When nurse MarlaJan “MJ” Wexler-Gormley was caring for a pediatric patient before his heart transplant, he noticed something that sparked a touching moment.

“Scrub tops are V-necks. It’s not like I had (my scar) out on display,” Wexler-Gormley, 40, of Philadelphia told TODAY. “But, the patient grabbed my hands and said, ‘Oh my gosh, you’ve had open heart surgery. That’s a zipper!’”

People who have had open heart surgery often refer to the scar on their chest as a “zipper.” Wexler-Gormley — now a nurse at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) — had undergone open heart surgery three times as a child, which are details she often keeps to herself. She didn’t want to burden patients with her story. But this child wanted to know more.

“I really tried to defer away and talk about him. He was about to go in for a heart transplant,” she recalled. “He was like, ‘You have to tell me. It’s going to make me less anxious.’ … I told him my own story and I just remember the look on his face. The anxiety and fears he was feeling came down a little bit. We bonded in a way that I had never bonded with a patient.”

CHOP has always been a part of Wexler-Gormley’s life. She had her first surgery there at 6 months old for a congenital heart defect (CHD) and has worked there. Her story reflects how far treatment of congenital heart defects has come.

“My generation is really the first generation of CHD patients who have not only survived but also thrived into adulthood,” she said. “As devastating as CHD can be parents can look to people like me who have been through this again and again and we have not only survived but also have really shown the world that we can do it and we’re going to make our own mark.”

‘Something wasn’t right’

After Wexler-Gormley was born in August 1981, doctors noticed she had a heart murmur. An echocardiogram revealed a “very small ventricular septal defect.” While that sounded worrisome, doctors explained to her parents that it would resolve on its own.

“They were reassured several times that I’d never need any type of surgical intervention … and I would go on to be a bright healthy baby girl,” Wexler-Gormley said. “When my parents brought me home, quite quickly things changed.”

She struggled to eat and after only a few minutes of feeding, she fell asleep. Her parents noticed she often grunted and was sweaty and short of breath. She started losing weight.

“My mom had this feeling that something wasn’t right,” she said. “My mom got tired of being told that nothing was wrong. They call it mother’s intuition for a reason.”

Her mother visited CHOP for a second opinion.

“My parents’ lives were totally flipped upside down and I was diagnosed with a congenital heart defect, tetralogy of Fallot,” Wexler-Gormley said. “I was already in congestive heart failure and started medications immediately.”

Tetralogy of Fallot is congenital heart defect where structural abnormalities impact the blood flow in the heart, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. It can mean there is less oxygen in the blood that moves to the rest of the body, causing some babies to look blue. Babies with it often experience arrhythmia, dizziness, delayed development and contract infections in the heart.

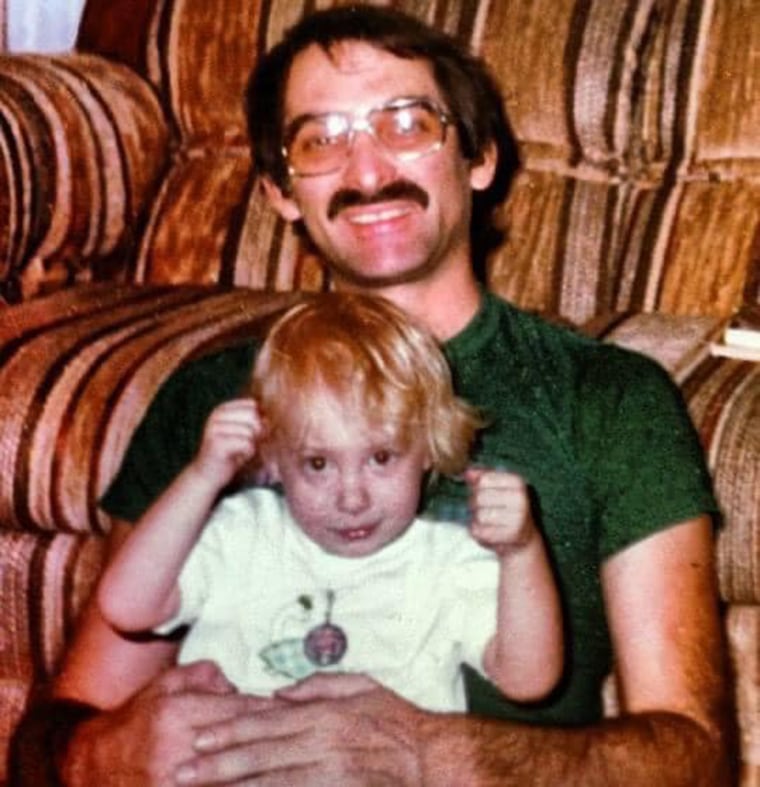

When she was 6 months old she underwent a procedure to help her until she was big enough for a surgical repair. At 2, she had her first open heart procedure, grueling for her parents because she went into cardiac arrest a few hours into it. When she was 4 and 6, she had two more open heart surgeries. As she aged, she started understanding what all this surgery meant.

“I was aware of my own mortality,” she said. “Some experiences were scary. They were painful. Even at that age I was able to realize that my body didn’t feel like my own body.”

Prior to her last surgery, she was completely dependent on oxygen and the medicines to treat her heart failure were no longer helping. While surgery at 6 helped her tremendously, she knew one day she’d need to undergo yet another procedure to have her pulmonary valve replaced.

Meanwhile, she returned to a more normal life with some restrictions. She couldn’t always participate in gym or sports and she had scars that her peers didn’t. In school, she excelled in science and thought in high school she might become a forensic pathologist.

“That was the time that ‘Law and Order’ really started to become big and I thought I was going to be the next Olivia Benson,” she said. “I watched my first autopsy and fell flat on my face.”

She graduated from college with a biology degree and wondered where to go with her career. Then she had a conversation with a friend’s mom that changed her future.

“I had talked to her about my experiences and what I had gone through as a child,” Wexler-Gormley recalled. “She told me about nursing and it dawned on me.”

She recalled pictures of her as a child at the nursing station with her favorite nurses and remembered the impact they had on her. She applied to nursing schools.

“I only wanted to work in pediatric nursing,” she said. “One of my professors had her career in inpatient nursing at CHOP and she really paved the way for me to realize that is where I wanted to be.”

Coming full circle

Through a clinical trial, Wexler-Gormley received a new pulmonary valve in 2020. It had been 34 years since her last open heart surgery. Helping children and their families has been transformative.

“Being able to give back to CHOP and working with CHOP families, it’s just been so incredible,” she said. “It really helped me, psychologically, going through some fears and anxieties that I still deal with.”

She hopes that her experience as a child who survived CHD and thrived into adult inspires optimism in parents learning that their infants have CHD.

“There is hope that your child can survive and not only survive but also do amazing things,” she said. “It’s extremely helpful and beneficial for families to see these stories and that life is going so much further beyond this diagnosis.”

Her experience with the young boy awaiting a heart transplant changed her perspective and she recently reconnected with his mother.

“It was just a beautiful moment for myself, for him and his parents — just for them to know that someone who is giving him care has been in that bed before, had been through all of the frightening procedures and surgeries,” she said. “That moment really struck a chord.”