In January, Sammy Berko, 16, scaled the wall at a rock climbing gym, rang the bell at the top and collapsed. Staff brought him down and a bystander began performing CPR. For two hours, paramedics, then doctors performed CPR. Their efforts weren’t enough, and Sammy was pronounced dead. For his parents, this was “the worst hell.”

“His younger brother, three years ago, had a seizure,” Craig Berko, 48, of suburban Houston, tells TODAY.com. “Frankie was dead and unfortunately he didn’t come back. Now going through this again with his older brother … it was really hard.”

The doctors cleared the room so the Berkos could say goodbye to Sammy and something amazing happened — Sammy moved.

“A couple times, he moved his chin upwards to try to get a breath,” Jen Berko, 45, tells TODAY.com. “My husband screams, ‘We have a heartbeat,” and the whole team came running at full pace back in because they were in disbelief.”

A day of fun turns tragic

On Jan. 7, Sammy joined friends at a local rock-climbing gym. The teen volunteered to be the first to scale the wall. At the top, he rang the bell, but he suddenly became “completely limp.” His friends thought Sammy was joking before realizing he was unconscious. When Sammy reached the ground, someone rushed over and started performing CPR. The Berkos later learned that he was a radiologist and he provided “high-quality CPR” on Sammy. When the ambulance arrived, paramedics took over and when Sammy went to the hospital, the staff continued. For two hours, the medical tried to revive Sammy.

Finally, doctors pronounced Sammy dead and the Berkos said goodbye.

“We were just talking to him, telling him how much we love him, how proud we are of all that he is and that he has accomplished and that we were just so sorry that we weren’t able to save him,” Jen Berko says. “I started praying.”

Then Craig Berko saw him move.

“My husband said, ‘Oh my God, he just moved,’” Jen Berko says. “The main attending doctor poked his head in and said it’s probably just a reflex.”

Jen Berko saw Sammy's neck turn purple and his carotid artery move as if his heart was beating. Craig Berko yelled about Sammy’s heartbeat and the team rushed into the room.

“No time was wasted,” Jen Berko says. “They did everything possible to get him stabilized. It was unreal.”

For the Berkos, this moment felt even sweeter. It seemed Sammy was getting a second chance at life that their son Frankie never did.

“I was a former fireman, and I was the first responder,” Craig Berko says. “I was giving Frankie CPR but tragically he never came back.”

Doctors thought that there might be a link between the Frankie’s and Sammy’s deaths. They test remaining tissue from Frankie as well as Sammy's to try to uncover the connection. Meanwhile, Sammy still faced a lot of challenges. He was in the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) struggling to survive.

“It was a very long night trying to keep him alive,” Craig Berko says. “His organs were massively failing, and we were told by the doctors that he’s probably going to be brain dead.”

Sammy was on a ventilator and “lost all neurological signs except for his eyes remained ... reactive.” Again, the Berkos found themselves at their son’s bedside praying and pleading for him to live.

“I whispered in his ear. I said, ‘Maybe people think that you can’t hear me right now, but I know you. I don’t believe that for one second because you’ve already proved them wrong by coming back to life downstairs in the ER — and I know you’re going to do it again,’” Jen Berko says.

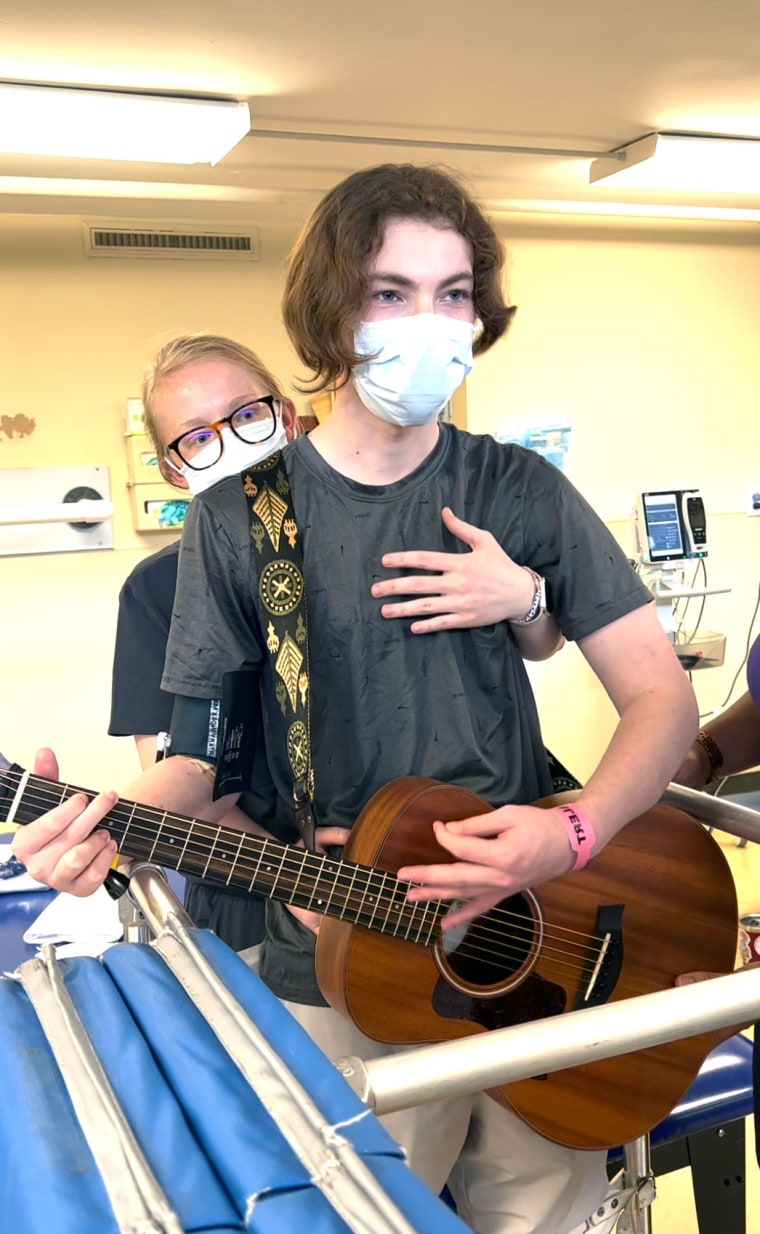

Doctors put him on dialysis and the family continued supporting Sammy by playing music next to his ear. Sammy loves music and plays guitar, piano and drums. Then Sammy’s eyes moved.

“It seemed like he was reacting to my wife’s voice,’” Craig Berko says.

At first, doctors thought it might be a reflex. To be sure, the doctor asked Sammy questions and instructed him to blink in response.

“He started responding,” Craig Berko says. “The attending doctor was like, ‘This is unbelievable.’”

Hours later, Sammy opened his eyes and started fighting the medically induced coma.

“He wanted to be awake so badly,” Craig Berko says. “His zest for life was so strong that he kept fighting through the medicine and kept fighting to get back to us.”

Over the next four weeks in the PICU he gradually improved. He had experienced strokes in his brain and spine that caused memory problems and paralysis from the waist down, respectively.

“The doctors later told us after the fact that the CPR Sammy received must have been stellar CPR,” Jen Berko says. “That is why he doesn’t have a catastrophic brain injury.”

Then he went to a step-down unit before going to a rehabilitation hospital. While Sammy has feeling in his legs, he has no movement.

“Unfortunately, there’s no correlation between feeling and moving to different parts of the spine,” Craig Berko says.

The family also learned why both Frankie and Sammy died. They had a rare genetic condition called catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (CPVT). Their mother, Jen Berko, also has it.

“While doctors say it’s incredibly rare, it’s still, relatively speaking, a new disease,” Jen Berko says. "They’re still learning how to treat it."

What is CPVT?

Mutations in certain genes, either RYR2 or CASQ2, cause CPVT, which leads to irregular heartbeats that can be deadly, according to the National Library of Medicine. Both the endocrine and cardiovascular systems contribute to CPVT, as TODAY.com previously reported.

When people workout or feel frightened and experience a fight-or-flight reaction, their bodies release a neurohormone called catecholamines. This causes that increased heartbeat people feel when scared or during an intense bout of exercise. When catecholamines release in people with CPVT it triggers an irregular heartbeat also called ventricular tachycardia and that prevents normal blood flow, Dr. Neil Cambronero, an associate surgeon at Texas Children’s Hospital told TODAY.com in February. Treatment often involves preventing catecholamines from flooding the body.

“I’m on both a calcium channel blocker and a beta receptor blocker and that helps block the adrenaline rush to the heart and regulates the heart rhythm,” Sammy Berko tells TODAY.com. “So you can help prevent an event.”

Sammy also underwent a procedure called a sympathectomy, where doctors neutralize a nerve that “runs from your heart to your brain that communicates the adrenaline rush,” Jen Berko says.

“It will reduce the likelihood that an adrenaline rush would cause cardiac arrest,” she says. “The toughest thing is nothing is 100%.”

Sammy might also need an internal defibrillator, which would shock his heart if it went into an irregular rhythm. But the doctors are still debating it, the family says. Right now, he wears a LifeVest, which is something external that will shock him if he goes into arrhythmia.

Navigating recovery and rehab

Dr. Stacey Hall, the medical director of the pediatric rehabilitation program at TIRR Memorial Hermann, was one of the doctors involved in Sammy’s care.

“He’s doing amazing,” she tells TODAY.com. “For any prolonged CPR we are generally anticipating that they have catastrophic global anoxic brain injury. It’s highly unusual he’s doing as well as he is.”

She says that the high-quality CPR received helped prevent more extensive damage. While in rehab, Sammy worked on building his strength so he can stand and move with a walker. He also had to relearn how to do everyday tasks, such as dressing, showering and going to the bathroom with a wheelchair. His attitude helped him flourish.

“He was super highly motivated,” she says. “He has an amazing attitude especially for a teenager that went through this.”

While Sammy has returned home, he still has a lot of outpatient rehabilitation ahead of him.

“Things he will continue to work on are strengthening his legs, working on walking,” she says. “I can tell you for sure that regardless of whether or not he is walking, he can do amazing things.”

Sammy’s been taking all the changes in stride.

“It’s been insane to see all the progress that I’ve made,” he says. “It’s quite a lifestyle change at least to be in the wheelchair and monitoring my heart.”

The Berkos hope that genetic testing for CPVT becomes more widely available so more children can be screened for it before they potentially experience cardiac arrest or death. The family’s experience with death has put life into perspective.

“You can’t take life for granted,” Craig Berko says. “(With Frankie) we’re having a good day and all of a sudden, boom, he’s gone. Life is really short and fragile.”