In late November, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention shared a staggering statistic: Provisional data from the National Center for Health Statistics indicated that for the first time in the U.S., drug overdose deaths had reached over 100,000 in a 12-month period.

It's a topic close to Christine Marsh's heart — and political goals. When Marsh (D-AZ), a former high school English teacher, began running for state senator of Arizona in 2019, she also started researching a topic that was affecting her state: the opioid crisis. In her findings, she learned of fentanyl, a powerful synthetic opioid that is similar to morphine but is 50 to 100 times more potent, according to the National Institute on Drug Abuse. Often users don’t know they are taking fentanyl, as drug dealers cut other popular drugs — including MDMA, cocaine and prescription pills — with it because fentanyl is a cheaper option that produces a similar high.

“I did not know the extent of how frequently fentanyl is being woven into these other drugs,” Marsh said.

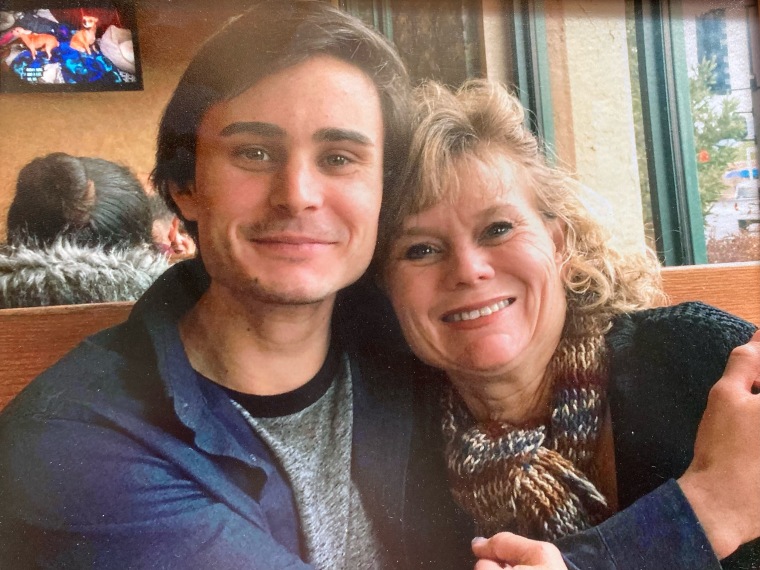

During her research, Marsh also discovered fentanyl testing strips, a tool that can be used to detect the presence of the synthetic opioid in other drugs, deterring some people from using at all. She learned of the life-saving tool too late: Her youngest son, Landon, died of an overdose on May 18, 2020, after a night out with one of his best friends.

“He had gotten married about three weeks earlier,” Marsh explained. “He was getting a mechanical engineering degree. By all accounts, he was not into drugs. He wouldn’t even take allergy pills and I know because I had the unfortunate task of going through all of his stuff. But he had a wild night out with a childhood friend and they bought a Percocet that had fentanyl in it. It killed him.”

Landon was 25 years old.

From there, a political talking point for the Arizona woman became deeply personal.

“We want people who are battling addiction, or even just taking these illicit drugs recreationally, like my son was, to not do drugs and to get the help they want, but we need them to live long enough to do so,” she said. “The testing strips for fentanyl is one more tool for that.”

TODAY spoke with advocates and activists who say despite their effectiveness as a useful tool in harm reduction against fentanyl, awareness around testing strips is lacking and in some states they are even considered illegal.

How do fentanyl test strips work?

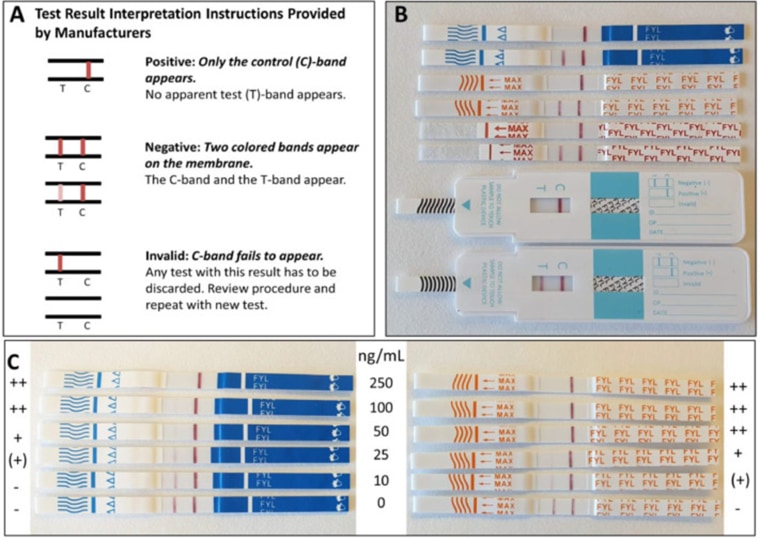

Fentanyl testing strips are often compared to pregnancy tests in terms of how they work and how a user will receive results. Originally intended to test for the drug in urine, the strips are now more commonly being used to test the actual drug supply.

A small portion (about the size of a match head or half of a grain of rice) of an unregulated drug is added to water. Then users will swirl the substance around until it is completely dissolved and dip the small paper strip into the water. Two solid lines indicate there is no fentanyl present, while one line indicates the substance is present. Some users may dilute an entire pill or larger portion of the unregulated drug.

A recent study from the International Journal of Drug Policy tested four brands of urine fentanyl test strips for drug solution testing. All of the strips were successful at detecting a broad panel of fentanyl. A 2018 study from researchers at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Rhode Island Hospital and Brown University, found that low-cost test strips (specifically the BTNX branded strips) detected the presence of fentanyl with a high percentage of accuracy.

However, the strips aren't a perfect tool, noted Jennifer Carroll, an assistant professor at North Carolina State University and an adjunct assistant professor at Brown University who researches substance use and public health.

"(Fentanyl test strips) have a really low limit of detection, which means that they will be able to give you a true positive when fentanyl is present at a very low concentration ... (but) it has some limitations in that it has a few risks of a false positive," said Carroll. "For example, if Benadryl is present, which is sometimes used to cut a drug, or methamphetamine is not diluted enough, it can return some false positives."

Harm reduction experts are in favor of the strips because they're relatively inexpensive, portable and easy to use.

"It takes a very little amount of drugs (to test), so people, if they're worried about having to give away their drug to be able to see whether (fentanyl) is in it or not, that isn't the case," Carroll said.

Do the strips actually deter use?

After a test strip detects fentanyl, a user still has the choice to use the drug. Some argue that most will still continue to use. In fact, it's important to note that some users do seek fentanyl because it's a stronger and cheaper drug. Yet for any kind of user, these strips could be a helpful tool.

A 2019 study conducted in North Carolina found that among individuals who used a fentanyl test strip before using drugs, those who received a positive result for the presence of fentanyl had five times the odds of reporting changes in drug use behavior like using less, not using alone or not using at all.

Emanuel Sferios, the founder of DanceSafe, a peer-based education and harm reduction organization that has testing strips available for purchase online, said that he and the volunteers who work at his organization see that the especially impressionable populations of teens and young adults are particularly impacted by the testing strip results.

“We’ve been testing drugs for young people since 1999 when I founded DanceSafe and I can tell you as a fact, neither I nor any of our hundreds of volunteers have ever seen anyone take anything that tested positive for fentanyl,” Sferios said.

Dr. Kimberly Sue, the medical director of the National Harm Reduction Coalition, an advocacy organization promoting health equity for those impacted by drug use, believes the strips could deter some people from using. Sue believes the strips are particularly useful for recreational users who don’t regularly take opioids. The presence of fentanyl would be extremely dangerous for this population because their bodies are not used to any opioids, let alone those laced with the more powerful synthetic version.

“They have no physiologic tolerance, meaning their body’s not used to it,” she explained. “People are at increased risk of overdose when fentanyl is present in their substance.”

Yet for those who continue to use a substance that contains fentanyl, the strips are still a harm-reducing tool.

"It might deter some folks from using, if they do not wish to use a substance with fentanyl or (it) could help them to use it more slowly or in safer ways, like with people who have and are trained to use naloxone in case of overdose," Sue explained. “They’re using in a way that’s educated and informed that could potentially keep them safe from overdose or death. ... There’s no way that this use, having access to this technology in any way harms people.”

Why aren't the strips more widely used?

Sue points to outdated public policies and laws.

“You look at our opioid overdose deaths in this country and 'Just Say No' has failed. It has led to so many deaths. People don’t know what to do,” Sue told TODAY.

Traci Green, a professor and director of the Opioid Policy Research Collaborative at Brandeis University, agreed, citing 1970s-era drug paraphernalia laws that aimed to target marijuana distribution. According to research conducted by TODAY, the strips are only fully legal in 13 states.

"The idea that someone having a fentanyl test strip is indicative of a large scale distribution is kind of ridiculous, right?" asked Green.

“Many patients are afraid (to use them)," Sue said.

Proponents of drug prevention-based education stress that there is not one method or policy to solve this complex issue.

“It (needs to be) a kind of cumulative, comprehensive approach that’s going to be successful — involving intervention, apprehension, prevention and treatment,” said Frank Pegueros, the president and CEO of DARE. “It’s not going to be successfully addressed by a single effort. It has to be a multifaceted approach.”

In April, the CDC and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration announced that federal funding may now be used to purchase fentanyl test strips to help curb the spike in drug overdose deaths.

You look at our opioid overdose deaths in this country and ‘Just Say No’ has failed.

Dr. KIMBERLY SUE

But where can users get the strips?

“Harm reduction programs around the country have access to (the strips),” Sue said. “People can buy them online from DanceSafe.”

How to raise awareness of fentanyl testing strips

Sferios stresses parents need to have conversations with their children about drugs, especially when trying to keep them safe from fentanyl.

“How do you get parents to speak openly about drugs with their kids? The first thing they should do is admit their own drug use or their own past use,” Sferios suggested.

Sferios knows this because he is a stepfather of two teenagers himself.

“When my stepdaughter started getting exposed to drugs at 13, she was able to come and talk to us openly about them and how to use them safely, because we acknowledged to her what we did when we were younger,” he said. “... We have this fear ourselves — the judgment other parents will have once they find out we’re talking to our kids about drugs.”

Sue also stressed that parents should approach the topic of recreational drug use with their children the same way they may approach the topic of underage drinking.

“Wouldn’t you want to equip your children (in the same way) you might educate people about alcohol?” she asked. “People know that their kids are going to drink at this party so they say, ‘Make sure to eat, please watch out for each other, please call.’"

"If you take a kind of a practical standpoint, where you encourage children and teenagers and their friends to be open and you create a safe space for them to talk about what they’re doing, people will tell you and engage with you," she continued. "It’s when you moralize, it’s when you use ‘Just Say No’ … that you have these quote unquote tragedies that are all preventable.”

Sue also encourages parents to talk to their kids about watching out for one another, having naloxone — a medicine that rapidly reverses an opioid overdose — taking turns using and to call 911 in case of emergencies. There’s also the Never Use Alone hotline: an organization that provides a contact for people using drugs alone “to help increase their odds of surviving an overdose or fentanyl poisoning,” according to their website.

“People need to know about these resources,” Sue said. “If people activate all of our collective resources around this issue, and we take it out of the shadows and we stop having this kind of secrecy and misunderstanding about substance use ... many lives would be saved."

‘One pill is too many’

Before her son Landon died, Marsh was already fighting to get fentanyl testing products decriminalized in the state of Arizona. The strips fell under the state’s umbrella of prohibited drug paraphernalia, in the category of equipment that identifies the strength and purity of drugs, which were banned under state law.

However, one year after Landon’s death on May 18, 2021, Gov. Doug Ducey (R-AZ) signed Marsh’s bill — Arizona's Senate Bill 1486 — into law, exempting the test strips from the state’s definition of prohibited drug paraphernalia.

“I knew the bill was going to need to be not a big sweeping change, but something more smaller and more doable,” Marsh said of the bill's bipartisan marketability. “Part of passing this bill has been just trying to raise awareness of this issue. We come to the point where one pill is too many, one pill can be and often is, as it turns out, a death sentence.”

“On the broadest scale, I really hope that other states for whom these testing strips are illegal are investigating passing similar legislation,” Marsh said. “On a more local level here in Arizona, the next step for me is to get these testing strips into more people’s hands. My ultimate goal would be to have these available at your corner drugstore. You can go in and buy those testing kits for urine. Those have been available at the corner drugstore for many years. I would love to see these testing strips there as well.”

On remembering her son, Marsh gets emotional extolling his virtues when asked to share a favorite memory.

“I’m his mom so I’m biased, but he was the smartest, most out-of-the-box thinker that I had ever met,” she said. Marsh believes that if her son knew about fentanyl testing strips that night when he went out with his friend, he would have used them.

Marsh hopes that all people of all ages are empowered with this tool and the information it can provide.

“These interviews, quite frankly, are hard. I mean, talking about my deceased son is no easy feat. But in my mind, every interview like this has the potential to save a life or few lives,” she said.

"I have no doubt that he would be very approving of the fact that I am desperately trying to save other people from the fate that he faced.”

CORRECTION (Dec. 30, 2021, 12:34 p.m.): An earlier version of this article misstated the name of the DanceSafe founder. He is Emanuel Sferios, not Mitchell Gomez.