Oh yes, there's a "Big Mayo," and he's trying to squeeze the little guy.

Mayonnaise is the top selling condiment in America, as mentioned in story after story this week about Hellmann's lawsuit claiming false advertising and fraud by a vegan startup. Per FDA regulations, "mayonnaise" is supposed to contain eggs. "Just Mayo,” made by Hampton Creek and on sale at Wal-Mart, Whole Foods and Dollar Tree instead uses yellow peas. Its label features a white egg cracked by a pea shoot.

You can understand why Hellmann's would see red over its white stuff. There was nearly $2 billion in mayo sales in 2013, according to an analysis by Euromonitor, a market research group.

What's less understandable is how mayo beats both ketchup and salsa (which is technically a “dip” not a condiment), neither of which broke a billion.

The numbers don’t lie. You love mayo.

This is despite the fact that many people totally hate mayo.

Mayo loathers accuse it of having a “slimy” texture, calling it “fatty” and “tasteless.” There are Facebook groups, T-shirts and websites dedicated to stopping mayo.

“The smell, the consistency, the fact that it came from raw eggs, well, it's stomach-turning,” said Craig Horwitz, founder of holdthatmayo.com.

But mayo lovers demur.

"Mayonnaise is a simple, yet elegant way to add tang, richness, and a creamy mouthfeel to almost any savory food," said Elizabeth Valleau, co-founder of Empire Mayo, a Brooklyn store dedicated solely to selling gourmet mayonnaise.

Considering how divisive mayo is, it seems unlikely that it should become America’s No. 1 condiment.

But it had to. Mayo is America's king of condiments because it tastes like America. It glues together disparate flavors and textures into a more pleasing and palatable homogeneity.

"The fattiness of mayonnaise makes it a tremendous flavor binder and enhancer," said Valleau.

Maybe instead of "The Great Melting Pot" we should call ourselves "The Great Emulsification Bowl."

It's hard to imagine most sandwiches, or a church potluck or picnic, without mayo. It's found in innumerable American recipes from potato salad, to tuna salad, to macaroni, slaw, deviled eggs and even in some baking.

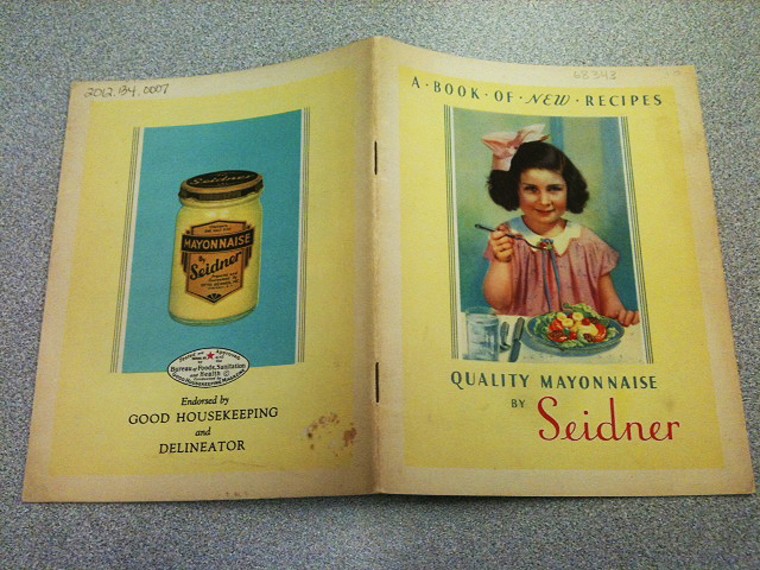

Part of the reason that so many dishes contain mayonnaise is that starting in the late 20s and 30s Hellmann's was an absolute machine when it came to marketing recipe books that promoted the use of mayo.

Hellmann's was the company that brought mayo to the masses. In the 18th century, mayo was a foodstuff of elite Europeans. The mix of oil, vinegar and raw eggs, called an emulsion, had the tendency to separate back into its parts. Because of the eggs, it only lasted three to four days. Even by the turn of the 20th century it was still considered a labor-intensive and effervescent luxury.

Then Hellmann's "weaponized" mayo. Starting out of a small deli in New York, Hellmann's joined with other mayo makers in using a pasteurization process to turn it into a commercial product with a shelf life. Developing and adding industrial production, distribution and marketing, the company became a national business.

But capitalist prowess alone didn't make mayo mighty. The thick white spread solved a problem. With mayo, you could take the trimmings from a 20-cent sliced chicken sandwich and turn what would have been waste into a chicken salad sandwich and sell it for 10 cents. It was bootstrapping on toast.

From lunch counters to Sunday potlucks, chefs learned to rely on their little jars with the blue ribbon on the front. It was quite handy. "You can use it to brighten up and add taste to something," said Richard Gutman, curator of the Culinary Arts Museum of Johnson and Wales University in Providence, R.I.

All the while, Hellmann's and other mayo makers kept stoking demand by inventing and promoting new recipes that they inserted into magazines, advertising and cookbooks. Colorful illustrations showed how you could take a few simple ingredients, add a cup of mayo and spices, and have a bite of the good life.

One historic booklet in Gutman's archives described 160 recipes for using it in combination with JELL-O. Another detailed a peanut butter and olive sandwich with mayo beaten into the peanut butter.

If not always delicious, mayo certainly spurred innovation.

Culinary historian Andrew Smith has studied historic menus from church luncheons and Sunday afternoon dinners. For over 150 years, potato salad has been on those menus.

"It's cheap. Potatoes cost nothing. Mayo costs nothing. Eggs and seasoning cost nothing," said Smith.

Add a teaspoon of chili sauce to mayonnaise and slather it on some asparagus, said Gutman, and mayo "makes you think you're putting on a fancier party."

As mayo grew in popularity, national brands set the standard for flavor and ingredients and had the resources to comply with federal regulation. Before food and drug safety legislation gave the federal government the power to sue shady food manufacturers, unscrupulous mayo makers would put white paint into mayo to make it whiter, or plaster of Paris into milk to pass it off as mayo.

No one is suggesting any such shenanigans in the current lawsuit. But Hellmann's still finds itself asking the government to crack down on its upstart rival.

"We are a strong supporter of innovation both within and outside our company," Unilever, Hellmann's corporate parent, said in a statement. "Our concern here is not about innovation, it is about misleading labeling as it is not accurate to label the Hampton Creek product as 'Mayo' or to reinforce the link with images of ingredients, in this case eggs, that are not even used. In contrast, our Hellmann's brand is made from real eggs. We simply wish to protect both consumers from being misled and also our brand.”

In reply, just look at the Romans, said Josh Tetrick, CEO of Hampton Creek, makers of Just Mayo. It's only relatively recently in culinary history that the flavorful spread has required eggs. He said his team's research uncovered a 77 AD Roman recipe for a "garlicky aioli" that emulsified olive oil into a paste mixed with garlic.

Tetrick says its time we start rethinking the regulatory framework around mayonnaise and other foods.

"The standard of identity was written a number of decades ago," he said. "We do call our product 'mayo' for a reason. We do believe it keeps us on the right side of the standard of identity."

As a food business disrupter seeking to make healthier more flavorful foods that are cheaper and have lower environmental impact, his company went after mayo precisely because it was the No. 1 selling condiment in the country and ripe for a revamp.

"The reason why it's so American is it goes on top of and inside so many American things," said Tetrick. "It's Fourth of July and it's on a hamburger. It's on a BLT. It's on your grandma's chicken egg salad. It's on her chicken salad. Tuna salad. It's on Thanksgiving leftovers. When you have these iconic American things, mayo is there."

Email Ben Popken at ben.popken@nbcuni.com or tweet @bpopken.