Our roundup of winter fiction includes some true powerhouses. The legendary Tom Wolfe goes back to college — as a woman — in "I am Charlotte Simmons." It's large enough that even when you're not reading it, you can use it as a doorstop to prop the dorm door open.

Another legend, John Updike, has also returned, with "Villages." Our critic found the writing entertaining as always, but wishes Updike would branch out a bit from his well-trod favorite territory of white middle-class men.

And just when you thought it was safe to go back into the tollbooth, college professor Mark Winegardner resurrects the Family Corleone in the eagerly awaited "The Godfather Returns." For fans, is it an offer they can't refuse?

A good ski-lodge readIf it were summer, I would say that Thomas Kelly’s “Empire Rising” (Farrar, Strauss and Giroux, $25) would make a perfect beach read. In winter, it’s the perfect book to take with you to the ski lodge or on that escape-from-the-cold vacation. Light with uncomplicated characters and a colorful setting, the book spins a good yarn of Irish immigrants in depression-era New York City when the Empire State Building was being constructed.

The book focuses on three main characters. Michael Briody “throws iron up” on the Empire State building while saving money to send guns home to those in the Irish Republican Army. Jimmy Farrell is the savvy political figure who forgets his Irish roots in attempt to advance his career. Grace Masterson is an artist who lives on a boat and who gets in deep with a money laundering scheme while falling in love with Briody.

The characters are pretty simple. There are good guys and bad guys and not a whole lot of gray areas. The hard-drinking Irishmen and mobbed-up Italians will be easily recognizable to most. Still, they’re an enjoyable lot. Particularly the marginal characters, like Tough Tommy Touhey, who runs the Irish Bronx with gusto, but doesn’t share Farrell’s ambitions.

The strength of the book is in the setting and the way that Kelly seems to really know the history of the Empire State Building and how the iron workers would have actually created its skeleton — some losing their lives in the process. Kelly is a former construction worker, so it’s no surprise that he knows his stuff. The politics of Tammany Hall with its kickbacks and brides and influence on national politics also creates a fascinating backdrop. —Paige Newman

A welcome return

It’s been 23 years since Marilynne Robinson’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel “Housekeeping” was published. Since then, she’s written two works of nonfiction, but now, finally, her second novel, “Gilead” (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, $23) is in bookstores.

“Gilead” is the story of three generations of preachers. At 77 and with a heart problem, Reverend John Ames knows he’s not going to be around much longer and the book is composed as a letter from father to son. Ames wants to explain where he came from and who he is to the young son who’s not old enough to really know him yet. Ames’ grandfather was a preacher who carried a pistol and fought with the abolitionists during the Civil War. Ames’ father, in turn, was a pacifist who never understood his own father’s violent ways. Ames documents the tension between them and how knowing them both informed his own way of dealing with the world.

The book also tells the story of the son of Ames’ best friend, Jack Broughton, and Ames’ fears for his much younger wife once he finally passes. This is the strongest section of the book – it was hard not to wish Robinson had simply written a book about conflicted outsider Broughton instead of Ames.

It’s hard not to admire Robinson’s prose here; each sentence seems to have been created with the precision of a watchmaker. Yet, there’s something almost cold about the book. It’s a bit like watching a great acting performance, yet never really getting beyond admiring the technique. At times, the passages can almost read like sermons — appropriate for a minister, but a bit numbing for the reader. Still, you can’t discount a talent like Robinson, and aspiring writers especially should take a lesson from her clean and intentioned prose. Let’s hope we don’t have to wait 23 years for her next book. —P.N.

An offer he couldn’t refuse

For many people, the movie versions of "The Godfather" have replaced Mario Puzo's book version, and that's a shame. Puzo's novel is every bit as sweeping as the films, and carries a cruel edge that Hollywood smoothed over. (Not to mention the infamous "Sonny and the bridesmaid" scene.)

Puzo died in 1999, but in 2002, author and college professor Mark Winegardner was selected by Random House to resurrect the family Corleone in "The Godfather Returns" (Random, $27). An enviable task in some ways, not in others. Like Alexandra Ripley with her "Gone with the Wind" sequel, "Scarlett," Winegardner just can't please everybody.

He holds up his end of the deal fairly well. We meet a few new characters — Sonny's daughter Francesca held my interest more than Corleone enforcer Nick Geraci — and are reunited with some old ones. Winegardner proposes an interesting spin on Corleone brother Fredo's personal life, but his twist of history regarding Kay Corleone’s abortion feels like a cop-out. He also hews too closely to actual events of the 1960s in some areas, to the point where I wondered why he didn't just rename singer Johnny Fontane to Frank Sinatra and get it over with.

It's hard not to read a Mob book today, even one about the storied Corleones, and not think of HBO's "Sopranos." Yet we don't get to know this Michael as well as we know TV's Tony, and that makes it tough to slog through some of the book's 430 pages. Winegardner is no Puzo, but "Godfather" fans will want to pick this one up for old-time's sake. —Gael Fashingbauer Cooper

Sweet ‘Charlotte’Vanguard journalist and legendary novelist Tom Wolfe drops his trademark white suit for some khaki shorts and a college sweatshirt as the author of “Bonfire of the Vanities” and “A Man in Full” returns to campus to bring us “I Am Charlotte Simmons” (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, $29). And folks, a lot has changed in the hallowed halls.

Wolfe centers his trademark multi-character novel around an academic ingénue named Charlotte Simmons, fresh from the mountains of North Carolina – ready for academic stimulation but ill prepared for what really awaits her at Dupont University, an amalgam of Stanford, Michigan, North Carolina and Alabama. And what is that? Drunken frat boys, athletes with all-star jump shots who lay bricks in the classroom, snobbery – oh, yeah, and the sex. Lots and lots of sex.

Many reviews of this book have been less than kind, and fault Wolfe for being out of touch and too old to cover the subject at hand. Perhaps, but if you think his recounting of the exploits on campus are exaggerated, already passé or overly simplified, when was the last time you spoke with a college student? At 676 pages, it can be intimidating, and yes, Wolfe does tend to overwrite at times (as an editor, I fought the urge in some parts to pull out the red pen). But that was also where the gems where found, most especially his lengthy dissertation on the various uses of the F-word. For those expecting higher prose, pick another book. He is offering a super-sized tale about the fast-food, fast-living generation, beer bong included.

He develops out his characters in detail, from basketball-star Jojo Johanssen to geeky Adam Gellin, to big-man-on-campus Hoyt Thorpe, to our heroine, Charlotte. Each reflected somebody we all knew on our college campus, love them or hate them. I found his depiction of Johanssen and the cult of alpha-male superiority surrounding major college athletes (or mediocre ones for that matter) dead-on.

As was his Charlotte. For all those who were the Charlottes — bright, naïve, lonely, dead sure of your convictions, inexperienced and scared to death — the reflection Wolfe casts is crystal clear. Only through experience, great and horrible, does Charlotte start to see the real world for the first time. — Denise Hazlick

A taste of Lethem

It’s not surprising that Jonathan Lethem’s latest collection of stories, “Men and Cartoons” (Doubleday, $20) disappoints. After all, it comes on the heels of two rich and satisfying novels: “Motherless Brooklyn” and “Fortress of Solitude.”

The best of these stories — “Super Goat Man,” “The Vision” and “The Spray” – demonstrate what makes Lethem such an enjoyable writer. He creates worlds where ordinary people can be mistaken for superheroes and where the fantastic happens without the characters ever losing what makes them human. If his writing weren’t so down to earth, he might even be mistaken for a magical realist.

“Super Goat Man” tells the story of a hippie college professor who may or may not have super powers. In “The Vision,” grade-school nemeses meet up as adults at a cocktail party with awkward results. “The Spray” gives a futuristic crime-solving technique that has unique personal results for one couple.

There are some clunkers here: the futuristic “Access Fantasy” in which people are forced to walk around spouting off advertisements feels fragmentary — like an idea Lethem just wanted to try out. While “The Distopianist: Thinking of His Rival…” seems a bit too clever for its own good. Still, Lethem is one of the best writers around and if you don’t have time to dive into one of his terrific novels, this short story collection could be a great place to start. —P.N.

‘Seeds’ is a mixed bag

The latest book from Nobel Prize-winning author V.S. Naipaul is a sequel of sorts to his critically acclaimed novel, “Half a Life.” “Magic Seeds,” (Knopf, $25) continues the saga of Willie Chandran, who, at the opening of the novel, we find out has left his wife in Africa and is now staying with his sister in Berlin.

It’s hard not to have mixed feelings about the novel. On the one hand, everyone Willie encounters is fascinating. His character winds up joining a group of guerrillas in India and each time he’s paired with a new “partner,” we get that tale of how that person came to be a guerrilla – all of the tales are different and give unique pictures of life in India. His London friend Roger is another great character with an interesting story of how he came to have and lose his mistress. When Willie finds himself in jail at one point in the novel, the descriptions of the different castes of prisoners really show a lot about Indian society as a whole. Again, I found myself compelled by the story.

On the other hand, there’s Willie himself. His character is so passive throughout the novel – and who would have thought there could be such a thing as a passive guerilla – that it’s hard to feel too invested in his story. He even has sex passively. It’s almost as if he exists only to string the other more interesting stories together. It was never clear why he became a guerilla – it almost comes off like a whim, or an echo of his father’s turn away from his privileged life that appears in “Half a Life,” as if Willie is doomed to unknowingly repeat his father’s mistakes.

The novel is certainly worth reading, but primarily for the stories of others and not for the story of the main character. —P.N.

New worlds in ‘Noodle Maker’

A great book can give you entry into a different world. Ma Jian’s latest, “The Noodle Maker,” (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, $21) does exactly that, giving the reader a taste of what post-Tiananmen Square China is like. From the one-child laws to the restrictions on what books and music can be listened to the dog extermination brigade, the realities of 1990s China seem almost unreal. Yet, this is not a depressing book. In fact, it’s humorous. LikeNikolay Gogol, Ma Jian illustrates his society’s problems by satirizing them.

The book really starts as a discussion between two people: one, a poor professional writer (being paid to glorify his country in words) and the other, a blood-donor, who has created a black market of illegal donors. When the blood-donor challenges the writer to write what he would if there were no restrictions, it unleashes the rest of the tales that fill the book. In one, a man finds a way to make money by opening a crematorium. In another, a woman decides to take her own life in a performance art piece involving a tiger. In yet another, the owner of a recently killed dog remembers back on their long discussions. Structurally, the book takes as many risks as it does thematically. Ma Jian links the stories together in unexpected ways and gives you a clearer picture of the writer and the blood donor through the telling of those stories.

Ma Jian has been described by Nobel laureate Gao Xingjian as “one of the most important and courageous voices in Chinese literature.” The chance to hear a voice like his is a reason to love books. —P.N.

‘Runaway’ works on many levels

Alice Munro may just be the best short-story author writing today. She’s a writer who makes you appreciate the form as something more than what novelists do when they’re not ready to start a new novel. Like Chekhov, Munro has expanded the idea of what a short story can do – that you can have the layers of irony and pathos in 40 pages that some novelists are unable to create with 400. In her latest collection, “Runaway” (Knopf, $25) her talents are once again on full display.

The centerpiece of the collection is three linked stories about a woman named Juliet. In the first, we meet her as a young woman who finds love on a train one night and decides to chase it. In the second, we see her as a young mother who goes to reconcile with her own parents and her ideas about faith. In the third, she’s an older woman estranged from her daughter who wonders what’s become of her life. What’s amazing about Munro’s storytelling is her economy of language and the fact that there’s almost no exposition. Juliet becomes a different person and her life changes in ways that seem both natural and totally unexpected.

Perhaps the best story in the collection is the final one, “Powers,” about one woman who has the ability to see future and another who can’t even seem to see what’s occurring in the present. Her use of description, as in one scene with “seer” Tessa, now in a mental institution, working in the bakery with a mute woman who makes dough mice, is incredibly vivid. The reader sees what Munro writes as if she’s describing what’s taking place directly in front of her instead of something drawn from imagination.

If you’ve never read Munro, this book offers a perfect place to get started. If you’re a fan like I am, once again you’ll find yourself wondering just how she does it so well. —P.N.

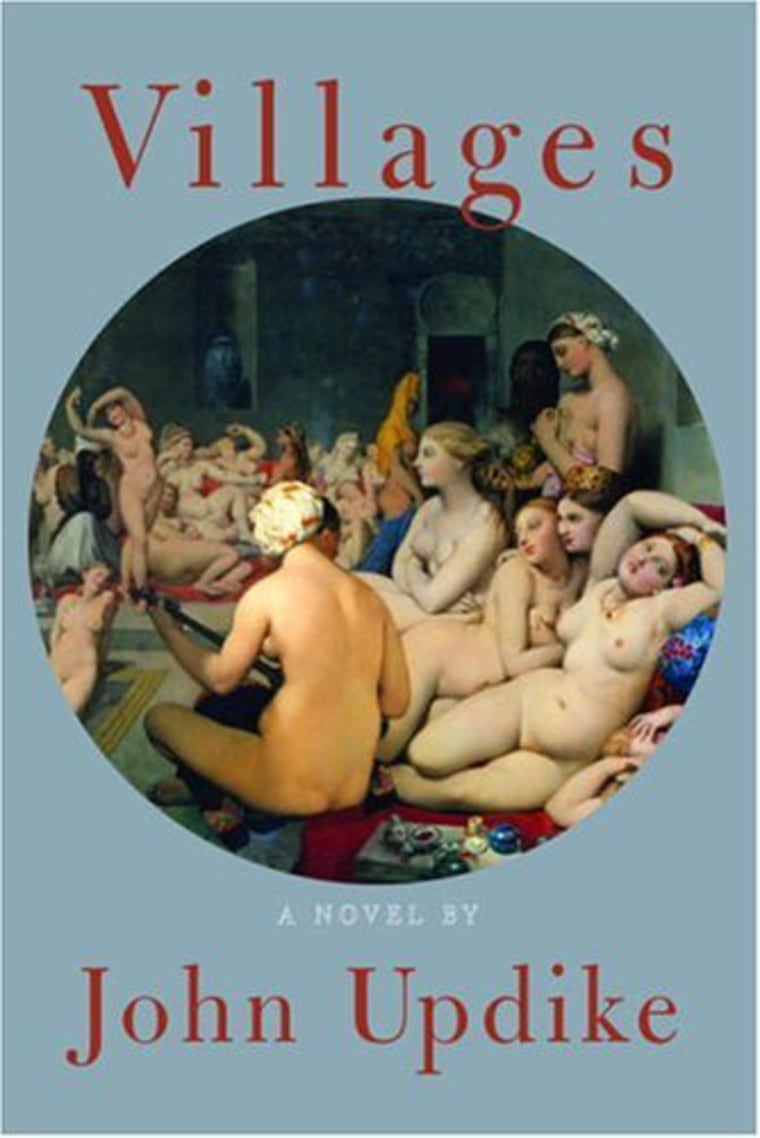

Randy ‘Villages’John Updike writes about a very specific world that’s comprised almost solely of white middle-class men and the women who give them pleasure and pain. In his latest book, “Villages” (Knopf, $25) he goes back to similar territory producing a book that’s entertaining but not very surprising.

When we meet Owen Mackenzie, it’s the 1990s and he’s in bed with his second wife Julia. The story to come will be how he got here and who he hurt and loved along the way. Updike takes us from Mackenzie’s upbringing in the small Pennsylvania town of Willows to his years at M.I.T. to his life with Phyllis in Middle Falls, Connecticut to present day with Julia in Haskells Crossing. The four “villages” almost become characters in the novel. Middle Falls is claustrophobic yet homey (not unlike Wisteria Lane in “Desperate Housewives”), whereas Haskells Crossing is a place to hide, a new start where even a couple in their 40s can still be considered “young.”

The most troublesome, yet entertaining, part of this book is the way that every woman Owen encounters wants to have sex with him. It’s like some kind of male fantasy gone awry. Owen is described as a somewhat mild-mannered computer programmer and it was never clear to this reader what the many, many women he beds found so attractive about him. His sexual conquests are the center of the novel, yet they never seem like more than fantasies. Computer programmers never had it so good!

The writing here is entertaining and I read this at a steady clip, but Updike’s world of isolated New Englanders just isn’t that compelling for someone who dwells today’s more complicated world. Maybe it’s time for him to start exploring some new subjects — or better yet, go back to writing some short stories where he can experiment a bit more. —P.N.

Paige Newman is MSNBC.com's Movies Editor. Gael Fashingbauer Cooper is MSNBC.com's Books Editor. Denise Hazlick is MSNBC.com's lead Entertainment Editor.