In February, Angela Ellis was watching TV on her couch when she felt a lump in her left breast. Soon after, she visited a doctor and underwent an ultrasound and mammogram, which confirmed there was a mass.

But at a follow-up appointment with a breast surgeon, the doctor told her the lump was harmless.

“He did a breast exam and was like, ‘Yeah, I’m not worried about this at all. This is 99.99% ... a benign mass. If you’d like, I can just leave it in there,’” Ellis, 27, a medical student at the Philadelphia College of Osteopathic Medicine, tells TODAY.com.

Still, Ellis scheduled surgery to have it removed.

After the procedure, she didn’t hear from the doctor and received an alert from the electronic medical records system that revealed the mass was not benign.

“It said, 'Invasive ductal carcinoma, ER negative, PR negative, HER2 negative,' which means I have triple-negative breast cancer, which is a more aggressive breast cancer,” she says. “I had an idea of what it said because I was learning about it in medical school.”

A lump eventually leads to a diagnosis

While Ellis watched TV, wrapped in a blanket, she was leaning oddly and felt something hard in her breast. She moved the blanket and still felt the lump and then compared her left and right breasts. The spot was only in her left breast.

“I was like, ‘Oh, that’s weird,’” she recalls.

She visited her OB-GYN and was recommended to get an ultrasound and mammogram. At first, she thought she’d only get an ultrasound because she didn’t have a family history of breast cancer. But during the appointment, the technician called in the radiologist, who suggested completing the mammogram that day, too.

The screenings both found the mass, so a week later, she saw a local breast surgeon, even though previous doctors told her it was likely benign. She hoped the breast surgeon would put her fears to rest and confirm the cyst wasn't cancerous. After he performed a breast exam, he told her that she didn’t need to do anything.

“He’s like, ‘You can leave it in, or we can take it out. But you’re a medical student, so why don’t you come back in three months? We can worry about it after you take your board exam,’” she recalls. “I was like, ‘Really?'"

Ellis says the doctor responded by telling her about another patient with a fibroadenoma, a noncancerous breast tumor common in young women, who went backpacking for three months and was fine when it was removed after her trip.

She felt reassured, but after speaking with her parents, she decided to have it removed sooner instead of waiting.

“My mom actually was the one who was like, ‘I don’t know. I wouldn’t mess around with it. Just get it out,’” Ellis says.

Ellis called the doctor to schedule surgery to have it removed.

“I was like, ‘Look, I know you said that I can wait on this, but I would rather not worry about it,’” Ellis says.

She underwent surgery on a Thursday and was told someone would call soon after to inform her whether the mass was cancerous. She didn't hear anything until Monday, when she received a notification about her pathology report from her patient portal.

She opened it, expecting to read that she had a fibroadenoma, as the surgeon had told her he wasn't worried. But “I read the total opposite," Ellis says. "(The doctor) never even told me I had cancer."

At first, she thought it was a mistake and called the doctor.

“The first thing he said was, 'I guess you saw the test results,' and I was like, ‘Yeah, I saw the test results. Were you ever going to call me and tell me I have cancer?’” Ellis recalls. "He was like, ‘I didn’t know what your med school schedule was like.'"

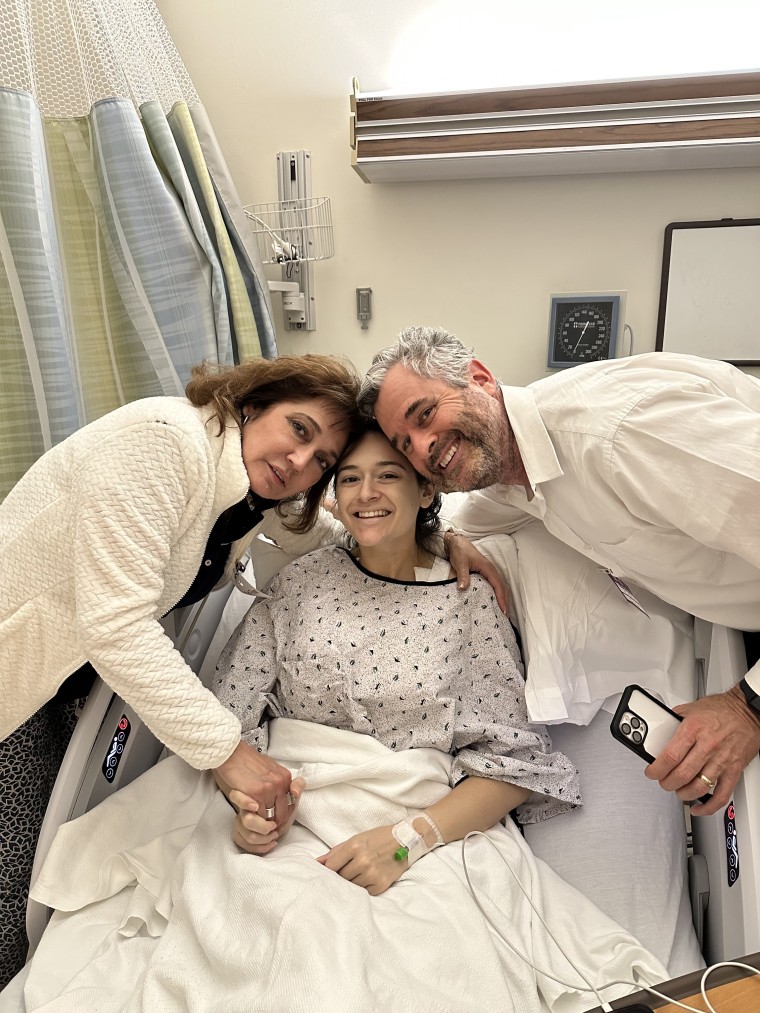

She felt stunned and upset. The doctor provided treatment options, but Ellis felt overwhelmed. She needed time to process the diagnosis and speak with her loved ones. After a few days, Ellis knew she wanted a second opinion.

“If I listened to (his) advice to begin with … I could have been looking at a much different outcome,” she says.

She met with an expert at Fox Chase Cancer Center in Philadelphia to learn more about her treatment options. Immediately, she responded much better to this new doctor’s demeanor.

“(The doctor said), ‘This is not going to define you,’” Ellis remembers. That touched her because of how dedicated she was to continuing her education. “I worked so hard to get into medical school. I did not want to have to take time off because of getting diagnosed with cancer.”

Ellis underwent genetic testing and learned she had a mutation to her BRCA1 gene, which increases the risk of breast cancer recurring, as well as developing ovarian cancer, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. She was diagnosed with stage 2 breast cancer and additional imagining showed masses in her right breast. Ellis decided to get a double mastectomy with breast reconstruction.

“They did two biopsies on the right breast, and it turned out this was actually fibroadenomas,” she says. “It freaked me out so much that I was like, ‘You know what? I would just rather do the double mastectomy.’”

Triple negative breast cancer

Dr. Allison Aggon, who also attended Philadelphia College of Osteopathic Medicine, treated Ellis.

The type of cancer Ellis had, triple-negative breast cancer, can be more aggressive. It doesn't have any hormone or protein receptors attached, and there are fewer treatment options. Most patients with this cancer undergo surgery, chemotherapy and radiation, though treatment depends on how much the cancer has spread.

“Hormone-driven breast cancers are still the most common breast cancers we see in all women in general, but triple negative tends to be more common in younger women,” Aggon, associate professor of surgical oncology at Fox Chase Cancer Center, tells TODAY.com. “I don’t think we really know why exactly.”

Recent data shows some cancers are on the rise in young people. That’s why Aggon encourages younger patients who notice any changes in their breast to be proactive about seeking medical care.

“Women need to be empowered to know that any changes they appreciate should be taken seriously. And providers need to be aware of that, too," she says.

She says women who notice a lump or a change in their breast should schedule a visit with a primary care physician or an OB-GYN. Those doctors will likely recommend follow-up ultrasounds or mammograms to help understand what the change might be.

Many women with BRCA1 mutations opt for double mastectomies, much like Ellis. That reduces the chance of recurrence.

“She has minimized the chance of her developing a second, unrelated breast cancer,” Aggon says. “Since she has had the bilateral mastectomy, she no longer requires screening with mammograms or MRIs. She only needs a physical exam.”

Women should understand their risk for breast cancer, which includes knowing one’s family history of it. It’s also important to begin screening when it’s recommended.

“Breast cancer does not discriminate,” Aggon says. “Even if you don’t have a family history of breast cancer, it can affect you. It affects one in eight women, and 10% of women under the age of 40 get breast cancer. So, there’s always the possibility that you need to be an advocate for yourself.”

Medical school and breast cancer

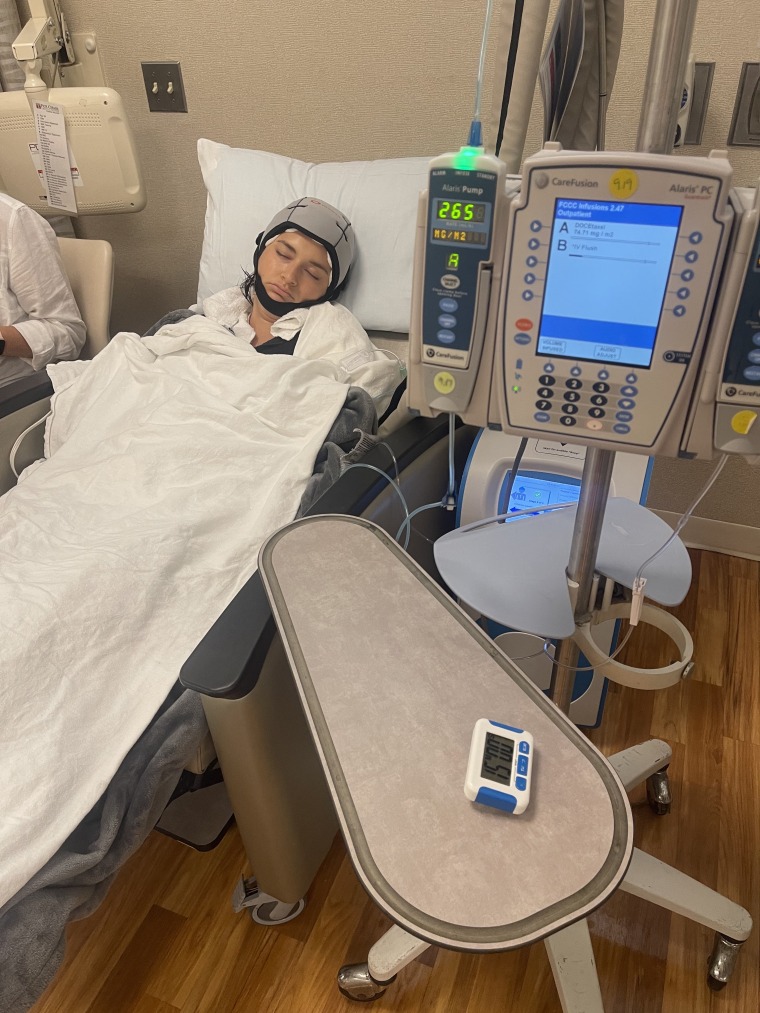

Now a third-year medical student, Ellis didn’t want cancer to slow her progress in school. She scheduled her mastectomy and treatment around her board examinations. After recovering from surgery, she took her boards and then started chemotherapy a week later.

“I told the school I want to stay on track for graduation, and originally, they were like, ‘Are you sure you don’t want to take more time off?’” she says. “(I said), if I need to take more time off, I will take that time off, but try to help me accomplish my goal of staying on track for graduation. And they did, and I’m extremely thankful.”

Already, her experience having cancer has helped her as a medical student, and she believes she’s cultivated even more empathy for patients. Just recently in her hematology-oncology rotation as part of school, she met at 22-year-old facing cancer, and Ellis shared her experience.

“I was like, ‘It may seem like your whole world is collapsing right now, but you’re going to take it one step at a time, and you’re going to get through treatment,’” she says. “That girl just hugged me and was like, ‘Oh my God, thank you so much.’”

Ellis shared her story so others realize that breast cancer can occur in younger women and to encourage others to advocate for themselves.

“It’s important that you speak up and you find somebody who will answer your questions,” she says. “You know your body best. … If I just took that first doctor’s suggestion, I could have been looking at a very different story.”

Aggon says Ellis is her “hero” for her willingness to speak up about her health and navigate a difficult diagnosis during medical school.

“As a physician, I know what it’s like to go through med school and she has managed to get diagnosed, get her treatment and continue in med school,” Aggon says. “She’s succeeding in medical school, and she’s advocating on top of it.”