It’s difficult enough for most parents to talk to their kids about the birds and the bees. But that often dreaded discussion brings a whole new set of challenges for couples who have conceived with the help of test-tube technology.

A key to success, experts say, is to keep the conversation honest, open and age-appropriate.

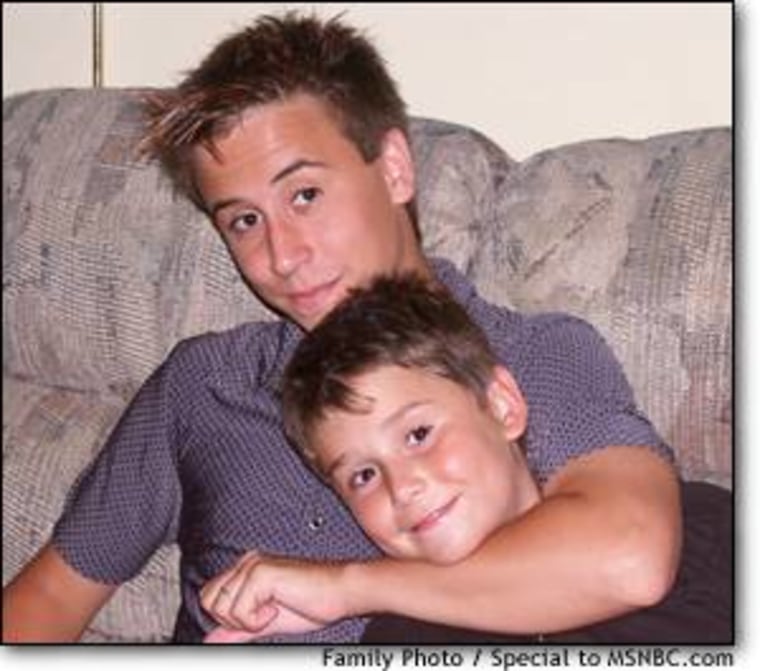

Tyler and Spencer Madsen, ages 15 and 10, don’t remember much about the time their parents first told them they were conceived through in vitro fertilization, or IVF, an infertility technique in which their mother’s eggs and father’s sperm were mixed in a lab dish.

Their mother, Pamela Madsen, says that during their preschool years the boys started asking questions about where babies come from. So she used the opportunity to launch a truthful — but simple — discussion.

“I didn’t take out a chalkboard and draw a diagram,” she says.

Rather, she discussed how mommy and daddy loved each other and needed some help from a doctor to have a baby.

“I never gave them more than they asked,” says Madsen, founder and executive director of the , a patient support group.

Don't go overboard

When the boys turned 8, she gave them a more detailed description of IVF. And the discussions have continued to become more sophisticated over time.

But some parents who are disclosing to their kids that they were conceived through IVF or other forms of assisted reproductive technology, or ART, may have a tendency to go overboard, providing too much complex information too soon.

“I think sometimes we’re telling more than kids want to hear,” says Madsen. “You really have to listen to the question.”

If young children ask where they came from, for instance, do they want to know the birds and the bees or simply the city they were born in?

No one specific age of a child is best for those first discussions of ART, experts say, but they generally recommend that an age-appropriate dialogue begin earlier rather than later.

One of the concerns is that the child will find out from someone else, raising trust issues with the parents. And hearing the news for the first time as an adolescent may be particularly difficult for a teen who’s already wrestling with typical identity issues.

To tell or not to tell

While there are no solid statistics on how many parents of ART kids choose to tell them the specifics about their origins, insiders say it’s not uncommon for couples to remain silent.

“We believe in disclosure,” Madsen says. “But some people have their own private reasons for not wanting to disclose. And I don’t try to make judgments about that.”

The decision may depend on how the child was conceived. In cases where an egg, sperm or embryo came from a donor, for instance, therapists generally recommend disclosure on the grounds that children have a right to know about their genetic parents and should have access to available information about their family medical history.

But there’s some disagreement about whether kids conceived through straight IVF — involving the egg and sperm of the people who will raise the child — should be told.

“If both of the adults are the genetic parents of the child, I really don’t see disclosure as an issue at all,” says Anne Bernstein, an assistant clinical professor of psychology at the University of California at Berkeley and a research associate at the Council on Contemporary Families, a group that addresses issues facing American families.

“I don’t think it makes any real difference in their lives if medical assistance was necessary for fertility,” she says.

Secrets can be risky

Others, however, note that while most evidence regarding the safety of ART procedures is reassuring, long-term safety studies aren’t available yet and these kids may one day need to know aspects of how they were conceived, such as what exactly was in the culture medium that bathed the embryo in the lab or what drugs the mother took to try to conceive.

“It’s a part of their medical history,” Madsen says.

Furthermore, experts caution, secrets can be risky.

“I think that children sense secrets and always feel that secrets are bad,” says Patricia Mendell, a psychotherapist with a private practice in New York City and director of support hotline services at the AIA.

Lee Collins, a mother of two daughters, Victoria, 7, who was conceived the old-fashioned way, and Nina, 3, who was conceived through IVF, says it would have been difficult to hide details of Nina’s conception.

Victoria witnessed all the hormone injections her mother took as part of two years of infertility treatment before becoming pregnant with Nina.

At one point Collins suffered a miscarriage, and the overwhelming sadness felt by her and her husband was easily detected by Victoria. Collins consulted a child psychologist to come up with language that she says worked well: “We thought a new baby was going to come to our house but it didn’t and now I’m sad.”

Coping with infertility was a big event, Collins says, and one she didn’t see a reason to try to conceal.

“It’s part of our story now,” says Collins, a member of the board of directors of , another support group for people dealing with infertility. “We simply couldn’t tell our family story without telling how Nina was conceived.”

How kids take the news

Experts in the fertility field say ART kids, just like most other youngsters, love to hear about where they came from — and they often handle the news better than parents might expect.

“I think the negative reactions come when children feel like they’ve been lied to or deceived in some way, and omission of information can be a kind of deceit,” Bernstein says.

As with adopted children, some ART kids conceived with the help of donors will express interest in finding out more about their genetic parents, even meeting them. But that may not be possible since many donation programs are anonymous.

“I am a strong advocate of a ‘knowable’ donor,” Bernstein says, so that the kids can find out more about their genetic parent and possibly even meet them one day, if they want to.

The Madsen boys say they don’t see their conception as anything that regularly affects their life, except in one way. As part of events organized by the AIA, they sometimes speak to groups of doctors and other health-care professionals about what it’s like to be an IVF kid and whether they feel any different.

“It’s not like I have superpowers or anything,” Spencer says. “But I wish I did.”

He’s grateful for fertility techniques nonetheless.

“I was lucky that IVF was there for my mom to have me,” he says.