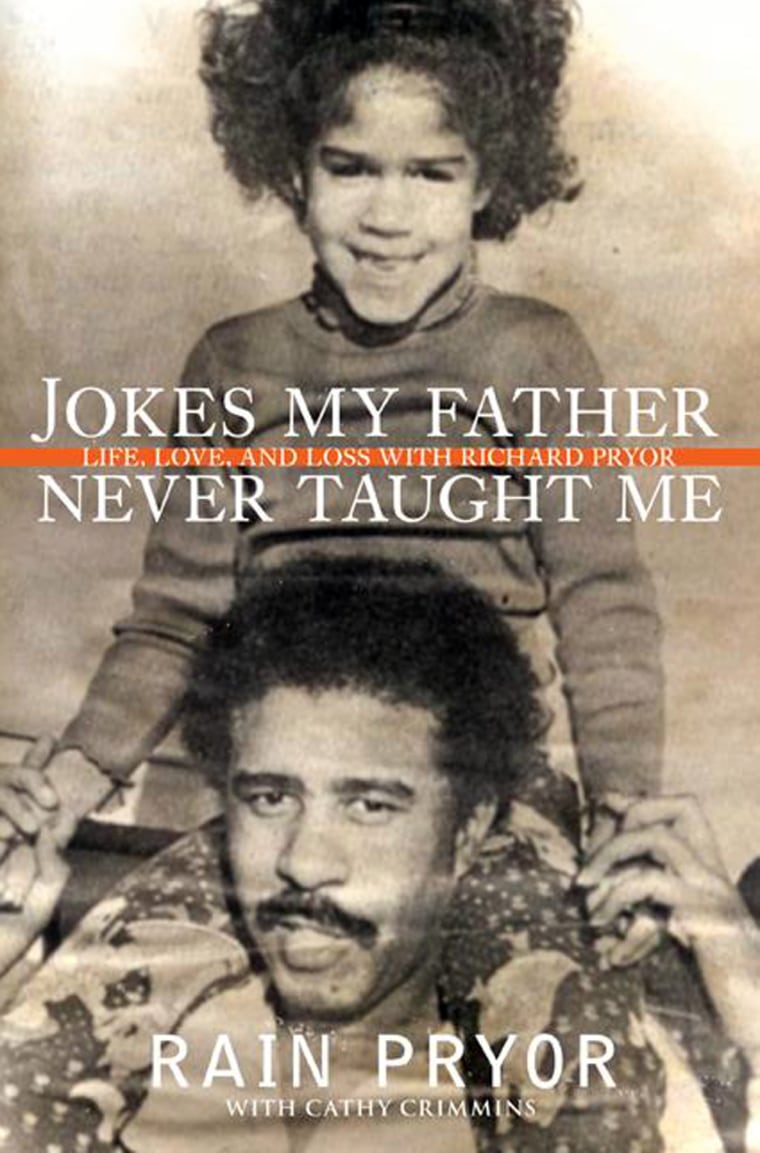

You could always count on a good laugh from Richard Pryor. His daughter Rain Pryor has written an autobiography about growing up with him in her new book, “The Jokes My Father Never Taught Me.” Rain Pryor was invited on “Today” to discuss her book. Read an excerpt

Chapter One

Home at LastIt was one of those rare Los Angeles days when the ocean fog lifts early and the smog never appears. The baby blue sky sparkles, calm and cloudless, and you can see the sharp outlines of the houses clinging to the Hollywood Hills.

The year was 1973 — I was four years old — and my mother and I were in her battered Volvo, winding our way toward those hillside houses. I had no idea where we were going, and my mother wasn't talking.

"Are you going to tell me now?" I said.

"Stop bugging me," she said.

"I just want to know where we're going," I said.

My mother took a deep breath, gave me a dirty look, and exploded: "We're going to meet your father, okay?! Happy now? We're going to meet your m***********g father."

That was a lot to process for a four-year-old. The language didn't bother me — I was used to it — but I was having trouble getting my mind around the fact that my father lived only a few miles from our own apartment. "My father lives here?" I asked. "In the same city?"

"Where the fuck did you think he lived? On the m***********g moon?"

Frankly, that was a possibility. I had heard many stories about my father — most of them pretty unflattering — and I never imagined that some day I would become part of his life. He was a famous comedian, after all, and I'd been given to understand that comedy took precedence over fatherhood. What's more, he happened to be a self-destructive, self-absorbed schmuck, and he wasn't even remotely interested in me. That's what my mother told me, anyway — that and worse. Whenever she talked about him, and she talked about him often, she would work herself into such a frenzy that she would turn red in the face. Her parents, my Jewish grandparents, also talked about him. They didn't curse with quite as much vigor, and they didn't turn red in the face, but they made no secret of their feelings for the crazy Black Prince who had ruined their daughter's life (and, in many ways, their own).

"I'm going to meet my father?" I asked.

"Didn't I just say that?"

"He lives in one of these nice houses?"

"That's right. The son of a bitch lives in a f******g palace, and we live in a dump in the wrong part of Beverly Hills."

"Why is it the wrong part of Beverly Hills?"

"Would you give me a goddamn break already?!"

I didn't understand what she was so upset about. Earlier that afternoon, when we were in the house, preparing to leave, my mother had seemed excited, if a little nervous. She said we were going "somewhere special," and told me to wash up and put on a nice dress and to try to look pretty. When I returned, fully dressed and looking awfully pretty (if I may say so myself), she was still in her jeans, topless, tearing through her closet for just the right thing to wear. I guess she wanted to look pretty, too, but nothing made her happy. I watched her try on one blouse after another, growing increasingly frustrated, until there was a veritable kaleidoscope of blouses piled on the bed. She had practically emptied the closet by this time, so she went back to the bed and sifted through the discards, hoping she had missed something. She tried the purple dashiki again, then the severe black knit sweater with the bell sleeves, but neither of those worked. Finally, she opted for my very favorite: a yellow and red Mexican peasant blouse with embroidered flowers. She buttoned it up, tied up her hair with a red silk scarf, and turned to look at herself in the mirror.

"M**********r!" she said.

"What did you say, Mommy?"

"Nothing," she snapped. "Let's go."

We went out into the street and moved toward her old, sad-looking Volvo. She opened the rear door and motioned with her head. "Get in," she said. I did as I was told, and as she strapped me into the backseat, I noticed that her hands were shaking. I wanted to ask her if something was wrong, but she didn't seem like she was in the mood for questions, and I didn't want to make her mad. I hated it when she got mad, and she got mad often. She shut my door, hard, then climbed behind the wheel, started the car, and pulled out into the street.

We rode in silence for a while, each of us alone with our thoughts. The Volvo chugged across Robertson Boulevard, took a right on Sunset, then a sharp left into the winding hills.

When she finally told me that we were going to visit my father, I was more confused than ever. I couldn't believe that my father actually lived in Los Angeles, way up in those lovely hills, just a few miles from our shabby little duplex. I couldn't understand why we had never visited, or, conversely, why he'd never come to see me.

"Did he just move here?" I asked.

"No," she said. "He's always been here."

"Do I look like him?"

"Stop with the f*****g questions already!"

I looked out the window again. The houses were unlike any houses I'd ever seen — big rambling places nestled into canyons, only vaguely visible behind trees and walls and tall gates.

The Volvo kept climbing, negotiating one hairpin turn after another, and after what seemed an eternity we reached a gate at the top of the hill. We'd only gone a few miles, but I felt as if I were embarking on a very long voyage, indeed. Mom got out and rang the bell and a Hispanic man appeared a moment later. He opened the gate and waved us through. We made our way up the steep driveway and came to a gravel parking lot that was overflowing with shiny new cars.

Excerpted from “Jokes My Father Never Taught Me” by Rain Pryor. Copyright 2006 Rain Pryor. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced without written permission from