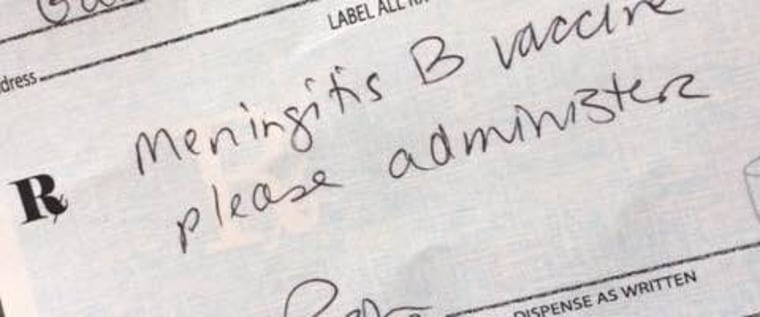

It was such a tiny vial of fluid — only .5ml of clear and glistening liquid inside a syringe topped with the finest of needles.

I stared at it with wonder. I wanted to ask if I could hold it but knew it would seem like a strange request to the pharmacist who didn’t know the truth I carried that day.

It was the vaccine that could have saved the life of my firstborn child.

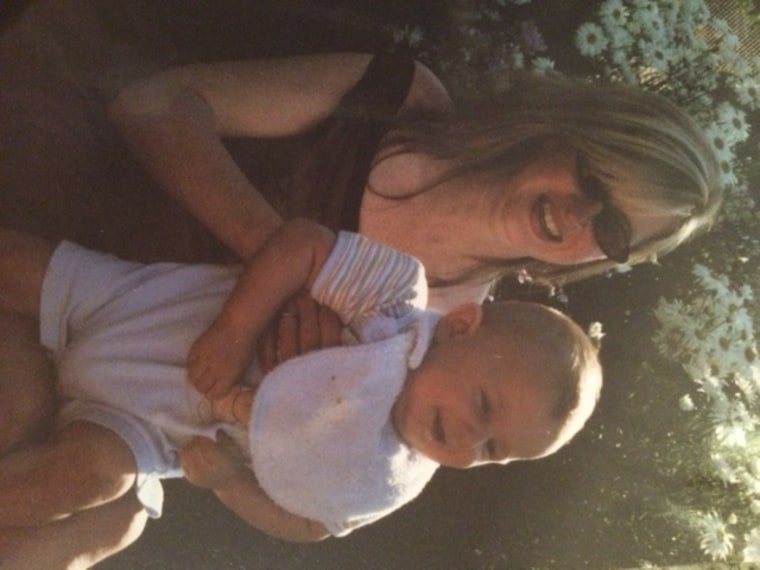

He was 7 months and 4 days old when he died in 2005 of meningococcal serogroup B, a rare but devastating disease. At the time, there wasn’t a vaccine approved for use in the United States. In fact, there wasn’t until 2014 when the FDA approved it after a cluster of outbreaks among college students.

Now, there it was — the elixir I had hoped would be possible in my lifetime, sitting on the pharmacist’s desk on a sunny Friday afternoon.

“What brings you here?” she asked my 9-year-old son and me.

Related story: When a name is all that's left — why I changed my name to honor my son

“My brother,” my son answered. He was born a year and a half after his brother died, but he knows him through photos and the stories we tell. And he knew the significance of the vaccine he was getting. Since it had been approved for use here, he’d been asking when he’d be old enough to get it. While it’s offered to babies as young as 2 months in places like the UK, it’s still usually only generally recommended for those 10 and older in the U.S. Our pediatrician, who also helped care for our first son, allowed him to get it a few months early.

I held him in my lap as he got the first of the two-course series of shots. “That was it?” he asked as soon as it was over.

That was it. A quick injection and you get to live.

Never miss a TODAY Parents story with our newsletters: Sign up here

It’s impossibly simple. But the topic of vaccination is also impossibly heated, divisive and politicized. In fact, as I’m telling this story now, I’m leaving out the names of my two boys because when I’ve been public about this issue in the past I’ve sometimes been met with fierce anger. Their names are the most beautiful to me in the world and I want to protect them, even my son who is gone. You don’t lose that instinct when your child dies.

I don’t want any other parent to ever know what I know now. I don’t want anyone else to feel what it is like to watch your child die, 12 hours after his first symptom that anything at all was wrong. I don’t want any other parent to understand what it’s like to still ache for just one more kiss on that softest cheek, even 11 years later.

We are into the new school year, a time when kids are getting back-to-school shots — or their parents are working on exemption letters. Some communities in Washington state, where I live, have some of the highest rates in the country of parents opting out of vaccines for their kids for medical, religious or philosophical reasons. A new study published in the journal Pediatrics showed that a rising number of pediatricians have been asked by parents about skipping vaccines or delaying them. We’ve also seen a resurgence of whooping cough and other vaccine-preventable diseases. In the recent years, measles, once eradicated in this country, has reappeared, causing the first confirmed measles death in a dozen years in 2015.

I know there is skepticism about vaccines. I know not all vaccines are perfect. But there is no ambiguity for me — or for the many who loved my firstborn. None of us exist in a vacuum. Our lives touch a constellation of others. Children are at the heart of that galaxy and when one dies, that loss echoes out infinitely across time. It interrupts the order of the universe. It stops the future.

Related: What not to say to a grieving parent, and what actually helps

In the book “A Broken Heart Still Beats,” bereaved parents Anne McCracken and Mary Semel recount a parable about a man who goes to a philosopher to ask for a blessing for his family. The philosopher tells him, “Grandfather dies. Father dies. Son dies.” When the man asked what kind of a blessing that was, the philosopher replied, “What other way would you have it?”

A few days after my son got his meningitis B vaccine, we buried his beloved Grandma Pat, my husband’s mom. She was a crucial part of the bedrock of our extended family. Both she and my mother, both somewhat shy but devoted advocates for the children they loved, along his grandfather, had attended public meetings and spoken out about the need for vaccines. They had seen what happens when the order of the universe is upset. They had each stood in their first grandson’s hospital room the day he died and held his body as the sun set.

What they wanted most — what I want and any of us want — is for our children to grow up strong, happy and healthy. We desperately want our children and grandchildren to outlive us. Vaccination is one of the best ways now we have of battling these diseases that once gutted families. Many of us don’t remember that time, but the generations before us do. Vaccination is a modern marvel of our time, but it’s also something that now we have the luxury of taking for granted. We shouldn’t.

In the pharmacist’s office, as I looked at the syringe with the vaccine, I found it stunning that something so simple could have made the difference between life and death. I almost wanted it to be bigger or more complicated in some way. The vaccine was too late for one of my sons. But it was in time for my other. As with so many things in life, the joy is balanced with the pain.

Linda Dahlstrom Anderson is an editor and writer based in Seattle. Her work has appeared on TODAY.com, NBCNews.com, Mashable and other news outlets. Follow her on Twitter: @Linda_Dahlstrom