This story discusses suicide. If you or someone you know is at risk of suicide please call the U.S. National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255, text HOME to 741741 or go to SpeakingOfSuicide.com/resources for additional resources.

The last time I talked to my son Greg it was about the musical "Hairspray" and the message of inclusion.

I had just gone to see it with a fellow nurse, and he had seen it, too, and he talked about not feeling included. We were talking about real emotion, not just something surface-level. So, I tried to go there with the conversation and bring up mental health, and Greg cut me off.

I immediately pivoted to talking about Greg's dog, Cutty, because that was where we could always bond.

He told me he was cleaning his apartment and had taken Cutty over to the sitter. I knew in my head, “No, this is not good. He would not part with Cutty for no reason.”

So I told him, “Oh, you are cleaning, I’m coming up!”

And he said, “No, Mom — next week, next week.” So I asked what food I could bring him and he told me I didn’t have to bring anything, but I told him, “You know I’m going to bring you stuff so just tell me what you want.” He told me anything I brought would be fine.

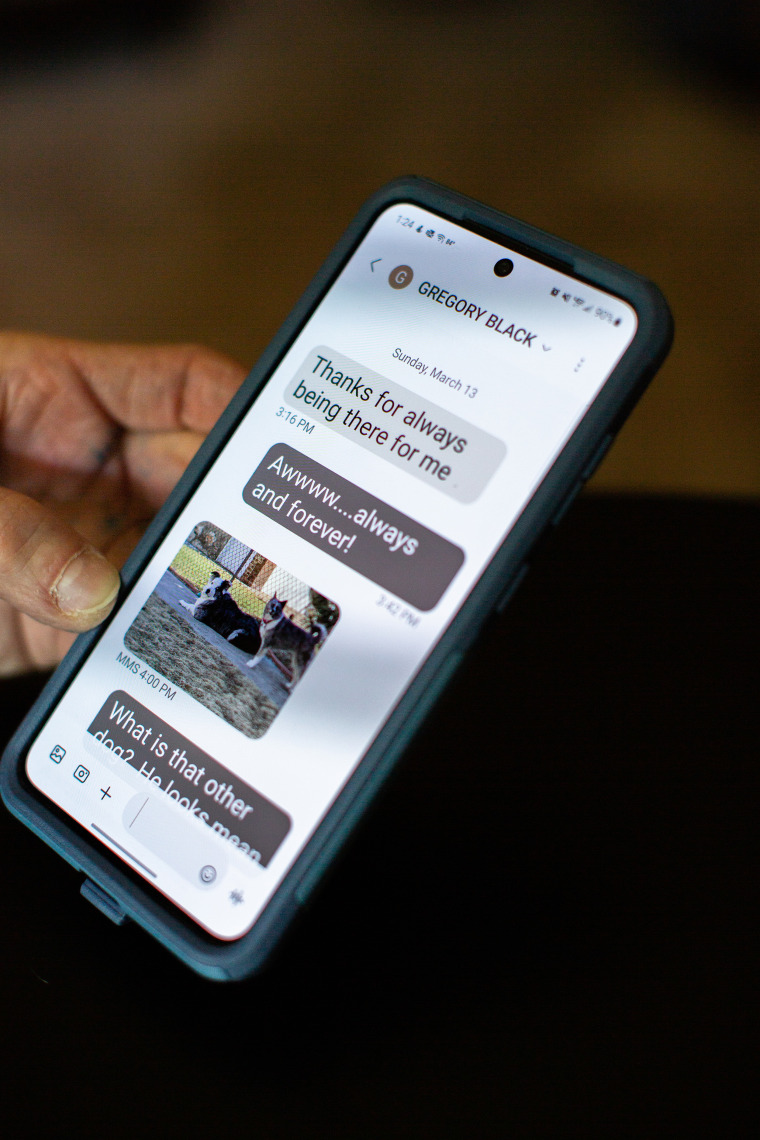

We got off the phone, and I thought to myself, “That was way too clear and concise of a conversation.” Two minutes later, I got a text from him: "Thanks for always being there for me."

I texted back, “Always and forever.” Then he sent a picture of Cutty that the sitter had sent. I was with his grandpa, and I told him his grandpa said hi, and he sent a little wave emoji back. That was at 4:30 p.m. or so, and that was the end. He died at 10 o’clock that night.

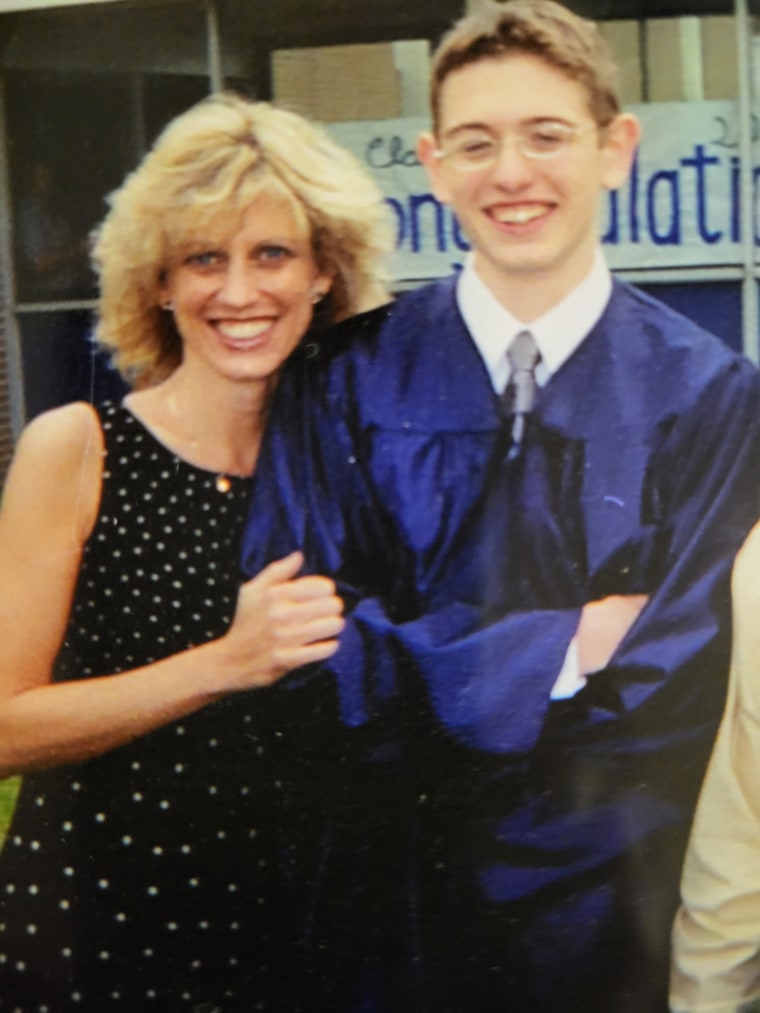

My son, U.S. Army Major Greg Black, was in front of a Veterans Affairs hospital when he took his life in his car on March 13, 2022. He was 36 years old.

At first I thought, “Oh, my baby was trying to go into the hospital, but he just couldn’t bring himself to go.” But now I realize that he was making a statement, and as the weeks have gone by, it's become more and more evident how well planned this was.

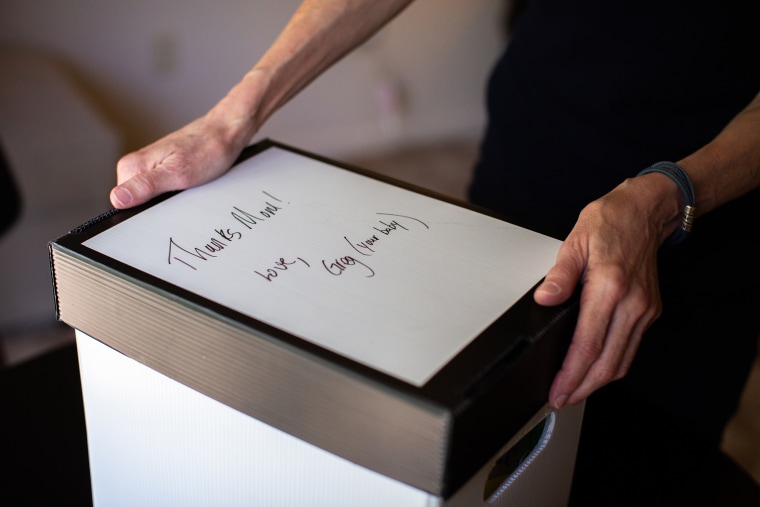

As I’ve learned more, I look back on the details with more clarity. It was all strategically planned out — he even mailed his childhood friend a baseball card that the two of them had been fighting over their whole lives.

The part that I struggle with the most is something Cutty’s sitter told me later. As Greg was walking away after dropping Cutty off, he turned around and said, “Oh I forgot to tell you, my mom’s picking up Cutty.”

He said, “Greg, where are you going?”

And Greg replied, “I’m going on vacation with my parents.”

He hadn’t seen his dad since he was 11 years old. It was a knife in my heart, because it just showed that all he wanted was his family.

Greg was miserable. He tried to do all the right things and the system failed him multiple times, until he gave up hope.

While serving in the Army, he suffered a traumatic brain injury, which led to him being medically discharged with full disability. He struggled with finding purpose outside the military. On top of that, he had a lot of problems with his mental focus, which led to headaches, severe depression and chronic pain.

Chronic pain is a beast. Imagine waking up every single day and your head hurts. Every single day. It just drains you. It's hard to be effective.

Every single minute of every single day I think about the "I should have ... " or "I could have ... " scenarios.

I think to myself, “Could he have had bipolar? Did I miss that he had depression?” I think about the first time I picked him up at the VA hospital, knowing that there were night terrors, knowing that there was profound post-traumatic stress disorder.

I replay it all. Before he died, I had started seeing a therapist who told me, “At the end of the day, Greg has got to manage it. He’s a 36-year-old major from the Army. He doesn’t want his mommy looking after him. He is trying to adjust to a new normal.”

It was a fine line, because at some point I had to trust Greg. I had to trust that as long as I had a presence, I was doing what I could.

I would drive to Greg's on Saturday mornings, take his dog out for a walk, leave them some food, but then I would get the feeling like, OK, you need to go now. So I did the best that I could, as much as he would let me do. I also knew that if I pushed too far, he would push right back.

I could tell he didn't feel good. I could see the headaches. I could see he was wearing sunglasses in his apartment because his head hurt. You could see in pictures his looks had changed dramatically. You could see the suffering and see how dark his eyes were and you could tell he wasn't getting any sleep at all.

Greg struggled to get care from a broken medical system. Prescriptions didn't arrive on time; lab results were difficult to track down. He had been waiting for more than a year to get approved for psychotherapy.

For somebody having severe PTSD with psychosis, he needed to talk to someone. He wasn't going to talk to his mother. He wasn't going to talk to his friends, because in Greg's eyes, his friends were very successful. He didn't see the struggles of his soldier friends. He saw it as, "Everyone is so successful and moving on with their life (after the military). Why is my brain broken? Why did it happen to me? Why am I being punished?"

Before Greg died, he was thriving at work and the company he was working for was getting ready to promote him. I think he used every bit of energy that he had at work, and there was nothing left afterward.

He was also going to school to be a psychiatric nurse, because he wanted to do something meaningful, and becoming a psych nurse for him meant that he could treat others differently than he was treated.

Becoming a nurse motivated Greg, and he was purpose-driven, but it was going to take him an additional year at school, due to his mental and physical struggles. I tried to tell him, "Your brain will get there. You just have to go a little slower. Maybe just go to school, or maybe just work, but trying to do both might be too much."

But in Greg's mind, if he just pushed through it — and that is such a military mindset — he should be able to do everything at once.

People who take their own lives often don't see the support systems around them, and they don't want to reach out for help, and they become more and more isolated.

As a nurse, and now as a mother who has lost her son, we have to stop relying on the answers we get when we ask questions like, "Do you feel like harming yourself?" or "Do you have thoughts about suicide?" Because people lie. Greg would say, "I'm fine," or he'd crack a joke.

I’ve tried not to say, “Greg passed away,” because people are going to figure it out. They’re going to know.

It’s very hard for me to say the word suicide, but we have to say suicide. I’ve tried not to say, “Greg passed away,” because people are going to figure it out. They’re going to know.

Greg was so distraught that he didn't even care that his legacy was going to be that he took his life. That he died by suicide. But if Greg is now that man — the one whose legacy is suicide — then I have to be the one to share his story and try to make the change he would have wanted.

Now, when someone asks me how my son died, I don't hesitate or try to be polite. I tell them the truth.

This interview has been edited and condensed.