On a moonlit night in the spring of 1862, six slaves stole one of the Confederacy's most crucial gunships from its wharf in the South Carolina port of Charleston and delivered it to the Federal Navy. This audacious and intricately coordinated escape, masterminded by a 24-year-old sailor named Robert Smalls, astonished the world and exploded the Confederate claim that Southern slaves did not crave freedom or have the ability to take decisive action.

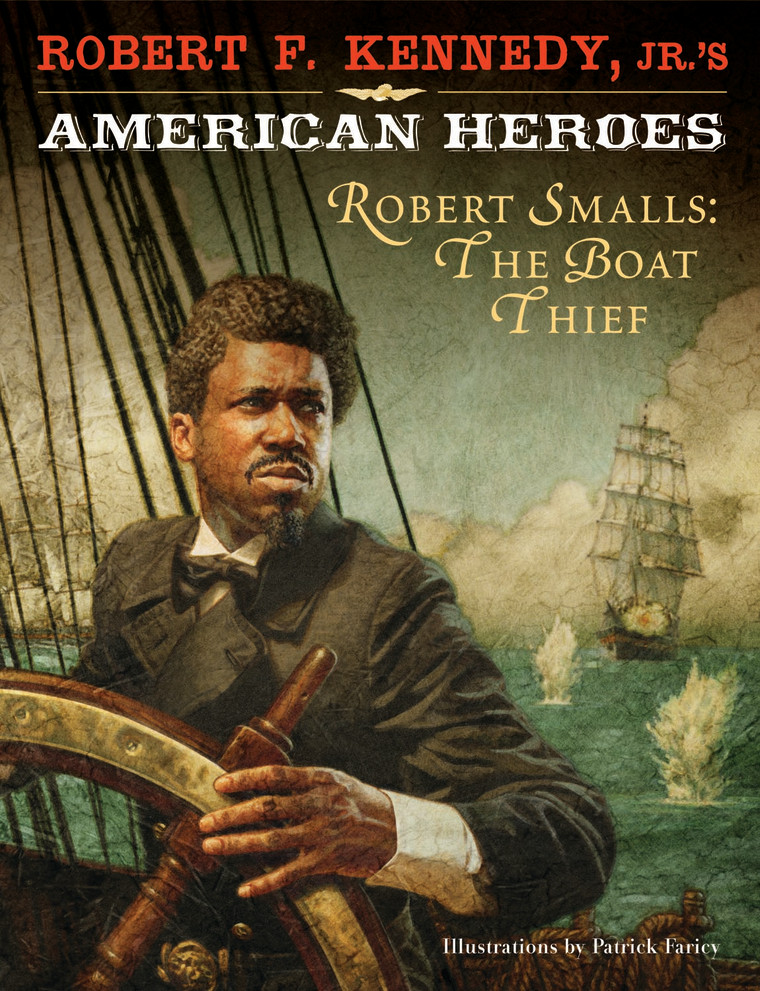

In his new children's book, Robert F. Kennedy recounts the story of Robert Smalls, who would go on to become a captain in the Navy. An excerpt.

IntroductionCharleston. One year before, the Confederate bombardment of Fort Sumter had launched the American Civil War. Confederate forces now occupied Fort Sumter and the many fortified islands that guarded the Rebel harbor. The Union forces had enjoyed very little in the way of good news since the Confederate takeover of Charleston.

Then, on a moonlit May night, nine black slaves stole the Confederate commander’s gunship as it lay tied to a wharf in front of Confederate headquarters in Charleston Harbor and delivered it to the American navy. The vessel, a giant side-wheel steamship called the Planter, was the fastest ship in the harbor. She was the pride of Charleston and the most important ship in the local Rebel fleet. The daring slaves had commandeered her from under the noses of twenty-one Confederate troops guarding her from just a few feet away.

The brassy getaway riveted world attention and enraged the Confederate government. The loss of their finest ship, with its load of irreplaceable cannons and ordinance, was a terrible blow to the Rebel cause. But, even worse, the audacious and intricately coordinated escape exploded the Confederate claim that Southern slaves did not crave freedom and were incapable of decisive and deliberate action.

The saga of courage at the birthplace of the Civil War electrified Northern states weary of disastrous reports from the battlefield. The New York Times proclaimed the noble feat “one of the most heroic acts of the war.” Northern papers praised “the plucky Africans” for their gallantry. They acclaimed the plot’s ringleader — a illiterate slave pilot named Robert Smalls—as a national hero. Smalls, they said, had proven that black slaves were ready for full freedom and citizenship. The New York Daily Tribune asked, “What white man has made a bolder dash or won a richer prize in the teeth of such perils during the war?” The paper concluded that Smalls’s actions had shown that “Negro slaves have skill and courage. They will risk their lives for liberty.”

The daring adventure shattered widespread stereotypes about African slaves and inspired the broad public support that encouraged President Abraham Lincoln to issue the Emancipation Proclamation, freeing the slaves and giving them full United States citizenship.

Both North and South were ravenous for every detail about this extraordinary slave, Robert Smalls, who had masterminded this magnificent escapade.

This is his story.

Chapter three

None of the slaves would sleep that night.Around 3 a.m., Smalls silently broke into the officers’ quarters to steal the broad-brimmed, straw Confederate captain’s hat and the captain’s uniform and pistols. The slaves all swore to one another that if they were caught, they would detonate the ship’s explosives, sink the Planter, and die fighting.

Knowing the captain and mates might return as early as 5 a.m., they fired up the steam engines at 3:30. The roar seemed loud enough to waken the whole city. Thick smoke from the stacks swept down onto Charleston. A terrifying eternity passed as the eight men waited for the steam pressure to build, frightened that the howling, billowing turbines would alert the captain or cause someone to sound the fire alarms. They prayed that the armed

Confederate guards who patrolled the wharf, expecting an early departure, would not sound the alert. When the pressure was sufficient, Smalls ordered his men to loose the lines and raise the Confederate flag. Then he blew the Planter’s whistle to signal they were leaving the wharf. Smalls stood beside the wheelhouse at the captain’s post, wearing the captain’s hat and uniform. He held his arms akimbo, imitating the captain’s well-known posture.

Shielded by darkness, the Planter steamed slowly across the harbor to the dock where the women and children were secretly stowed. As soon as they had climbed aboard, Smalls turned his ship and sailed leisurely seaward, passing six fortified Confederate checkpoints bristling with deadly guns, and sounding at each the prescribed coded signals, which Smalls knew by heart.

The tide was against them, and they did not reach Fort Sumter till daylight. As they passed the great fort, Smalls fetched up his collar and pulled the straw hat low to hide the black skin of his face. He pulled the rope, making two long whistles and a short jerk—the code for guard boats leaving the harbor.

The officer on watch signaled to him to pass, and Robert, cool as ice, steamed at a crawl directly under Fort Sumter’s steep stone walls and powerful cannons. In that moment of greatest peril, he prayed to himself, “Lord, you brought Moses and the Israelites from slavery, safely across the Red Sea. Please carry your children now to the promised land of freedom!”

As soon as she was beyond Sumter’s guns, Smalls buried the Planter’s throttle and changed course, racing for the open sea and the blockades.

Through the morning mist, Robert could see the silhouettes of ten warships from the federal blockade squadron on the horizon. He set course for the nearest federal gunboat. As the slaves made good their escape, Robert ordered his men to strike the Confederate colors and haul up a bedsheet he’d stripped off one of the bunks.

In the crow’s nest on the federal frigate Onward, the lookout spotted the Confederate gunship coming at full speed toward them out of the fog, and sounded the alarm. Thinking it meant to ram them, the Onward’s captain,

F. J. Nickerson, brought Onward about to meet the hostile attack with his broadside guns. Just as he was about to order a cannon barrage, a sailor shouted that the ship was flying a white flag, and Captain Nickerson instructed his gunners to hold their fire. He signaled the Planter to pull in astern.

Captain Nickerson saw a dashing young black man wearing a Rebel captain’s hat, dressed elegantly in a white shirt and Confederate officer’s waistcoat, leaning confidently against the Planter’s gunwale. Doffing his hat expansively, the handsome youth saluted and called to the captain, “Good morning, sir! I’ve brought you some of the old United States’ guns.”

In front of Smalls on the Planter’s deck, eight triumphant black men began cheering wildly. When Captain Nickerson boarded the Planter, the exultant crew engulfed him, pleading that he give them an American flag to raise above their prize.

The moment the Stars and Stripes were hoisted, five more black passengers emerged from the Planter’s hatches, two women and three children. Smalls’s wife, Hannah, with tears of joy flowing down her cheeks, raised her infant son, Robert, in her arms and told him to gaze at the American flag. “It means freedom, child! Oh, Robert, it means freedom!”

Captain Nickerson greeted them cordially, and after hearing Robert Smalls’s story, sent him to retell it to the blockade squadron commander, who decided to send the Planter with its crew of escaped slaves under Union commanders sixty miles up the coast to Port Royal, the headquarters of the Union army and fleet. Their families would go to Beaufort, where they would be safe for the remainder of the war.

Excerpted from "American Heroes: Robert Smalls, the Boat Thief". Copyright (c) 2008 by Robert F. Kennedy Jr. Reprinted with permission from Disney-Hyperion.