Every fall, a new crop of high school seniors stresses over the personal statements, SAT scores and extracurricular activities that'll help them get into the college of their dreams. And this fall is no different. Well, a new survey of recent college grads by Jacques Steinberg, of “The New York Times Magazine,” suggests that students and their parents can just take a step back and relax.

Laurie Hoachlander's parents may have spent tens of thousands of dollars on the psychology courses she took as an undergraduate at the University of Pennsylvania, but ask the 27-year-old, a member of the class of 2002, what was most valuable about her college years, and her thoughts drift far beyond the classroom window.

There was her year as a resident adviser to a cluster of freshmen in her dormitory at Penn, an experience colored by the attempted suicide of one of her charges, followed by his recovery and return to the hall. ‘‘That taught me a lot about crisis management,’’ she says. Then there was her work as a campus tour guide, which taught her ‘‘how to be a better public speaker.’’ That, she says, wound up serving her well in one of her first jobs, as a leader of seminars for real estate brokers: They would interrupt her presentations with offbeat questions, just like the pesky parents on her tours.

As high-school juniors and seniors descend this fall on fact-finding missions to the nation’s colleges and universities — an indispensable part of the uniquely American hazing known as the college-admissions process — a fresh cast of cheerful student tour guides will steer the conversation through familiar scripts. They’ll dutifully note the number of volumes in the library and the opportunities for undergraduate research and the ratio of professors to students. Only the most persistent of pesky parents will draw out a story like Hoachlander’s of a moment in college life that really made a difference; arguably, it’s the rare undergraduate who has the perspective to recognize that moment, let alone go off script to recount it.

But talk to a couple of thousand recent college graduates, as the magazine did this summer — alumni roughly five years out of school, with the perspective that comes from having got a taste of the real world but with memories of freshman and sophomore years still relatively intact — and enough moments spill out to begin to tell a story. Some graduates fondly recall a special professor, others the opportunity to become more self-sufficient. Some say they didn’t study hard enough; others, though fewer, regret working themselves too hard and wish they’d taken more time to relax or learn about life from their peers. Yet overall, the story told by these survivors of the admissions process is actually pretty simple: College is great. And their message to those coming up behind them — the classes of 2012 and 2013 and 2014, bigger than any generation of college prospects before them and as anxious as their parents are hovering — is pretty simple, too: Chill out.

To an astonishing degree, recent graduates surveyed by The New York Times Poll said that they are satisfied with the choices they made about where to go to college and with the education they received. That seems to hold true whether they went to big schools or small schools, costly private colleges or somewhat more affordable public universities, their first-choice school or their fourth. Like Laurie Hoachlander, though, the young alums acknowledge, in a variety of their responses, that the qualities they or their parents thought were crucial in choosing a college were not necessarily the things that mattered most once they got there. Magazine rankings and a school’s reputation — both extremely important in the minds of many applicants — are often of far less significance to graduates as they reflect on what made their college years worthwhile.

‘‘Now I value the goofy and formative life experiences — driving to Atlantic City on a whim, playing a weekly basketball game with my friends, playing pranks in the dining hall,’’ wrote Dan Diamond, a newsletter editor who was a classmate of Hoachlander’s in the class of 2002 at Penn.

So “The New York Times” conducted a series of surveys over the summer. Telephone polling in conjunction with mtvU, the music channel’s on-campus network, produced a sample of 271 college graduates under age 30. (The nationwide poll, conducted June 15 to June 23, has a margin of sampling error of plus or minus 6 percentage points.) Separately, online surveys by The Times gathered the replies of more than 1,300 graduates, most in the class of 2002, from three institutions generally regarded as among the finest and most selective in the nation: Penn, an Ivy League university in Philadelphia; Reed College, a small liberal arts school in Portland, Ore.; and the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, a state university. I called a dozen alumni afterward to probe more deeply into their responses to the poll questions.

Much of what the polling found falls safely into the category of ‘‘reassuring’’ — not an adjective that tends to be associated with the college search. Among the group surveyed nationally, 93 percent described their overall undergraduate experience as ‘‘excellent’’ or ‘‘good’’; the results were comparable for the alumni of Penn (95 percent), Michigan (96 percent) and Reed (98 percent). Likewise, asked if their college education ‘‘was worth the money you and your parents paid for it,’’ 89 percent in the national poll said that it was. At Reed and Penn, where tuition bills are among the highest in the nation, 81 percent and 79 percent, respectively, said they got their money’s worth. (At Michigan, where tuition is lower for state residents, 84 percent of alumni agreed.) To plumb whether that learning served any practical purpose, those alumni who said they had jobs were asked whether their undergraduate education ‘‘prepared you for the work you are currently doing.’’ Seventy-five percent in the national poll said yes — very nearly as positive a response as among the graduates of Penn (82 percent), Michigan (83 percent) and Reed (86 percent.)

(The upbeat responses from alumni of those three colleges come with a caveat: The graduates surveyed chose to be in close-enough touch with their alma mater to at least supply an e-mail address where they could be reached. But their answers were similar enough to those of participants in the national poll — who were part of a random sample — to suggest confidence in the results all around.)

Of course, a high school student staring at a blank college application may be most interested in the answer to the following question: Why? What made these individuals’ college experiences so good? Why was it worth the angst and the hard work and — their parents would probably also want to know — the lingering debts?

For the Penn and Michigan graduates in particular, the answers are not always what they expected back when they were writing essays and filling in SAT bubbles. They recalled being extremely focused on their schools’ brand names: Of the Penn alums, 88 percent said that reputation was ‘‘very’’ important when they were deciding which school to attend, as did 78 percent of the Michigan alums. Similarly, 85 percent of the Penn graduates and 72 percent of the Michigan grads said that their university’s ranking by “U.S. News & World Report” was ‘‘somewhat’’ or ‘‘very’’ important when they were making that decision.

Yet five years after graduating, about one-third at each university said that the rankings seemed ‘‘less important’’ to them now than they did in high school. Asked to volunteer what they valued most about their college experience, 10 percent of the Penn alums — and 5 percent of the Michigan graduates — mentioned their alma mater’s reputation. Graduates of both universities were more likely to cite the friendships they made at school. The responses suggest that the critics of college lists are on to something; maybe the devaluing of the rankings can serve as a tonic to the unrelenting obsession they foster among many applicants and their parents.

The Reed alumni teach a different lesson. Reed has long stood opposed to the very idea of college rankings, electing not to provide data to “U.S. News,” so students in the yearly classes of 300 or so freshman start out picking the school for what it stands for rather than where it stands. And the graduates, looking back, seem to reaffirm the notion that students following their instincts can find their way to the right school. As if parroting the marketing copy in the college’s brochure, alums overwhelmingly endorse Reed’s ‘‘conference’’ style of learning, in which lessons transmitted in lectures are later reinforced in smaller groups where students engage in spirited debates. Twenty-eight percent of the respondents from Reed said that learning ‘‘how to think, to work, to learn’’ in college was what they valued most now. Another 27 percent cited research skills or other kinds of training.

One was Andrew Schpak, 27, a litigator in Portland who graduated in 2001. He said the school’s emphasis on Socratic learning was perhaps as valuable as anything he learned at Cornell law school in preparing him to argue before judges, juries and opposing lawyers. ‘‘Reed taught me to think on my feet, to think beyond my gut reaction and to think about what might make me change my mind,’’ he told me in a follow-up interview.

One conclusion to be drawn from Andrew’s obvious satisfaction with his education, when laid alongside the responses of so many of his peers, is that the convoluted process of matching students to colleges ultimately does what it is supposed to do. But in the end, I also find myself reflecting on the ongoing regrets expressed by so many of the alumni we contacted — not with their overall college experiences but with the day-to-day choices they made, whether it was the belly-dancing class that one Reed graduate said she missed out on because she was studying too hard or the Greek tragedy that lay untouched on another Reed student’s dorm-room bookshelf and now, in all likelihood, will never be opened.

Perhaps we should be spending a little less time coaching and cajoling high school students about how to get into college, or even how to identify that mythical ‘‘right’’ college, and instead help them prepare a little better for how to strike a balance, or explore what they hope to accomplish, once they get there.

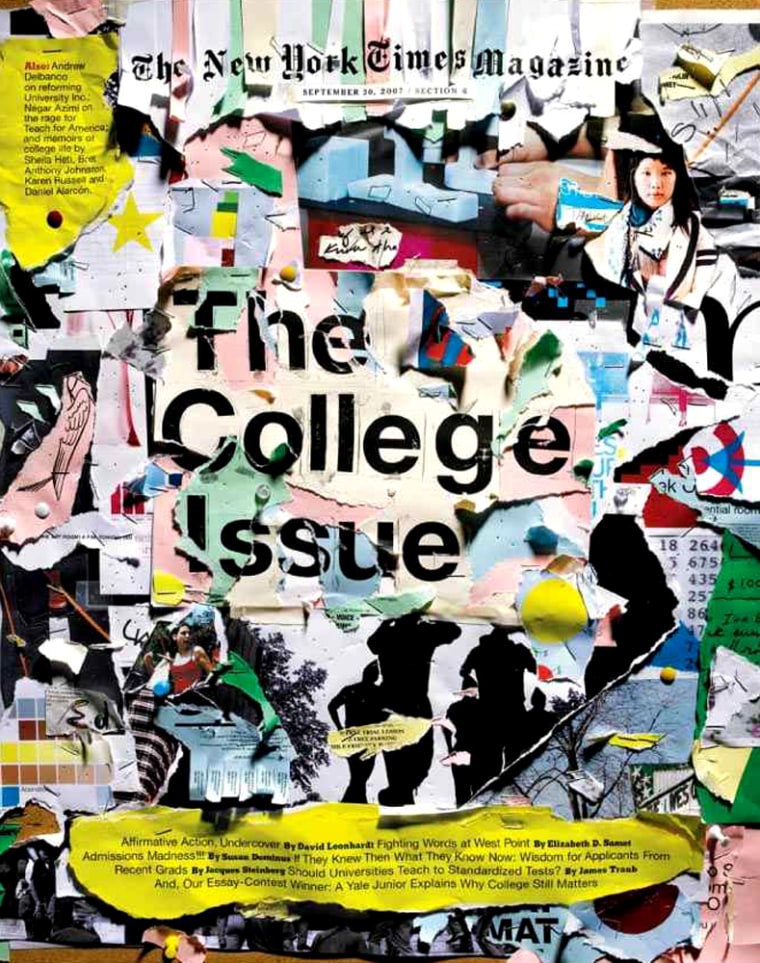

For more information on “The New York Times Magazine” special college issue, visit