas’ cord blood was sent; and Cytonet, a biotechnology company that received his liver.

Researchers in both places told the Grays about the critical studies they were able to complete thanks to Thomas’ organ donation. Gray was so proud that she bought a Duke T-shirt for Callum.

But there was one more piece of the puzzle left. Last year, Gray was surprised to discover Thomas’ retinas ended up at the University of Pennsylvania, so she contacted the researcher who received them. Arupa Ganguly wrote her back, telling her how grateful she was for the donation. Soon, they too were arranging a visit.

“I felt bad as a mother that I’m talking to another mother who has lost her son,” said Ganguly, a professor of genetics, who studies retinoblastoma, a childhood eye cancer. “I connected with her… I thought this is someone who wants closure.”

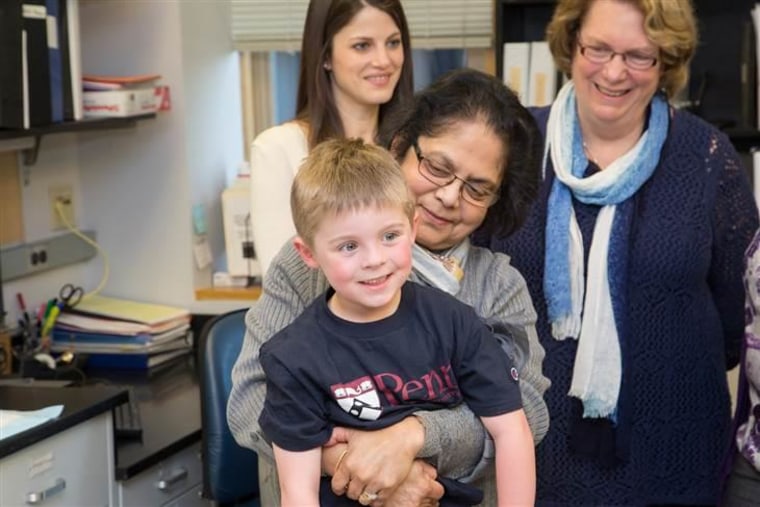

On March 23, Thomas’ and Callum’s fifth birthday, the two women met, with Gray and her husband finding out more about Ganguly’s lab and Callum getting a special celebration from the research team. Ganguly told Gray that Thomas’ retinas were very precious because the lab needed healthy samples from newborns, but has been able to collect just a few.

Gray considers it just another part of Thomas’ legacy. She has become so passionate about the cause that she now works for the American Association of Tissue Banks.

“These researchers are wonderful people. It’s been really gratifying to meet them. It’s almost like our son is introducing us to these people,” she said.

“He’s teaching us still and he’s teaching them.”

She urges parents who find themselves in a similar situation to contact the Association of Organ Procurement Organizations.