Earlier this month, NBC’s “10.5” showed the Space Needle and the Golden Gate Bridge collapsing in separate but related earthquakes. This was followed by an even larger cataclysm that significantly altered the coastline of Southern California — as well as wiping out the Hollywood sign.

In the new big-screen disaster epic, “The Day After Tomorrow,” global warming leads to a new Ice Age as well as massive tornadoes, blizzards and tidal waves that flood Manhattan. And the Hollywood sign is once more toast.

Just as the international political atmosphere turns increasingly apocalyptic, and best-seller lists are topped by “Left Behind” and visions of Armageddon, movies are becoming more pessimistic about the fate of the Earth.

But perhaps not all is lost. There have, after all, been several Golden Ages of disaster epics, beginning in the late 1930s. While the rest of the world was preparing for war, Hollywood was filling screens with images of a city-destroying earthquake (“San Francisco”), a massive fire (“In Old Chicago”), a horrific flood (“The Rains Came”) and a South Seas disaster (“The Hurricane”).

The genre became so popular that a special category was created in 1939 to honor filmmakers who could transform disaster into entertainment. “The Rains Came,” with its still-convincing images of a dam breaking during an Indian monsoon, won the first Oscar for special effects, defeating such fellow nominees as “Gone With the Wind” and “The Wizard of Oz.”

Silent movies rarely ventured into this territory, aside from such biblical epics as 1929’s part-talkie “Noah’s Ark,” in which several extras were reportedly drowned, and the 1923 version of “The Ten Commandments,” in which the parting of the Red Sea was a triumph for some (pharaoh’s escaping slaves) but a disaster for others (pharaoh’s waterlogged army).

The 1940s were also curiously bereft of apocalyptic entertainments, perhaps because of competition from such epic real-life misfortunes as Pearl Harbor and Hiroshima. But a post-war appetite for the genre was reflected by the popularity of “Green Dolphin Street,” a cheesy Lana Turner melodrama that won the 1947 special-effects Oscar for its compelling depiction of a New Zealand earthquake.

The heyday of disaster flicks

The 1950s, of course, seemed made for the genre. “The Day the World Ended” (1956), about the survivors of a nuclear attack, promised more than its title would deliver, but “When Worlds Collide” (the 1951 Oscar winner for best special effects) did illustrate the destruction of the Earth — and the establishment of a tiny human colony on another planet.

The decade also delivered the model for the “Airport” movies, “The High and the Mighty” (1954), such seminal nuclear-holocaust dramas as “Five” (1951) and “The World, the Flesh and the Devil” (1959), as well as two treatments of the sinking of the Titanic: “Titanic” (1953) and “A Night to Remember” (1958).

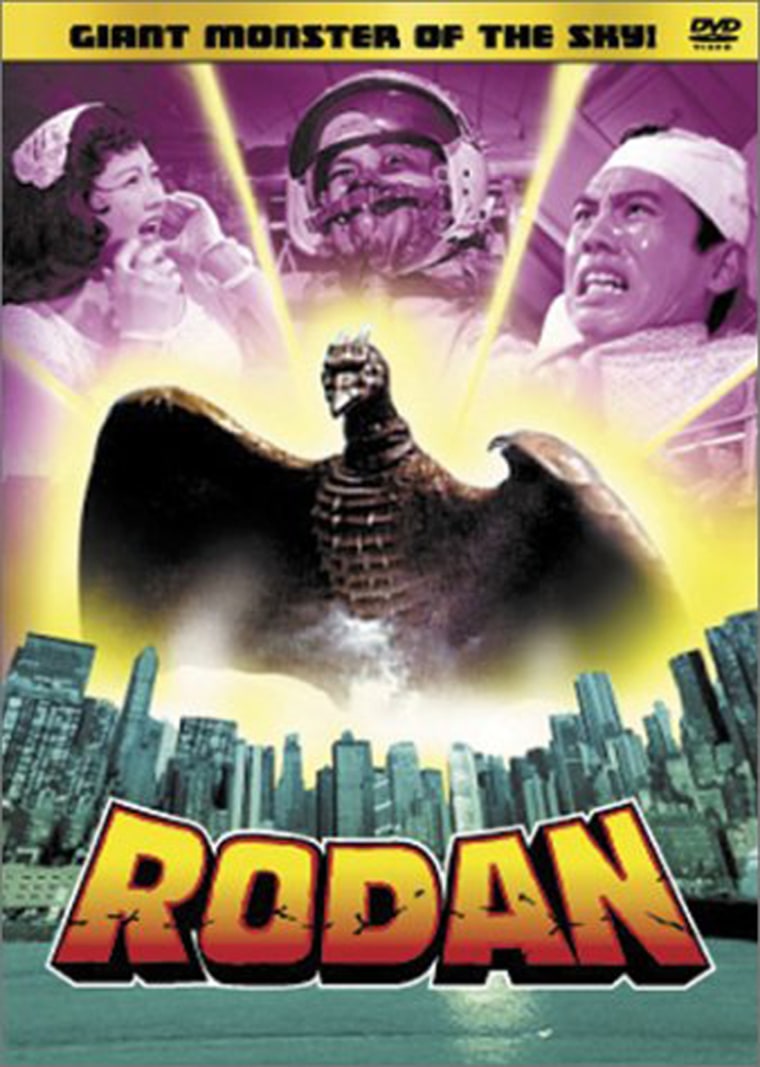

Godzilla was born in Japan in 1954, “Rodan” followed in 1956, and numerous radiated monsters turned up in the United States to climb buildings and demolish cities. The aliens in “Earth vs. the Flying Saucers” (1956) and “War of the Worlds” (1953) vaporized those who tried to tame them, while the extraterrestrials in “This Island Earth” (1955) kidnapped American scientists for a trip to their own disintegrating planet.

In her 1965 appreciation of 1950s science-fiction movies, “The Imagination of Disaster,” Susan Sontag wrote that the genre “is concerned with the aesthetics of destruction, with the peculiar beauties to be found in wreaking havoc, making a mess.”

The biblical epics of the 1950s also delivered on this score. Cecil B. DeMille brought down a temple and dozens of Philistines for the finale of “Samson and Delilah,” and he parted the Red Sea again for the 1956 remake of “The Ten Commandments.” Rome was torched in “Quo Vadis” (1951), while Nero (Peter Ustinov) found his own peculiar kind of beauty in the spectacle, reciting inane songs above the flames.

The late 1950s and early 1960s produced a more serious kind of disaster epic, exemplified by “The Day the Earth Caught Fire” (1962), in which nuclear tests send the Earth careening into the sun, and “On the Beach” (1959), in which such screen immortals as Ava Gardner, Fred Astaire, Anthony Perkins and Gregory Peck waited for deadly radiation to reach them in Australia.

A tune to whistle before the big one hitsAlthough music was important in most of these movies (the theme from “The High and the Mighty” was whistled by its star, John Wayne, and the familiar Aussie song “Waltzing Matilda” became the theme of “On the Beach”), it took the 1970s to introduce Oscar-winning songs to die for.

“(There’s Got to Be a) Morning After” accompanied the unfortunate voyagers whose New Year’s Eve Party was turned upside down by a tidal wave in “The Poseidon Adventure” (1972). If that was music to drown by, “We May Never Love Like This Again,” from “The Towering Inferno” (1974), literally provided a torch song.

James Cameron’s “Titanic” was a 1997 throwback to this sub-genre, winning one of its 11 Academy Awards for Celine Dion’s rendition of “My Heart Will Go On,” which later turned up on a frightening number of real cruises. The following year, “Armageddon” was nominated for its theme song, “I Don’t Want to Miss a Thing,” but this forgotten musical accompaniment to colliding heavenly bodies missed the Oscar.

Sontag felt that 1950s science-fiction films suggested “a mass trauma” that “exists over the use of nuclear weapons and the possibility of future nuclear wars.” That may have faded to some extent, perhaps because Hiroshima and the Cuban missile crisis now seem so far away, so 20th Century. Some thanks may also be owed to the late Stanley Kubrick, who made such a devastating joke of nuclear fears in 1964’s “Dr. Strangelove, Or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb.”

Today’s disaster epics suggest a world that’s out of control in other ways. The arrogance of technology is the not-so-hidden theme of “Titanic,” while “Armageddon” and “Deep Impact” (1998), whose heroes are so limited, hint that cosmic disaster may simply be unavoidable. “10.5” and “The Day After Tomorrow” suggest more of the same.