A New Hampshire toddler who suffered a nightmarish injury when a pencil impaled her eye and became lodged in her head was saved by a remarkable turn of good fortune: The pencil that penetrated deep into her brain took a near-perfect path that left her virtually unscathed.

The girl, 20-month-old Olivia Smith, survived not only the pencil’s pushing through her brain, but also its painstaking and dangerous, yet flawless removal at Boston Children’s Hospital, where the pencil was slowly pulled out by hand earlier this month.

“It’s beyond belief how lucky she was,” said one of her doctors, Dr. Darren Orbach. “Her prognosis is great. I would expect her to be a normal kid at this point.”

Olivia’s improbable tale began on Jan. 6, when she was coloring at home in New Boston, N.H., lost her balance and fell onto the pencil, said Orbach, chief of interventional and neurointerventional radiology at Children’s.

When her mother picked her up to comfort her, she saw a small piece of the orange colored pencil sticking out from her right eye.

“I thought the pencil had broken or something,” Olivia’s mother, Susie Smith, told NBC affiliate WHDH. “I thought there was no way that whole pencil was through her head.”

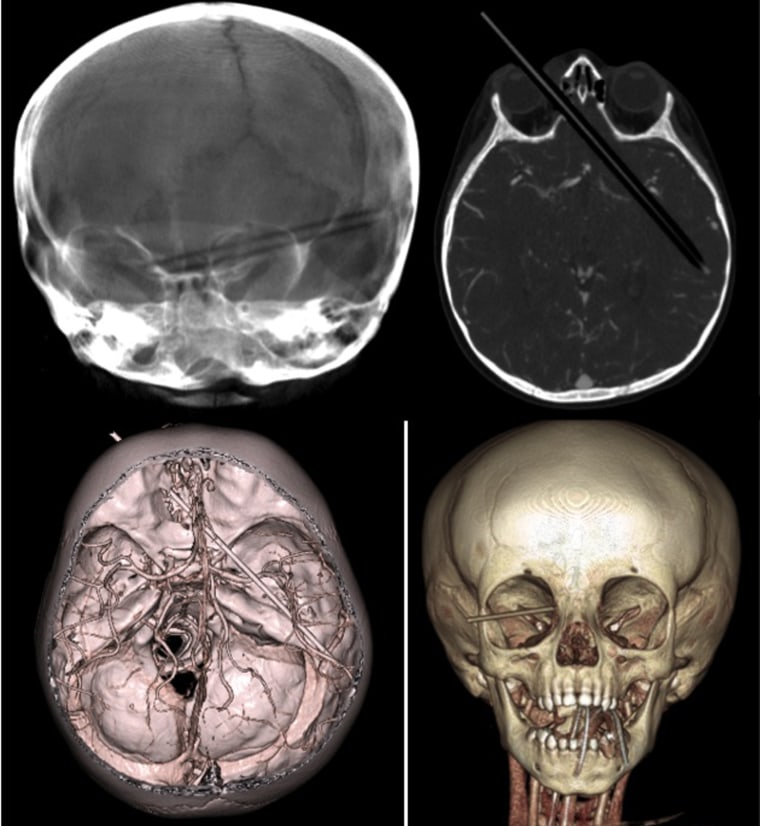

But most of it was. Olivia was rushed to a New Hampshire hospital and then airlifted to the renowned Boston Children’s Hospital, where scans showed that 4 to 5 inches of pencil were stuck in her head.

The pencil entered the eye socket, passed through the bottom of the brain’s right hemisphere, crossed the midline and went through most of the left hemisphere, stopping just short of her left ear, Orbach said.

Along its route, it managed to avoid important areas like the optic nerve, critical arteries and veins and other parts, that, if damaged, could have caused blindness, paralysis, devastating neurological damage, or death, Orbach said.

“It missed everything,” he said. “Almost any horrible outcome that you could imagine could have happened.”

While penetrating brain injuries usually cause bleeding that can be life threatening, a CT angiography scan done before the removal showed that in Olivia’s case, there was none, Orbach said.

“The CTA was probably the most remarkable scan I’ve ever seen,” he said. “If you follow the course of the pencil across the brain, the entire brain, it literally missed every major vessel in its path by millimeters.”

The pencil was removed in a delicate duet in the hospital’s angiography suite, where Orbach worked with pediatric neurosurgeon Dr. Shenandoah Robinson.

Robinson pulled the tightly lodged pencil ever so slightly and then Orbach checked each newly liberated area for bleeding by performing cerebral angiography, which provides live, computerized images of the arteries after dye is injected through a catheter.

“We had her pulling very, very slowly,” Orbach said. “Just a few millimeters, then she would pull half an inch to an inch each time.”

Though doctors were confident the plan would work, the procedure was dangerous; fatal bleeding could have occurred at any time, Orbach said.

Orbach had a microcatheter on hand to deploy surgical glue or tiny coils to quickly stop any bleeding during the extraction. But it was never needed. “There was no bleeding at all internally during the removal,” he said.

The procedure took about three hours, with about 45 minutes of pulling and monitoring. “As it was coming out, we kept on groaning about how long it seemed,” Orbach said of the pencil.

Olivia was kept sedated for a day and was slow to wake up, with weakness on her right side, Orbach said. An MRI showed that she suffered a mild stroke from the initial injury. But she made a rapid recovery and returned almost to normal within days, he said.

Orbach recalled seeing Olivia sitting up, laughing and eating ice cream, not showing any signs of what she had been through.

“You could not see a thing, just looking at her,” Orbach said. “That was just an emotional moment for me. It was such a stark opposition to the way I met her.”

Olivia may retain a very slight weakness on that one side of her body.

“Maybe she won’t be a gymnast, but in every other way, she will be completely normal,” Orbach said. “She’s not going to have any significant disability. At worst, she’ll have very mild weakness on the right side.”

The pencil’s pathway was so unlikely that Orbach said he could not have easily imagined coming up with such a benign route.

“If you asked me to take a scan and draw a trajectory from one side to the other side, missing every vessel on the way, and all the critical structures of the brain, I would have a really hard time doing it,” he said. “This pencil did, remarkably, that.”

Olivia spent less than a week in the hospital followed by a brief stay at a rehabilitation center. She is now back home, running, drawing and playing with her dolls.

“It was amazing to look at it,” Smith told WHDH, “But it wasn’t amazing to go through.”

Related:

Baby born with heart outside her chest going home