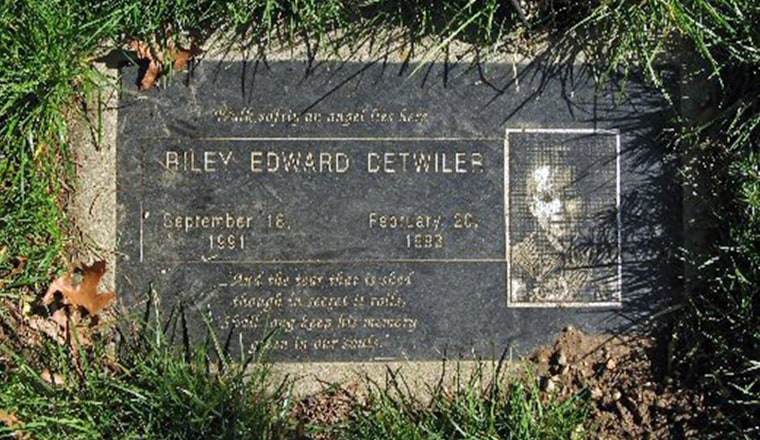

Darin Detwiler’s son Riley was a healthy, thriving 16-month-old when he died of E. coli poisoning in February 1993. The toddler was one of four children who died during a multi-state outbreak of E. coli traced back to contaminated hamburgers sold by a restaurant chain. Detwiler spent the next 30 years raising awareness about food safety, fighting to stop foodborne disease and pushing for reform. He shared Riley’s story and his perspective on the current state of food safety with TODAY.com.

Riley had never eaten a hamburger. He got sick from another kid in his daycare, but no one was talking about person-to-person exposure. No one knew what E. coli was in 1993.

In January, there had been news in Washington State about an outbreak tied to hamburgers. So Riley’s mom and I thought, "Let’s just avoid going to fast food hamburger places and we’ll be fine."

I go to my son’s daycare one day to pick him up and there’s a notice on the door that says another child in this daycare facility has tested positive for E. coli and to look for symptoms. We saw those symptoms in Riley that night — his urine was a different color and there was some bloody stool — and freaked out.

I later learned the other child’s parents both worked at the fast food restaurant. The mom cooked a hamburger for herself and her 18-month-old kid at a temperature that was too low to kill the pathogen. The other child had bloody diarrhea, which leaked out of the diaper at the daycare center. My son got sick from person-to person-contact with this other kid.

Zero chance of recovery

Back in 1993, it took 48 hours for E. coli test results to come back. When Riley’s came back as positive, he had not improved. He was admitted to the local hospital in Bellingham, Washington, and then airlifted to a hospital in Seattle.

His symptoms were getting worse and worse. With severe E. coli, you can develop hemolytic uremic syndrome and that ravaged his intestines. Doctors had to remove a large percentage of his lower intestines that were completely damaged.

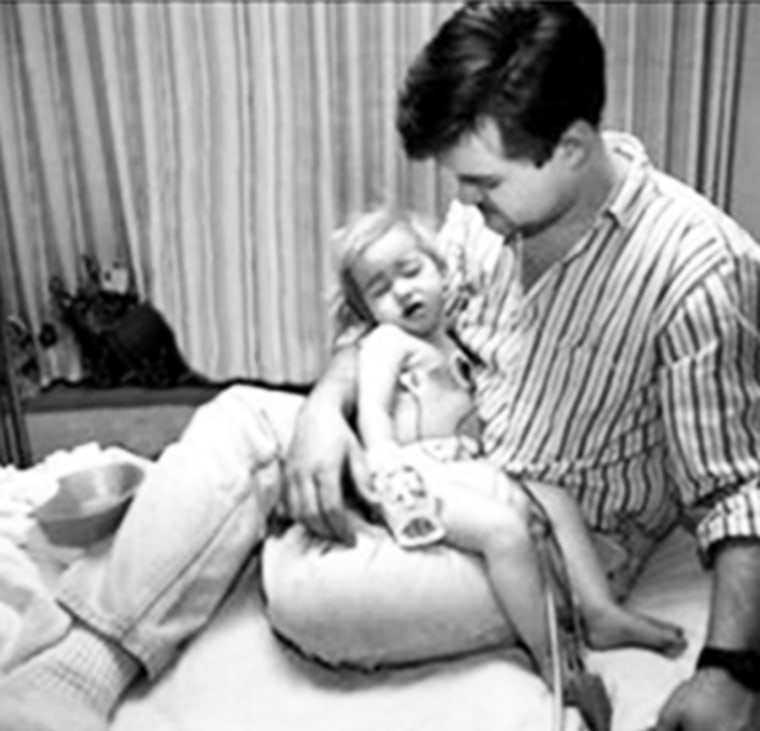

In the beginning, I was able to hold Riley on my lap. I remember him looking at his IV bag, pointing to it and saying “ba ba” like it was a bottle. I realized that was him wanting comfort and normalcy.

Later, he was in a medically-induced coma and it was just a matter of two to three weeks of watching him continue to deteriorate. He had so many wires, tubes and monitors that he was almost dwarfed by all of this equipment keeping him alive.

You’re thinking: Of course he’s going to recover from this. How do people die from this? He’ll get better and I’ll be able to tell him how proud I am of how he survived.

But doctors said there was zero chance of recovery, and even if there was recovery, he would be brain dead. He had so many organ failures.

Riley was taken off life support and placed into my arms. I got to hold him again, but it would be the last time. He died on February 20, 1993. The other child who had E. coli in Riley’s daycare was never even hospitalized. I’m glad — you can’t blame an 18-month-old.

'What happened to my son still happens today'

After Riley’s death, I talked to President Clinton on the phone. I said, "I can’t sit by and not do something about this. I still need to be a father to my son. We need to make E.coli a household name."

I talked with television shows, I wrote articles, I did a ton of work to make this known. I worked with the USDA to put out information around food safety. Today, E. coli is a household name, as is salmonella and listeria.

Between now and 30 years ago, we saw a significant decrease in contamination tied to meat and poultry. But we saw an increase in outbreaks in ready-to-eat foods, produce, romaine lettuce and leafy greens. People are getting sick from sprouts, cantaloupe and other food.

I used to avoid eating red meat after my son’s death, but I realized that if I were to avoid eating everything that’s ever been identified as a culprit food in terms of foodborne illness, there’d be nothing left to eat. It’s just incredible how pervasive foodborne pathogens are in our food supply and how much responsibility is placed on the consumer in terms of proper handling and cooking.

What happened to my son 30 years ago still happens today. I talk with families who buried children from E. coli, salmonella or listeria all the time.

The No. 1 mistake I see people make is a blanket assumption that food is always safe. I don’t want to make people afraid, but there needs to be a better priority put on the idea that food comes with risks. We need to cook it properly, put things in the refrigerator and wash our hands.

Having a raw piece of steak or hamburger does not make you more manly or more American. If you want to do that as a healthy adult in your own house, great. But if you’re in a house with a pregnant woman, young child or an elderly grandparent, you’ve got to realize these are vulnerable populations. They are much more likely to end up in the hospital and dead because of a foodborne pathogen.

When I go into a restaurant and the bathroom is dirty, I don’t even want to know what the kitchen looks like. I look to see if people are cleaning tables, going on a break, taking trash out, smoking and then handling food without washing their hands.

I don’t go to buffets because I think about the holding temperature of the food and how many people come into contact with that food over time.

My mission is to prevent another family from living with a chair forever empty at the family table.

Thirty years ago, I said, “This is 1993. This is the United States of America. How can this be happening?” And just recently, I heard a mother whose daughter was barely hanging on at a children’s hospital say, “It’s 2022. This is United States of America. How can this be happening?”

It brought up this déjà vu in terms of how many families are going through this incredibly tragic moment caused by mostly preventable failures in food safety.