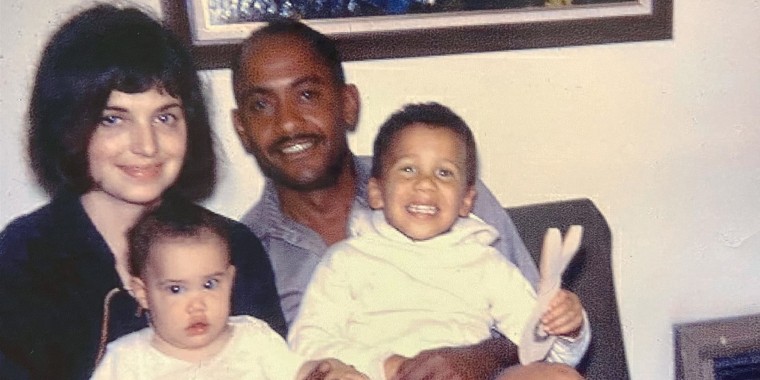

Susan Rogers, 84, forgets the year that she and and her husband, Bill, got married, but she remembers his charisma and the way people naturally gravitated toward him.

She remembers him sitting downstairs with his newspaper and coffee in the mornings, listening to Marvin Gaye’s “Let’s Get It On” over and over.

She also remembers the day her father drove to Bill’s apartment and offered him a wad of cash to “leave her alone.”

Those days feel like a different time, Rogers said. She’s white and Bill was Black, and in the late 50s when they started dating, they were an anomaly. In fact, interracial marriage was not fully legal in the United States until the landmark 1967 Supreme Court decision, Loving v. Virginia.

When Britain's Prince Harry and his wife, Meghan, spoke to the media mogul Oprah Winfrey earlier this month about the racism the former actress who is biracial experienced at Buckingham Palace and through British tabloid media, Twitter users chimed in with support, judgment and shock. It also reminded Rogers' daughter, Lesli Mitchell, 53, of her parents and all they faced until her father’s death in 1997.

“I think my mother felt the pain of racism in her relationship and through her children, similar to Meghan Markle,” Mitchell said.

Meghan detailed the harassment from the media, which often praised her sister-in-law Kate, the Duchess of Cambridge, while putting her down. She also revealed that there were concerns expressed in the royal family about how dark her son’s skin would be before he was born.

While viewers and the media debated who could have made the comment, many interracial couples watching the interview across America felt like they were on familiar ground. Meghan’s experiences seemed like an everyday problem blown up on a royal, colonial scale, they said.

Susan and Bill Rogers settled in Los Angeles — which seemed less hostile toward their relationship compared to Susan’s mostly-white hometown of Eugene, Oregon — and they had two children together. But Bill never got along with her father. Mitchell said she felt a coldness from her grandfather throughout her childhood.

“My older brother is the one that kind of figured out the puzzle of what the problem was,” Mitchell said. “He was like ‘I think grandpa’s racist.’”

She said she felt the need to prove her worth to her grandfather as a child, including making a concerted effort to sound as intelligent as possible in letters she wrote him.

When he died and the family went to Oregon for his funeral, she realized she was meeting almost everyone for the first time.

“There were several people that came up and said, ‘We didn't even know you existed,’” her mother recalled.

Rogers' father hadn’t told any relatives about her husband or kids. She recalls people lining up to greet them. A relative said, “I asked your dad where you were and if you were married or if you had kids, and he said he didn't know where you were.”

“Yeah, that was really weird,” she said, since she had been in regular contact with her father.

While Meghan’s experience may have been different — front and center, rather than hidden from her family — experts say they can see a type of rejection and disregard in her experiences.

Sonia Smith-Kang, president of the Multiracial Americans of Southern California, said she hears interracial couples and family members describe their own experiences being “othered” by family.

“A lot of it is microaggressions,” she said. “It’s everything that Meghan talked about, from colorism to phenotype, and asking those kinds of questions. That can lead to feelings of isolation.”

Smith-Kang is of Black and Mexican heritage, and she has four kids with her husband, Richard, who is of Korean descent. She said conversations about racial identity, white supremacy and implicit bias are especially important when it comes to raising multiracial kids.

Sylvie Vaught, 49, said the early days of her relationship with her husband, Kelly, were smooth sailing. They were childhood friends who reconnected in adulthood, and it immediately clicked.

“Everything flowed,” she said. “There wasn't too much apprehension at that point, and I related to Meghan in that way.”

Vaught is of Black, white and Native heritage, and her husband is white. She had dealt with the dinner table comments and implicit bias. “Oh, you don't mind if I tell a Black joke, do you?” one of her husband’s relatives once asked her. But the racism worsened once they brought their newborn daughter home from the hospital in 1998.

“My husband's grandmother comes up to my husband, and he's holding our daughter, a new little baby, and she looks at the baby and she goes, ‘Oh, wow, I guess you got your little N-word baby, don’t you,’” Vaught said.

Vaught wasn’t in the room when it happened, but she was shocked when he told her about it later. He previously warned her that there was “some racism in that part of the family,” but she didn’t have to interact with them very often.

“Especially that time period, and up until pretty recently, I feel like people just kind of accepted it,” she said. “Like, ‘Oh, yeah, this person in the family is racist’ or ‘that's just the way they are,’ and there's no calling them out too much.”

These experiences played in her head as she watched the Meghan and Harry interview. It’s exhausting, she said, to always feel like the other.

“I felt really sad,” she said. “You know what, I'm tired of this. You just have this feeling like, is this ever going to be worked out? Are we always going to have to deal with this?”

Gretchen Heidemann, 43, met her husband online in 2008, “before swiping was a thing.” The first time she met his mom, she warned Heidemann that her son was “not the marrying type.” Pretty soon after that, they were engaged. Heidemann’s family is from a small, white town in rural Ohio, “Like red, MAGA, Trump country,” she said.

She grew up close to her only living grandmother, who had never seen a world outside of her town and often made racist comments. At lunch one day with her sister, her grandma asked her if she was dating someone. She said she had a “sinking feeling in the pit of my stomach.”

“So, tell me, is he tall, dark and handsome?” her grandma asked her.

“And I said, ‘Well, he's not especially tall, just kind of standard height. Very, very handsome and, yes, his skin tone is dark. He's a Black man,’” she said. “And she just like, froze. She looked p----d.”

For the next several months, Heidemann said there was a silent tension. She lost contact with her grandmother for a long time before many heated conversations finally came to a head and she demanded respect for herself and her partner.

“A couple months later, I got a letter in the mail from her saying, ‘I'm so sorry,’” she said. After meeting for the first time, Heidemann’s husband and grandmother actually grew close. He was the last person she talked to on the phone before she died. But Heidemann said her hometown doesn’t feel like a safe place for her family anymore, especially now that she has a 4-year-old daughter.

When kids are involved, the conversations become especially important, Smith-Kang said. Visibility for multiracial children can only happen when their parents are willing to be open with not only them, but also with each other. Meghan and Harry's revelation illustrates the "deep awareness and understanding" around race and discrimination that often must come with being married to someone of a different race.

For other multiracial couples, early conversations about white privilege, systemic racism and racial identity are not just healthy, but also necessary.

“I think folks feel like love will conquer all,” she said. “But as couples and as parents, we need to help that along.”

Related:

This story first appeared on NBCNews.com.