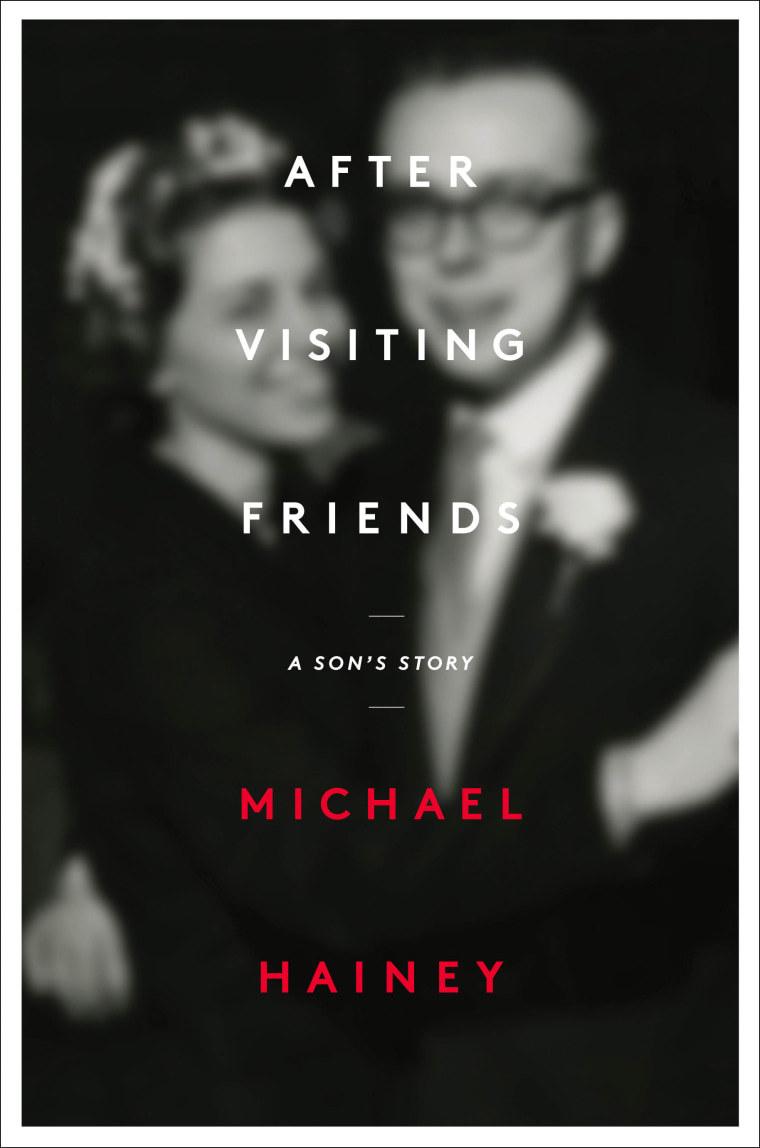

After noticing inconsistencies in the stories of his father's untimely death, Michael Hainey went out in search for the truth about the circumstances. In 'After Visiting Friends,' Hainey recounts his quest in a memoir that is both moving and mysterious. Here's an excerpt.

The night slot

My father was the night slot man. That’s a newspaper term. From the time he is a young boy of six or seven in Dust Bowl Nebraska, back in the Depression, all he wants is to work in newspapers. All he wants is to escape, to get to Chicago and be a newspaperman, just like his brother.

My dad’s name is Bob. He idolizes his brother, who is twelve years older. His brother’s name is Dick.

Their father was many things, but mostly he was a switchman and, when called upon, a griever. Those are railroad terms. Their father passes most of his life in the windblown rail yard of McCook, a town barely bigger than an afterthought. Day after day, he couples and uncouples strings of boxcars and then waits for the engines that will come to pull them apart or carry them away.

At eight, my father gets a job as a paperboy, delivering the Omaha World-Herald. In high school, he edits The Bison, the school paper. Come graduation in 1952, the Omaha World-Herald declares him “one of Nebraska’s brightest newsboys”—who has worked his route “with diligence and dedication.” They give him a “Carrier’s Scholarship”—$150. He also earns a $450 scholarship from Northwestern University and uses it to attend the Medill School of Journalism, just like Dick, who is by now an editor at the Tribune. Dick delivers the address at my father’s commencement. The Omaha World-Herald runs a story headlined TWO BROTHERS GET ATTENTION AT MCCOOK HIGH GRADUATION. The editors print head shots of Dick and my father. Beneath them, a caption: Richard, Robert . . . Speaker, Listener.

Five years later, in May 1957, my father graduates with a master’s degree in journalism. A few days after commencement, he packs up his room in a boardinghouse run by an Armenian woman on Foster Street. A Sigma Nu fraternity brother drives him and his suitcases down to Chicago’s Union Station, where he boards the Burlington Zephyr, bound to McCook.

He doesn’t want to go back to Nebraska, but Dick, who is the chief of the local copy desk at the Chicago Tribune, tells him that it is all but impossible to get hired at the Tribune straight out of college. “Most of the reporters didn’t even graduate from high school. You need experience. That’s the only way they’ll respect you.

”The McCook Daily Gazette is in search of a managing editor for a special project, and my father takes the job. The town is getting ready to celebrate the seventy-fifth anniversary of its founding. In 1882, the Burlington & Missouri River Railroad needs a way station between Denver and Omaha where it can switch out crews and add a more powerful locomotive for the climb through the Rockies. They name the nothingness after General Alexander McDowell McCook, a Union soldier in the Civil War who spends his prewar years wandering the frontier, putting down Indian uprisings.

The Gazette is a small paper, but my father consoles himself with the fact that it’s a daily and it covers all of southwest Nebraska. Just as the Great Depression hits, the Gazette buys a propeller plane, christens it the Newsboy, and claims to make journalism history by becoming “the first paper in the world to be regularly delivered by airplane.” Every day, the Newsboy takes flight from an airstrip notched into a cornfield on the outskirts of town and zigzags through the skies of southwestern Nebraska and northwestern Kansas. Through a hole in the plane’s thin floorboard, the pilot of the Newsboy drops bundles of papers down onto towns even smaller than McCook. It’s all very successful until a windstorm sweeps into town and hurls the plane end over end, splintering it. So dies the Newsboy.

The paper is published in a limestone building on Norris Avenue where, above the front door, someone has chiseled: SERVICE IS THE RENT WE PAY FOR THE SPACE WE OCCUPY IN THIS WORLD. My father dedicates himself to his work, creating the Gazette’s seventy-fifth-anniversary issue. He spends that summer interviewing old-timers and digging through records at City Hall and the town library. He edits stories for the paper, as well as reports and writes.

One night, so the story goes, he and a high school buddy, Bob Morris, drive out of town and spend the night drinking beer. On the way back, they come across a road-construction site. My father climbs onto the earthmover and drives it toward the darkened river.

“What are you doing?” his buddy yells, laughing on the bank.

“Getting some experience,” my father says.

The following morning the Red Willow County sheriff calls the Gazette—he asks for a reporter to drive out to the river. My father arrives at the scene of the crime. Once there, he interviews the officers as well as the construction foreman and then publishes a story in the next day’s paper: MYSTERY VANDAL HITS CONSTRUCTION SITE. The sheriff thanks him for helping to draw attention to the crime.

He publishes the Gazette’s commemorative edition, says his good-byes, walks to the redbrick train station at the bottom of Norris Avenue, and buys a ticket for Chicago. His brother has gotten him a job as a copy editor on the Neighborhood News desk at the Chicago Tribune.

Excerpted from AFTER VISITING FRIENDS: A Son’s Story. Copyright © 2013 by Michael Hainey. Excerpted with permission by Scribner, a Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.