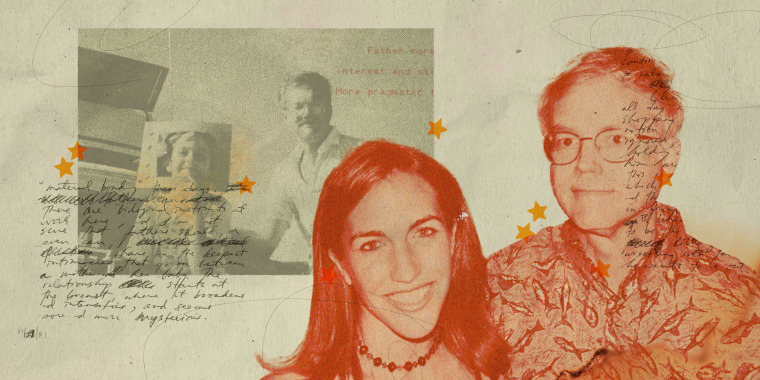

We lost my dad 20 years ago. That means I’ve now spent half my life with him, half without, though he’ll always be part of what makes me whole.

Losing a parent at a young age opens a chasm of lost time and experience. For a long time, it felt unbridgeable to me. But I’ve begun to see that the evolution of our relationship did not end when his life did.

Nothing revealed that process more than becoming a parent myself — paired with the priceless discovery of some of my father’s writings as a young man.

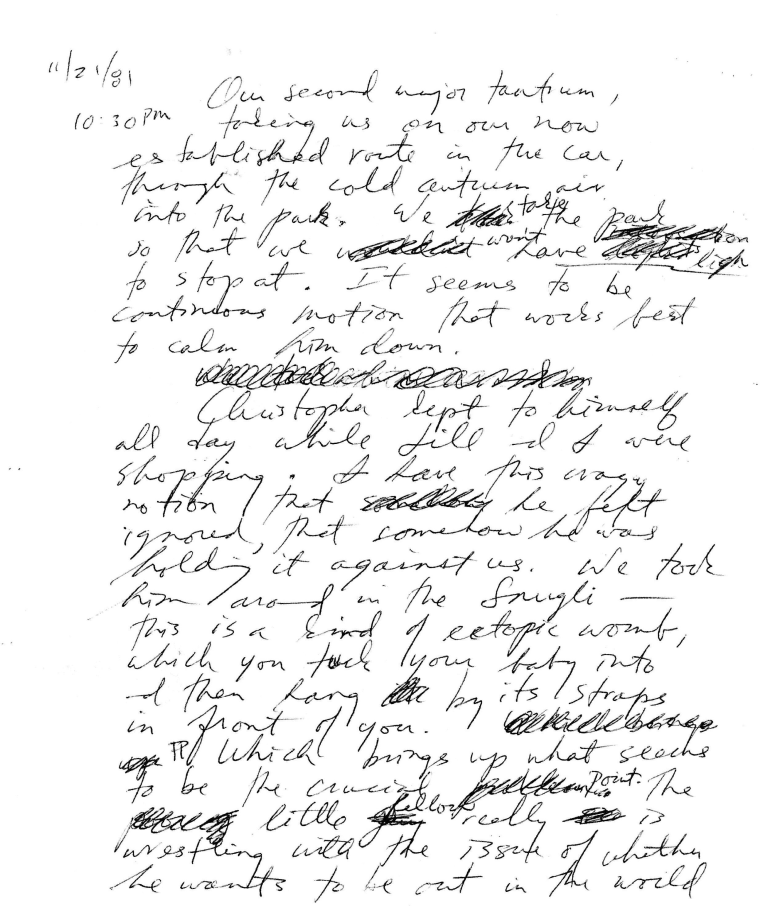

In a journal entry from my older brother’s first weeks of life, my dad remarks on the remaking of his world around “someone who did not even exist on the planet five weeks ago.” With a feeling like vertigo, I’ve stood by my own babies’ cribs imagining my father looking down at me with that same intensity of love.

Knowing the raw, vulnerable, at times maddening devotion of parenthood gives me a vastly different appreciation for my dad’s motivations.

In another entry he talks about how tired he is, how the furnace is acting up and he’s bracing for a tough Monday at work. Alongside mundane details are deeper reflections. He empathizes with my brother’s “every discomfort” feeling like “utter disaster … compared to that timeless, all-supporting sea inside a pregnant woman’s body.” He notes, “Things are often not as bad (or as good) as we feel at the time.”

Picturing my dad as an exhausted young father, trying to crack the code of this new baby’s demands, lends new texture to help me fight the ways that memory can flatten over time.

Connecting to his thoughts at a similar stage in our lives feels like reopening a conversation after years stuck in a one-sided loop, wondering what else I could have said during the year when cancer stole his strength. Having my own children helps me see the child I still was at 20, and offers deep reassurance of how much my father understood.

My dad used to say he could write the script for how people would react in any situation. I now find myself rewriting memories with new insight into his perspective. Becoming a parent myself has given me a bird’s-eye view of my father’s experience that has softened old blows and freed up space to celebrate how profoundly interesting, how truly remarkable he was.

I’ve also marveled at how life continues through a new generation. A thought, it turns out, my father had from a startlingly young age.

My dad, an avid science fiction fan, wrote a piece for his high school literary magazine titled: “Because of their Children.” It’s a conversation between alien or celestial beings that begins with the words: “They die, you know.” The immortal beings discuss the pitfalls of living forever, the fear of letting go, and the human alternative.

One says, “We can’t die and still live.” The other answers, “But we can. We can have children… It’s another kind of immortality, child-bearing, the kind they stumbled on here. Everything we know we would teach our children. We would tell them all that we have seen or thought we’ve seen, and they would know us and be us. And when we’d die they would make us greater than we could ever be, because they would add their knowledge to ours.”

They’re oddly prescient musings for a teenager and they reflect the ceaselessly curious man who couldn’t, and in the end didn’t, get enough of life.

As a young man, Jack Barr went to see Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. preach at his church in Atlanta. As a doctor for 30 years, he treated the bodies and minds of thousands of patients, and every one he treated with respect. As a father, he taught my brother and me to stand on principle, to work hard and with purpose, to seek out new ideas, and to have fun.

Every night when he tucked me in, he would ask if I had any questions. I have so many now. But I do know this: You can die and still live. Dad, I carry your voice with me every day. Your grandson bears your name. We call you Grandpa Stars and we know that you’re always our guide.