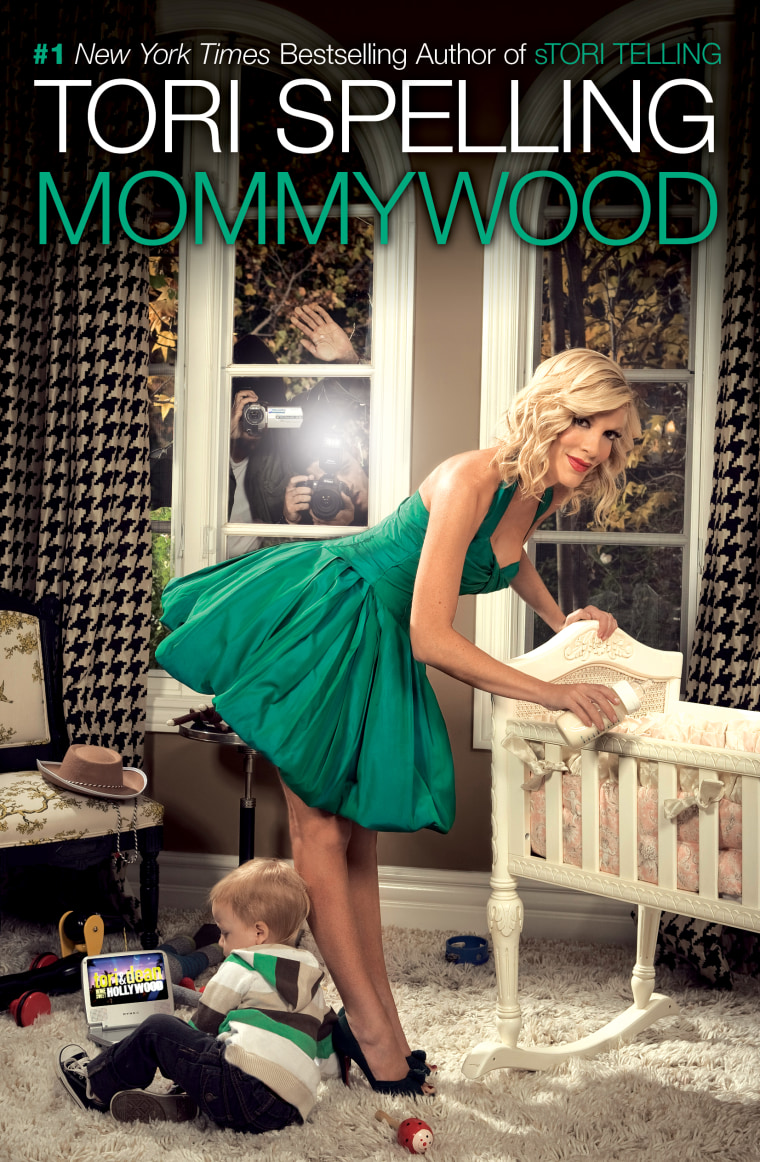

Tori Spelling might have grown up with everything a girl could wish for, but like most parents, she wants her children to have the one thing she didn't have — a normal family. In her new book, “Mommywood,” the star tells stories of life as a mom in the limelight. In this excerpt, she writes about bringing Hollywood's superficial standards into the doctor's office.

Near the end of my first pregnancy my husband, Dean, and I went to an appointment for an ultrasound. It was always exciting to see the fetus by ultrasound, but this time it would be a special, 3-D ultrasound — an amazing new(ish) technology that allows patients to see a clearer picture and doctors to bill insurance companies more. Instead of the usual staticky, hard-to-discern image, we’d be able to see exactly what our very own baby looked like floating in my belly. It felt like this was the moment when we’d be meeting our little miracle for the first time.

The doctor squeezed the self-warming goo on my belly and started moving the wand around. We already knew that the baby was a boy. Now the doctor was saying calming, nonspecific things like “Looks good ... all good. There’s his little foot ...” Actually, who am I kidding? I have no idea what the doctor was saying. For all I know he said, “You’re having six babies and you’ll be delivering them through your ear,” because something had me distracted. I was focused on the screen, staring hard at my baby’s delicate face. There he was, all perfect. Head, eyes, ears, but, well ... I didn’t want to admit it, even to myself, but something was bothering me. His nose. I kept coming back to it. I was worried, well, it’s just that ... it looked a little — was I even allowed to think this? — it looked a little, um, large.

As soon as the thought entered my mind, I tried to shut it down. I kept trying to look at the rest of the baby. Skinny little legs ... nose. Teeny tiny hands ... nose. Heart — a little heart that you could already see beating! One of the most incredible sights anyone could ever witness — nose!

Maybe this was one of the many facts about fetuses I’d skimmed over in all those having-a-baby books I’d bought and really, really intended to read by now: you know, “Babies can look blue at birth.” “Their eyes are puffy.” “The umbilical cord resolves itself.” I racked my brain: was there anything I’d read about ultrasounds making noses look exaggerated? Or noses being out of proportion at birth? Yeah, yeah, wasn’t there something about that?

At last I couldn’t help myself any longer. I pointed at the screen and asked the doctor, “Is that true to life?” He replied with something overly scientific about the way the sound waves are reconstructed and the surface and the internal blah blah blah. Not very helpful. Inside my head I was screaming, Oh my God, does he have a huge nose? Just tell me! but I was having trouble asking it directly. I knew it was wrong to care, but I did. So I tried to put it as delicately as I could: “Does his nose look ... normal?” The doctor nodded. “Of course, of course,” he muttered. Hmm. That still wasn’t really satisfying. I timidly ventured, “You don’t think it’s a little big on his face?” Glancing up at the screen he said, “It’s possible he’s pushed up against the placenta. That could distort or exaggerate the features.” Okay, now we were getting somewhere. I said, “So it’s a normal-sized nose?” The doctor reassured me that my baby would come into the world with a nose that was ready and able to breathe. You know how doctors can be. They assume “normal” means “healthy” — so respectable, so nonsuperficial, so not what I was looking for. “Healthy” was good news, very good news, the best news. But not exactly what I was worrying about right then.

On the way to the car Dean was quiet. Once we had gotten in and were driving, he finally said, “I can’t believe what I just witnessed.” Uh-oh. Dean sounded angry. He went on, “We were looking at a beautiful, healthy boy — our baby! — and you’re worrying about the size of his nose?” Well, of course the baby’s health was what mattered the most! I worried about that every day. But this was the super special 3-D ultrasound, the one where we saw our baby moving in three-dimensional space. Once all vital signs looked good, wasn’t I allowed to want a cute baby? I told Dean, “I couldn’t help it. I said what I was thinking. It came into my head, and I wanted to know. Should I have just sat there wondering in silence?” Dean sputtered, “Are you really that shallow?”

Suddenly it hit me. I was picking apart my unborn baby. I couldn’t help but flash back to the day my mother told me I’d be pretty “as soon as you have a nose job.” I always claimed, only half joking, that that moment had scarred me for life. And now here I was worrying about the facial features of my own child, before he even had a chance to breathe air. At least my mother had the decency to wait until I was twelve to start in on me. Was I a hypocrite? Was I destined to replicate the mistakes my mother had made?

Mothers are supposed to think that their children are gorgeous no matter what. What if I didn’t? What if I’d inherited some mutated gene from my mother that caused us to feel nothing but disappointment in our offspring? Oh my God, did I have the Joan Crawford gene? It made sense: whenever I saw moms showing off little-old-men babies — you know the kind: wrinkled, puffy, and world-weary — much as I love babies, part of me always thought, Can you not see that you’ve got a mini Ed Asner on your hands?

As soon as we got home I called my friend Jenny. Jenny was pregnant with her second baby and I knew she’d be honest with me. I told Jenny what had happened at the doctor’s office.

She said, “Are you kidding? I do the same thing. That’s what girls do.” Jenny said that once we feel reasonably sure that the fetus is healthy, we assess the features of all family members, immediate and distant, and assemble them into a vision of the ideal genetic descendant. Then we watch closely to see how the baby’s features line up against that vision. “It’s totally normal.” I was a little relieved. I might be shallow, but at least I had company. Later, when Shane, Jenny’s second child, was born, she’d be the one to say, “Come on over, but he’s no looker.” (Let the record show that Shane is now a gorgeous child and of course Jenny thinks so too.)

Talking to Jenny made me feel better. But then I started wondering. Is that what all mothers do? Or is it what we do — Jenny, me, and all the equally shallow friends around us? Are we normal moms, or are we living in Mommywood?

As anyone who read my first book or has glanced at the tabloids in the last couple decades knows, I didn’t have a normal childhood. My dad, Aaron Spelling, was an extremely wealthy TV mogul. I starred in 90210 — a show that my father produced — for ten years starting when I was sixteen. My mother and I have a difficult (at times publicly so) relationship — when we have a relationship at all. My whole childhood I wished I had a normal family. I’ve spent much of my adult life working to prove that I’m a real person, a normal person, not the punch line of a joke.

Now I have two children of my own and I want them to have a normal childhood. I want them to have a happy life. I want to have a close, loving, joyful relationship with them for the rest of my life (though I realize that the teenage years are a bitch). My mother and I had and have our troubles, but I was raised by a nanny I called Nanny, and I learned plenty about being a good mother from her. Now is the time for me to take what I learned and to be the mother I always wished I had. But knowing you want to do things differently doesn’t mean you know how to escape the way you were raised. This wasn’t just about me worrying about the size of my unborn child’s nose. Now I was struggling with the much greater fear that when push came to baby, I was going to be just like my mother.

I grew up in the public eye. I don’t think of that as a bad thing, but I think it’s pretty obvious that being regularly watched, photographed, written about, and sometimes chased like an escaped prisoner by the paparazzi must have had an effect on me. It’s made me care a little too much about how I and, by extension, my family, look in pictures, be they candids, glossy magazine shots, or — ahem — ultrasound images. Obviously that’s something I have to work on. But what else is there? What other special effects has my unusual upbringing had on me?

How has Hollywood shaped me? How will it shape my children? Can a celebrity be a good mother? Can children grow up in the spotlight without being scarred for life? Will my children play kickball in the street with the neighborhood kids, or will they grow up thinking that the reality show cameramen who follow us around are their best friends? Can I give my children privacy from the media but still let them have friends and neighbors like normal kids? Above all, will my children and I develop the relationship that I had always dreamed of having with my own mother? I may care about a nose for five minutes in a doctor’s office, but these are the real issues that I worry about every day. I want my children to have a happy, normal childhood, but “normal” can be pretty elusive around here.

The fact that my life isn’t normal doesn’t make it any less real. My struggle to balance work and home life may show up on TV sets across the nation, but lots of moms who aren’t on TV have the same challenges. My attempts to get along with my neighbors may be complicated by their preconceived notions of who I am, but I’m still a mother, hoping her children can be friends with the kids next door. I grew up in great wealth, but I work as hard as the next person to make a home, to pay for school, and to give my children a world of choices and opportunities. I strive every day to be a good mom, like moms everywhere.

Hollywood is a glittering, glamorous, superficial land of dreamers, wannabes, and stars. Mommywood takes place on the same set — the palm trees and eternal sunshine of Los Angeles.

But casting is difficult and requires nine months of faithful commitment to rocky road ice cream, plus labor and delivery. The lead roles are played by stars who are finicky, in need of nonstop coddling, and around two feet tall. My own Mommywood life is full of drama (an awkward encounter with a former costar at a children’s birthday party), tragedy (the death of a diva pug), horror (when poo meets pool), and farce (being the only one in costume at a Halloween party), but at the center of it is the greatest love story I’ve ever experienced, greater than any love story on the small or silver screen, the same amazing love story that all mothers go through with their children.

This is the story of my definitely amateur, sometimes serious, often bumbling, never-to-be-finished attempt to make it in ... Mommywood.

Excerpted from “Mommywood,” by Tori Spelling. Copyright (c) 2009, reprinted with permission from Simon and Schuster.