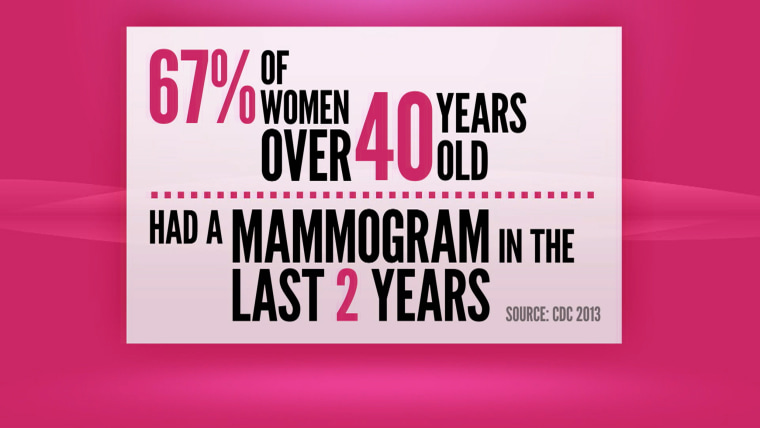

For most women age 40 or older, getting a mammogram is a yearly ritual — kind of like paying taxes.

You may not enjoy it, but you do it. Because there has long been one simple mantra: mammograms save lives.

It used to be so simple.

On October 20, the American Cancer Society said women need fewer mammograms, starting at 45. They should have them every year until age 55 and then have them every other year.

Breast cancer fighters, survivors! Join us Friday for Ambush Makeover, surprises and more!

In 2009 mammography screening recommendations took an abrupt turn when the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) released its final mammography guidelines. According to the task force, women, ages 50 to 74, were told they would reap the most benefit from biennial screening — not annual. And, among other recommendations, women in their 40s were advised to make decisions about mammography’s benefits and potential harms, along with their doctors.

Those changes caused an almost epic showdown between the task force and some physician and advocacy groups. Even politicians got involved.

Today, largely due to congressional action, most U.S. women don’t pay a dime for their yearly breast x-rays beginning at age 40.

But it’s been six years. And this past April, the task force released updated mammography draft recommendations.

The draft has a familiar ring: Women ages 40-49 should weigh the potential benefits and harms of mammography in concert with their doctors, and women ages 50-74 should get a mammogram every other year.

The task force also found “insufficient evidence” to support recommending mammograms in those 75 and older, or for the use of 3-D mammography (tomosynthesis) for screening. They also found insufficient evidence to support the screening of women with “dense” breasts with ultrasound or MRI, for example.

To be clear, these are “draft” guidelines and the task force is currently reviewing public comments before releasing its final recommendation to be published in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

Those comments could number in the “thousands,” explains Dr. Richard Wender, cancer control officer for the American Cancer Society, which is in the process of updating its own guidelines.

Woman's battle with breast cancer inspires husband to take a wild ride

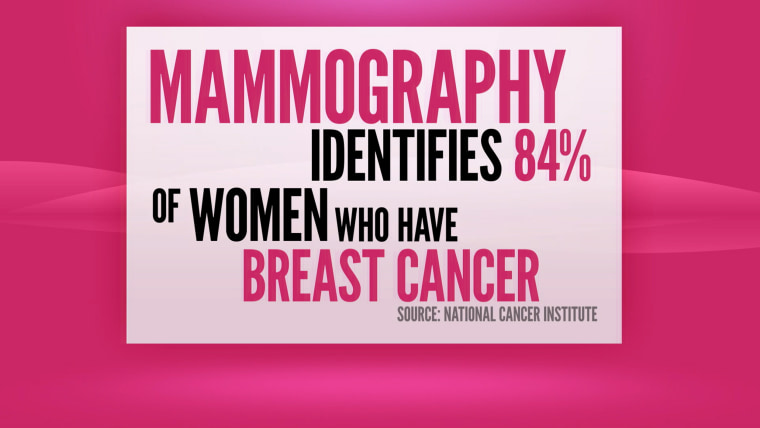

“Mammograms aren’t perfect," says Wender. "They don’t prevent every death from breast cancer. But right now getting a mammogram is still the most effective thing a woman can do to reduce her risk.”

He is quick to add: “The task force recommendations confirm that.”

A Delicate Balance

Indeed, the task force does not say that mammograms are ineffective. But there is worry among some experts that mammograms, especially for younger women (40-49), may no longer be covered completely, leading some women to skip the test.

There are also concerns that biennial screening simply isn’t enough.

And then there’s the issue of so-called over-diagnosis and stage-zero cancer, also called ductal carcinoma in situ. Largely due to mammography, DCIS now accounts for about 20 to 25 percent of all breast cancer diagnoses. Some experts believe DCIS may never cause a woman any issues, but doctors don’t have any tool to tell women whether her condition may progress. Therefore, all cases of DCIS are treated.

It’s important to understand that making any kind of screening recommendations is a delicate balance between risk and benefit. And mammography is fraught with emotion, some politics and seemingly never-ending mixed messages.

New study on breast cancer "stage O" raises more questions

“What we want women to know is what that science tell us about what screening provides in terms of benefits and of harms,” says USPSTF vice chair Dr. Kirsten Bibbins-Domingo. ”We want to do is empower women to make informed choices.”

And though the task force did receive “lots of comments” regarding the mammography screening draft, it’s important to know not all the comments were negative, says Dr. Michael LeFevre, immediate past chairman of the USPSTF, with some people saying the task force didn’t come down hard enough on mammography’s limitations.

Sifting Through the Studies

The USPSTF's new 2015 draft recommendations (which are given letter grades) are based on a mind-boggling number of studies and computer models all relating to mammography’s benefits and potential risks among women, ages 40 -74, and women, ages 50-74.

According to the task force analysis, women, ages 40-49, who are not at high-risk of the disease, should make an individual decision, since false-positive tests and unnecessary biopsies are more common in this age group. This recommendation is given a “C,” which means the task force “selectively recommends” the service and that doctors are advised to offer the test to patients based on their “professional judgment and patient preferences.”

But the task force does say: “Women with a parent, sibling, or child with breast cancer may benefit more than average-risk women from beginning screening between the ages of 40 and 49 years.”

Women who are 50-74 should get a biennial screening. That’s given a “B” rating: basically, there’s more benefit to getting screened in this age group, and getting a mammogram every other year provides just about the same benefit as annual screening.

“Most people reviewing the science of mammography have reached the same conclusion that mammography can reduce the chance of a woman dying from breast cancer, and all would say that benefits (of mammography) increase with age,” says LeFevre, professor, Family and Community Medicine at University of Missouri.

“I want to be very clear. We never said there are no benefits to women in their 40s, but the net benefits are smaller and the potential risks are greater.”

An analysis of biennial mammography screening was conducted by six independent modeling research teams from eight academic institutions, all of whom are part of CISNET, the NCI-funded Cancer Intervention and Surveillance Modeling Network and researchers from the Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium. This analysis — and others conducted by this group — help inform task force mammography recommendations.

This specific analysis found, among other things, that screening biennially from ages 50-74 achieves a median 25.8% breast cancer mortality reduction — averting 7 breast cancer deaths per 1,000 women screened and leads to 953 false positives.

Starting biennial screening at age 40 averts one more death from breast cancer and generates 576 more false positive tests and one more over-diagnosed cancer for every 1.000 women screened.

Here is a simpler way to look at it: for every 1,000 women screened every other year in their 40s through age 74, versus 50 through age 74, one additional breast cancer death will be averted, from eight to seven. But the so-called harms are high: 576 additional false positive tests, 58 unnecessary biopsies and two additional over-diagnosed tumors.

But What About Me?

All of these numbers raise the critical question: What if you were that one woman whose death was averted?

That’s tough to answer, says medical oncologist Dr. Jame Abraham, director of the Cleveland Clinic’s Breast Oncology Program. An individual woman really shouldn’t determine whether to screen or not to screen on any one study, a meta-analysis of many studies, or any computer model, which looks at the population as a whole. Rather, women need to evaluate their own individual circumstances.

“Medicine is not a linear science, it is an art,” says Abraham, who has served as the principal investigator of more than 50 clinical trials. “What I do know is that mammography is a low-cost and low-risk procedure that saves lives. I err on the side of caution.”

And although he is a scientist who appreciates the back-and-forth volleys of scientific discourse, he also treats breast cancer daily and knows the cost to women and their families.

“My wife is 44-years-old and is not at high-risk for the breast cancer,” Abraham says. “I love her and I tell her to get a yearly mammogram.”

Still Some Concerns

Groups like the American College of Radiology and Society for Breast Imaging are concerned about the draft guidelines.

Among their issues, is their belief the task force “. . . limited its consideration” to science that underestimate the benefits of regular screening, while inflating claims of over-diagnosis.

"I respect the task force and their specialties but there is not one breast cancer or breast imaging specialist on that committee and we are the best equipped to evaluate these studies,” says Dr. Debra Monticciolo, chair of the ACR's Breast Imaging Commission.

Among those studies cited by the ACR as showing mammography’s benefits is a recent Pan-Canadian Mammography Study of more than 2.7 million women. The study showed an average mortality reduction of 40 percent, which was the same for women 40-49 as for older age groups. An analysis published in the American Journal of Roentgenology shows that at current mammography screening rates, annual screening starting at age 40 saves approximately 6,500 more women's lives each year in the U.S. than the USPSTF recommendation of screening every other year starting at age 50.

And as far as anxiety about false positives? They point to two JAMA studies showing that short-term anxiety regarding results rapidly decline over time and that nearly all women who experienced a false-positive exam support screening.

The American Cancer Society has some concerns about the “C” rating for mammograms among those women ages 40-49, since “. . .coverage for screenings that receive a 'C' rating from USPSTF is not mandated under the Affordable Care Act,” according to a statement from the society’s Dr. Wedner.

The society also “. . .strongly supports coverage of breast cancer screening for women in their 40s, and will work to ensure that coverage remains available for screening when a woman and her doctor decide it is in her best interest,” he said in the statement.

Remember – Mammograms Do Have Value

The best advice is to talk to your doctor about your own personal risks and the benefits and potential harms of mammography, by age.

“As a woman, and a consumer of healthcare and guidelines as well, I do understand that it can be difficult for both patients and their doctors,” says the task force’s Bibbins-Domingo, professor of medicine and of epidemiology and biostatistics at the University of California, San Francisco.

Although different physician and advocacy groups have different guidelines regarding mammography, all of them have a woman’s good health as their top concern, she says.

And no one — not the task force, cancer experts or any guideline from any group — say that mammograms lack value.