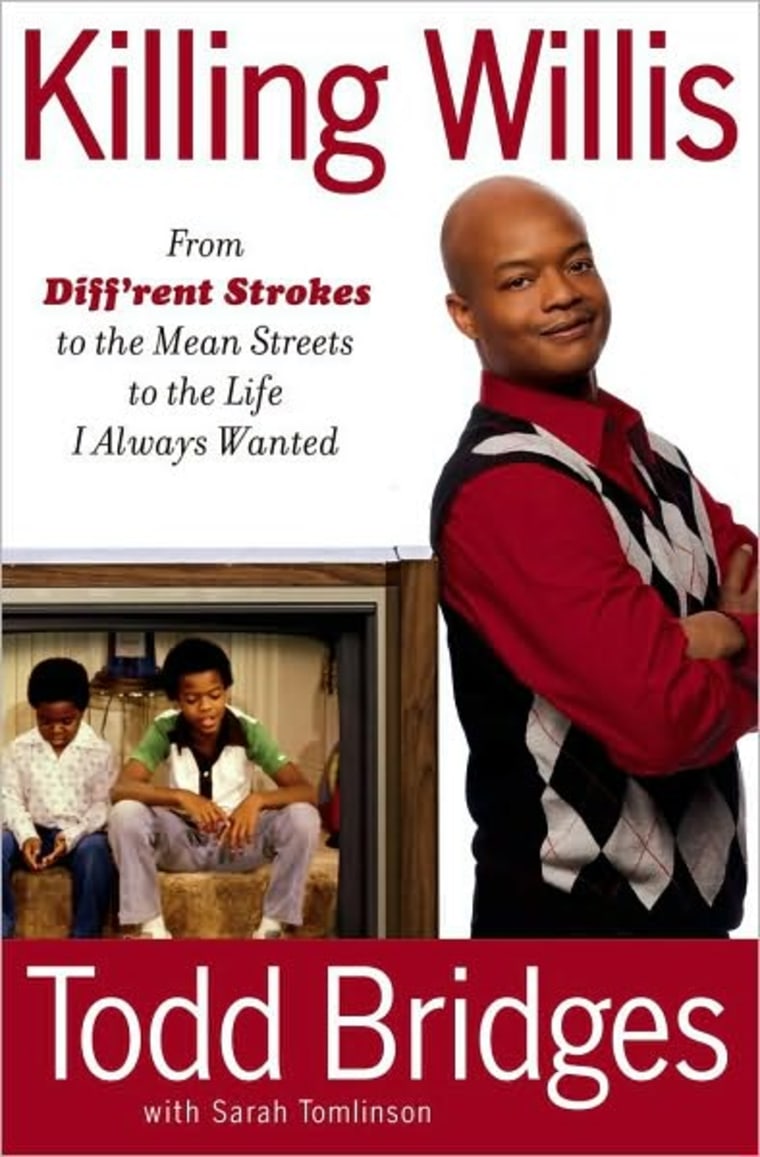

In his memoir “Killing Willis,” the actor who played Willis on the sitcom “Diff’rent Strokes” writes about hitting his lowest point — selling crack and meth and getting busted by the police. An excerpt.

Chapter one

Suicide by cop. It was my only way out. I couldn’t see any other solution. I didn’t care enough about myself or anything else to find another answer. Officers from the Burbank Police Department had pulled me over on a residential street. I was on my way back from scoring drugs for a girl I knew, and I had a sixteenth of speed in the hiding place in my car. Their squad cars were parked close behind my Mercedes, with their lights flashing, sirens blaring. They were out of their cars now, coming up on me, their weapons drawn and held steady, right at my head.

I reached for my gun.

This was December 29, 1992, and I was worn out. It’d been a long time coming. I’d been using and dealing on and off for six years, and even though I’d been trying to get my act cleaned up, it clearly wasn’t working. I decided to give the cops what I knew they wanted, the chance to say they’d taken down Todd Bridges, the former child star turned drug dealer, whether they got me with bullets or with bars.

I never would have let myself get caught with drugs in my car before. When I was a serious dealer of crack and methamphetamine, I dealt to supply my own addiction to both. Being high made me more alert, and I was high all the time. Sometimes things got real weird, and I felt like I was living in one of the movies I had acted in during my old life. But I always knew when the cops were watching me, and I kept my stuff well hidden.

The drugs and dealing had been exciting for a while. But more importantly, they had kept me numb. They made me forget all of the bad things that had happened to me as a child. On the outside, I’d had it all, living the life I’d always dreamed of as a TV star with a lead part on the hit shows “Fish” and “Diff’rent Strokes.” But that wasn’t the whole story.

On the inside, I’d been left with dark memories that overpowered the good. I didn’t want to feel the pain I’d carried with me from my childhood into adulthood, and so I didn’t want to stop using drugs. But I couldn’t keep on going like I was. I kept trying to do the right thing, like my mom had taught me, like I had been told in church when I was growing up, like I knew I should. But my life was so crazy that any attempt I made to be a decent human being only seemed to land me in another whole mess of trouble.

A few months before my run-in with the Burbank Police, I’d met this girl, Tiffany. With me, there was always a girl involved somehow. There was something nice, almost normal, about this particular girl. She was mulatto, medium height, and curvy. She had this reddish hair that she wore short and spiked. She started hanging around, and pretty soon we were dating. I guess that’s what you’d call it. I wasn’t exactly the kind of guy who sent flowers back then. But we were together a lot, just doing whatever. And even though she was using drugs herself, she was supportive, in her own way, of the fact that I was trying to get my life together.

I was done with how crazy the drugs made me: the paranoia, the hallucinations, the feeling that maybe if I had to draw my gun on somebody, and then, if he drew his gun and shot me to death, it’d be for the best. I didn’t think my mind or my spirit could take much more.

I quit meth. I quit crack. I basically quit selling drugs. I had a little money that my mom had kept safe for me during the years I had gotten heavily into drugs, and I just tried to live something like a normal life.

But getting out wasn’t that easy. Not after I’d been so deeply involved for as long as I had been. On the day of my run-in with the Burbank Police, I was in my house in Sun Valley when I got a phone call from this other girl, Joelle, I’d hung around with for a month or so, about seven months earlier. I knew I shouldn’t be taking calls from other girls when I was seeing someone, so I went into the other room to keep Tiffany from hearing my conversation.

There was no way I was going to not take this call. Joelle was something else. She was the one who got me hooked on methamphetamine. The first time she ever shot me up with meth, the high was so good, I came. I was hooked on the drug, and I was hooked on her. She was a pretty girl — blond and very voluptuous, with a great body for a drug addict — and very wild, sexually, just nasty and crazy. It was always real intense with her, real on the edge, and I never knew what was going to happen next. So when I heard her voice on the phone that day, all sexy and suggestive, that’s all it took to get me excited.

I knew Joelle was dangerous, but I wasn’t thinking too clear right then.

“Can you get me a sixteenth of speed?” she asked.

“No, I’m not doing that anymore,” I said, keeping my voice down.

“Well, can you just go find somebody to get it for me?”

Her voice was real flirty-like. I knew if I did her a favor, I’d get something good in return. Girls who needed drugs would do anything. That’s how I liked it.

“Yeah, okay,” I said. “Where do you want me to meet you at?”

We worked out a plan where I would meet her in Burbank to get the cash to buy the drugs, go buy them, and then hook back up with her in Burbank. If there was one thing I had learned, it was to never buy drugs for someone without getting the money up front. People were always trying to pull something. And if she didn’t pay me for the speed once I bought it, it would be worthless for me to hold out on giving it to her, since I wasn’t using anymore. What I cared about was how she was planning to say thank you. I had a few ideas in mind.

Like I’ve already said, I wasn’t really dealing anymore, so I didn’t have any drugs on me. I called a friend of mine and arranged to meet him at his place in North Hollywood to get some speed for Joelle. Then I drove from my house to meet her, and then, from there, to my buddy’s house. While I was driving, I totally forgot about the cops who were following me.

This was not easy to do. The cops had been a constant force in my life since I was fifteen. That’s when my family moved to the San Fernando Valley. The police force started harassing me, pulling me over, calling me a nigger, and finding any excuse they could to hassle me until I came to hate the color of my own skin, almost as much as I hated the police. They’d arrested me plenty of times since I’d gotten into drugs, and they’d been following me pretty much nonstop for the past two years. In fact, my good friend Shawn Giani, who was my neighbor in Sun Valley for many years, had called me and tipped me off that the cops had asked if they could watch my house from his bushes.

At the height of my meth use, I got so messed up on drugs that I went out to their undercover van and started banging on it, shouting, “I know you’re in there!” There was a guy in there, all right. He took one look at me, climbed up into the driver’s seat, and drove away. But that wasn’t the last I saw of him.

Whatever I was doing, I could count on the fact that there was always a cop somewhere nearby. When I was on meth, no matter how high I was, I knew the police were out there. And I was always able to avoid them. Even when I was doing fourteen grams of meth a day, and so high I was having hallucinations, driving around with drugs and loaded guns in my car, dropping off and picking up the girls I had working the streets for me, the cops never caught me.

But on that day in December, I smoked some pot, and pot made me stupid, real stupid. It was the only thing I was doing since I’d quit crack and meth. It should have been an improvement, right? It would have been, except for the fact that on pot, I was a total moron. That made me an easy target. I didn’t care that the cops were following me because I didn’t know. I had forgotten that cops even existed.

Get this, though. Even though I was driving around in the stupidest marijuana haze possible, the cops somehow managed to lose me. Maybe that says something about all of the times the police didn’t catch me when I was doing something illegal. After they got separated from my Mercedes, they pulled their squad car off the road and two officers ran into a Ralph’s grocery store, looking for any sign of me.

They happened to stop a lady who knew my mother.

“Have you seen Todd Bridges in here?” they asked her, thinking she’d be able to recognize me from TV, not knowing she was a family friend.

“No,” she said. “He hasn’t been here.”

After checking the store, the officers jumped back into their squad car and drove away. As soon as they were out of sight, that lady ran to a pay phone and called my mom. “They’re looking for your son,” she told my mom.

My mom wasn’t at all surprised to receive a call like that. She’d prayed, and cried. She’d come to family therapy sessions when I was in rehab. She’d bailed me out of jail when she could, and visited me in jail when I was denied bail. But nothing had done anything to turn me around. At the time, I was so far gone that I couldn’t register anything beyond how low I was feeling about myself, and how the drugs — whether it was crack or speed or pot — made this pain go away. I couldn’t hear what she was saying when she begged me to get sober, and I certainly couldn’t understand how much I was hurting her. But no matter how dark my life got, my mom never gave up on me. When she learned that the cops were after me, she called my house. And when she got the machine, she left a message for me.

“Whatever you’re doing, stop it now. The police are looking for you.”

I didn’t ever get that message.

By that point I was on the way back from my friend’s house with a sixteenth of speed, totally ignorant of all of the excitement I’d been causing across the San Fernando Valley. I had the drugs, and I was going to see a sexy girl who would be very glad to get them. That’s all that mattered to me. My gun was in the secret hiding place I’d made in the dashboard of my car. It was right below the radio. There was a button that looked like it controlled the car alarm, but when you pushed it, a secret compartment dropped down. I was good at hiding places. There were plenty of times the police searched different cars I owned over the years, but they never found my drugs or my gun.

The police hadn’t given up searching for me. Far from it. They picked me back up. As soon as I heard the siren, I knew they had me. I pulled over. They came out of everywhere. And they made it clear — they weren’t playing.

“Get out of the car, right now!” one of the officers yelled at me, his gun drawn.

Behind him, the officers from the other squad cars and the undercover van stood at the ready, legs wide, guns drawn. A drug dog barked and tugged at its leash. I had been through this before. My trial for attempted murder in ’89 was big news. The headlines that ran on TV and in the tabloids were plenty nasty. I’d had to go through it again a year later, when they retried the case.

I couldn’t face it all over again. I was totally demoralized.

I hit the button and opened the secret compartment where my gun was hidden. I had a 9mm Beretta in there, and I put my hand on the grip.

“Forget it,” I thought. “Just kill me now, because I’m tired of this life anyway.”

I was ready for it all to end. I was done with the hurt and the shame I felt over the abuse and racism I had experienced as a child, the feeling I had that my life wasn’t worth anything, and that because I was a drug addict, I didn’t deserve any better anyhow.

The cops were ready, too. They watched me closely.

But then something spoke to me from deep inside of myself, maybe God, maybe some part of me that had somehow managed to survive all of the bad stuff I had been through and wasn’t ready to give up, no matter how much pain I was in.

“Don’t reach for it,” the voice said. “Just let it go.”

It was a hard choice. Suicide by cop was easy compared to what I had in front of me. I had gone from being a teen idol to a tabloid joke. I was broke, and I didn’t have any prospects of getting my career back. I had been to rehab five times. I usually didn’t last more than a few days. It never once stuck for longer than a few months. I had spent almost a year in jail while awaiting trial and vowed I would never go back. I had tried, and failed, to block out all of the things that had been written about me in the press before. I had felt pain and self-hatred so deep and raw that the only way to silence it was with drugs.

But this was not how I wanted to end it. I wanted to live. I let go of my gun and closed up the secret compartment.

Now that I didn’t want to die, I was scared that they were going to kill me. The cops in the San Fernando Valley had abused me so much as a teenager that I finally filed a police harassment lawsuit in the mid-’80s. It only made them hate me more. And now they had their guns drawn and plenty of reasons to use them.

I kept my hands visible as I opened the car door slowly, careful not to spook them. I got out of the car, trying to act cool. Everything went crazy after that. The sirens ripped through my skull. The drug dog leaped toward me, barking even louder. I rested my hands on the back of my head to show I was cooperating and backed up toward them, trying not to imagine being shot in the back. The police were all over me. They rushed up, shouting orders, their guns at close range.

The undercover officer whose van I’d ambushed when I was out of my mind on drugs came up and put his gun to my head.

“I’ve got you now, mother------,” he said.

I wasn’t exactly in a position to argue.

They grabbed me, got me onto the ground, and held me there. They patted me down and let the dog go over me. I was wearing baggy Cross Colours clothes, which young black men were really into at the time, and they checked all of the pockets for weapons and drugs. When they cuffed my arms behind my back, I knew it was all over. As they put me in the back of a squad car, I actually felt a sense of relief. I hated my old way of living so much that I had been ready to die. And now I had a chance at something better, if I could only hold it together this time.

I didn’t realize it then, but it was ironic that the Burbank Police Department was the one to arrest me and, ultimately, save my life. When I was at the height of my career as one of the stars of “Diff’rent Strokes,” I received a plaque on October 13, 1979, “In Appreciation for Services Rendered to the Burbank Police Officers’ Association.” Nothing could be a clearer symbol of how far I’d fallen since then. Gone was the cute kid who had made people laugh on TV and used his fame for good by visiting veterans, children’s hospitals, and public schools. In his place was a shell of a man who was so sick in body and mind that he had almost given the officers who had honored him a good reason to shoot him to death.

When the cops searched my Mercedes, they found my gun and the speed. They knew right where to look. Not too many people were aware of my secret hiding place. But Joelle knew. I was sure she had set me up.

I wanted to kill her. I would have, too, if I’d seen her right then. My mind was still all screwed up from the drugs and everything I’d been through.

But I was tired of feeling like that, of living in a world of drugs and guns, where surviving meant getting the other person before he could get me. I felt lucky that I had made it out alive. I was going to at least try to stay that way. I basically told the officer everything. Ironically, there wasn’t much to tell, not like if they had arrested me a year earlier. Since I had quit using hard drugs, and pretty much quit dealing, my life was fairly tame. But there was enough to keep me in jail.

I called up my lawyer, Johnnie Cochran, who went on to make his name defending O. J. Simpson during his murder trial. Johnnie came down and sat next to me in the cell. He rolled his ring around on his finger, thinking, before he spoke.

“I’m going to tell you what,” he said. “This is the last time I’m going to help you with anything. If you don’t straighten your life out, I’m done. Don’t call me. Don’t be my friend. I don’t need you in my life if you can’t straighten yourself out.”

Johnnie had always been there for me. My family and I first hired him to represent me in my lawsuit against the LAPD. This was after their years of discrimination came to a head when they tried to arrest me for supposedly stealing my own car. He had represented me in my attempted-murder trial in ’89. And when my own father didn’t visit me, even once, while I was in jail for nine months leading up to that trial, Johnnie had been like a father to me. The thought of not having him there to help me anymore filled me with panic.

“You know, Johnnie,” I said, “I’m ready to stop. I just need to know how.”

“Well, you need to figure out how to do it,” he said.

That was the problem. I didn’t even know how to start.

I was bailed out of jail a few hours later. I went home, and even though I had the desire to turn my life around, I couldn’t. I started getting high again right away, and not only on marijuana either. I was back on meth and crack. Like I had told Johnnie: I didn’t know how to stop. I stayed high for the next few months, until I had to go back to court. I probably would have felt bad about letting Johnnie down, and about letting myself down, and about letting my mother and everyone else in my life down. But when I was high, I didn’t feel anything. That was the whole point.

Excerpted from "Killing Willis" by Todd Bridges. Copyright (c) 2010. Reprinted with permission from Simon and Schuster.