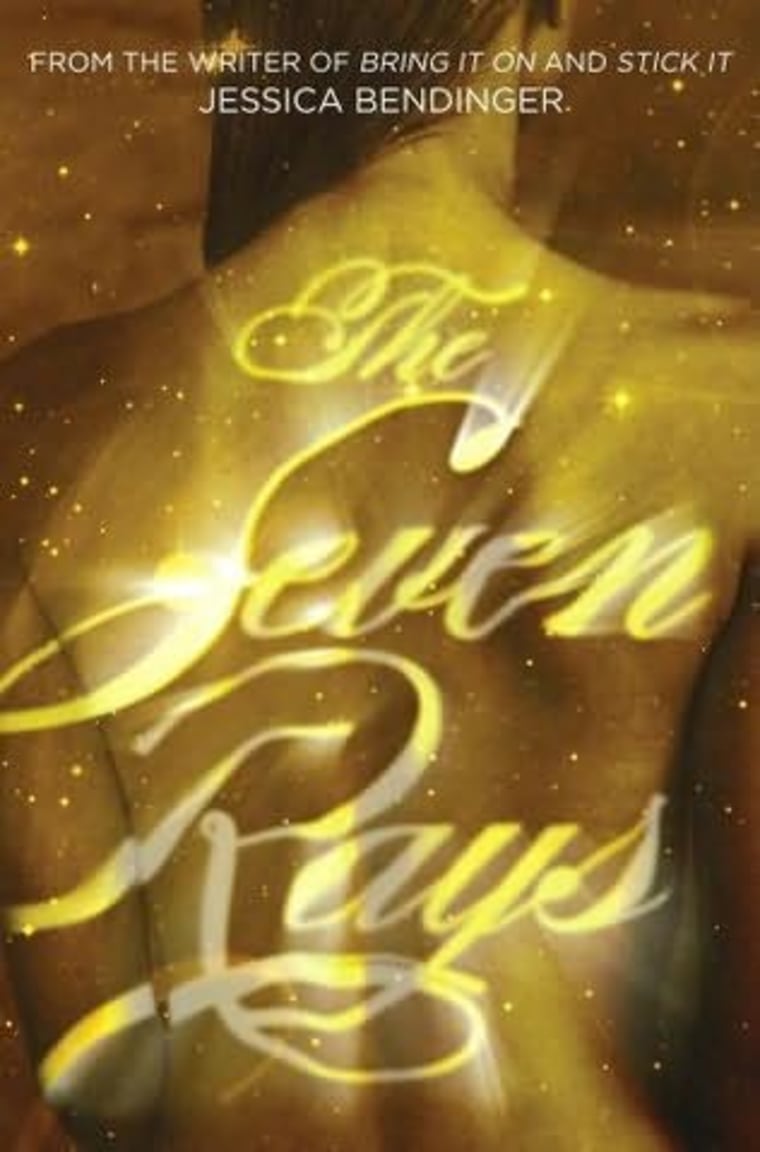

Lusting for a tale of that blends mystery with paranormal romance for you or the young adult in your life? The new book by author Jessica Bendinger — who penned the screenplay for the 2000 cheerleading film “Bring It On” — does just that. Here is an excerpt from chapter one.

Chapter 1

There are some things you can’t unsee. I don’t know when I started seeing things. I don’t know exactly when the little flickers started popping up, demanding my attention, mucking up my vision. I really don’t remember. Which is annoying, because you think you’d remember the first time your life was about to change irrevocably. But you don’t. When your personal cosmos explodes, you don’t remember precisely when the match first strikes the tinder. Or when the wick on the TNT gets lit. Me? I just remember pink dots. Stupid pink dots.

The only dots I’d seen previously were dotted lines, where I signed my name: Elizabeth Ray Michaels. Beth to those who knew me. Elizabeth to those who didn’t. I’m the only child of divorced parents, who neither speak to each other nor interact. This is a fact my overprotective, hardworking mother assured me was better than dodging my father’s fists and his screaming. It is also a fact I’ve learned not to question. In my seventeen years I’ve mastered one thing: the art of staying out of trouble, and a knack for insanely good grades. That’s two things. Two things that were about to change faster than a fourteen-year old boy’s voice. And a hundred times more awkwardly. But I’m getting ahead of myself.

I don’t remember if my eye-flashes first started when my mom blew a gasket over the fact that I didn’t ever cut or style my long hair. Don’t get me wrong: I brushed it and loved it. I had been growing it since I was seven. It was dirty blond, long and shiny, and the only thing I appreciated about my looks. Ever since reading that guys preferred long hair, I’d been growing mine. Superficial and shallow, I know, I know, but my hair was like my beauty raft: I clung on to it for dear life. Once Mom had tried to trick me into cutting it by giving me a certificate to a salon in Chicago. When I used it toward a mani-pedi? She ragged on me, and there was a red flashing dot. Like a flashing red smoke-alarm light that didn’t stop for several seconds. On her head.

The second visual flare was when my bestie Shirl wouldn’t admit she’d lost my favorite bag. She’d borrowed it. And failed to return it. Period. Okay. So, second to my hair? I loved my stuff. I didn’t have a lot of it, but what I did have, I adored. My old stuffed animals, my clothes, my books, my shoes, my bags. We couldn’t afford much, so I treasured everything and took good care of it. I guess I took “pride of ownership” a little too seriously at times, because I began naming things. Betty was the name of my favorite bag. So, when Shirl lost Betty and wouldn’t admit it? This blast of dots went off. “You treat your stuff like it’s alive, Beth.” She was railing on me like she always did when she’d messed up. “Who names their stuff? You’d think they were pets the way you dote on them; it’s ridic. And who do you think you are? Are you really accusing me of lying about something I could totes incredibly easily replace, anyway?” My things were like my pets. Betty was my fave and she was gone. And I was pretty sure Shirl was lying about it.

But that was all eclipsed by the fact that Shirl was covered in pink dots: tiny dots, pancake-sized dots, quarter-sized dots, nickel-sized dots, penny-sized and micro-sized dots. She was covered in all sizes and varieties of translucent, Pepto-Bismol pink dots. I was blinking so much at her she asked, “Are you developing eyelash Tourette’s, or what?” Then the dot-o-vision got all fuzzy and stopped. Sadly, eyelash Tourette’s was not to be the diagnosis. Or the live-agnosis.

Weird crap began popping in, out, and around people in my field of vision every day for weeks. I was terrified to tell my mother (who had a tendency to become hysterique about anything and everything), so I kept my mouth shut. I was tripping. Tuh-ripping. Although I knew there had to be a logical explanation for what was happening, I probably wasn’t going to discover it in my crappy high school’s version of AP Chem. Which wasn’t actually a class at my school, but (drumroll, please) ... a college-level course at the fabulously craptastic local community college! In fabulously craptastic New Glen, Illinois! Having sailed through high school with a 4.1 GPA, I finished junior year as a senior. The faculty decided my time was better spent off campus in college level classes than repeating classes I’d already straight A-ced. I’d be spending most of what would have been my last year in high school as an exotic export: a New Glen High School senior dominating the academic scene at NGCC (otherwise known as No Good Criminal College). By the way, there is no one less popular than a high-school kid in a college class crammed with college-aged underachievers. I was an interloper doing something my classmates had never dreamed of: graduating early.

It was the only thing I’d ever done early. I’d developed late, shot up late, and shot out late. Shirl and I were the last girls in high school to have chests that weren’t concave. We were never the cutest girls or the hottest girls or the most popular girls, the weirdest girls or the most annoying girls. You’d have to matter to someone, somewhere, to be any of those things. And we didn’t matter. To anyone, anywhere. Not when we met at New Glen Elementary, not at New Glen Middle School, and not at New Glen High. We were pretty much invisible.

In private, Shirl was a drama queen, constantly battling the nonexistent five pounds she had to lose, or complaining about her bad skin that was perfectly clear. She did it to combat her biggest fear, which she vocalized regularly: “We are becoming snore pie with yawn sauce, Beth! C’mon, let’s do something spontaneous and unforgettable!” Which usually involved the exciting rush of mainlining coffee at the local mall.

Shirl’s hobby was the cool kids. She pined for invitations to their parties, shopped where they shopped, knew where they hung out and where they worked. She studied them like they were constellations in a telescope: She understood what they were and how they behaved and could forecast their movements better than an astronomer. The difference between me and Shirl was simple: She wanted to be a part of their solar system. I wanted to get the hell out of that universe. And into university.

There was, however, one particular planet that Shirl revolved around: Ryan McAllister. Ryan Mac was the younger half of the lethally gorgeous, perpetually delinquent Mac Brothers. Stunning and troubled, athletic and not so bright, Ryan and his older brother, Richie McAllister, were legends around New Glen. They had dreamy hair, dreamy eyes, and the kind of sad family story that let them get away with anything. I didn’t know the details, but Shirl swore their father had abandoned the family under some kind of mob death threat involving guns and gambling debt. Their mother was in and out of rehab, and the boys were given the kind of free pass that is handed out to heart-stopping hotties with tragic life stories.

And how Ryan worked it! Ryan McAllister was the sworn nemesis of promise rings anywhere in a hundred-mile radius. Reputed to have deflowered bouquets of virgins, Ryan was legend. Arrested at fourteen, illegally driving an old motorcycle at fifteen, all-state in soccer and basketball by sixteen, Ryan Mac was drunk with power by seventeen. By his senior year Ryan had plucked more local buds than the horticulture industry. This naughty fact was how Ryan McAllister got his very naughty nickname: the Hymenator. His conquests were legendary, and were usually followed by the unfortunate and very public dangling of an unwrapped condom on the victim’s locker. Needless to say, Shirl would’ve willingly offered her rose to him without hesitation.

“I’m feeling thorny” was her whispered giggle every time we’d cross Ryan’s path.

“Hey, Charlene.” Ryan always got Shirl’s name wrong, and this didn’t deter her.

“A rose by any other name would still smell as sweet?” I squeaked out, trying to protect her fragile ego.

“He knows I exist. I’m making progress.” She was so gleeful about it. It was as if he’d just asked her out.

“Please don’t lose your V to Ryan McAllister,” I’d beg, rolling my eyes out of worry more than anything.

“He’d have to find it first,” she’d laugh. “Unless I lost it already. Do you think my virginity is in the lost and found box in Principal Tony’s office? I haven’t seen it in a while....” She’d joke about her total lack of sexual experience. But despite Shirl’s self-deprecating humor, I worried about the truth: She’d do anything for Ryan McAllister.

I reluctantly indulged her fixation by hanging out with her at the Bordens Books at Glen Valley Mall. Ryan worked part-time at the sporting goods store next door, and I could at least study and drink coffee while Shirl obsessed and memorized Ryan’s flight pattern.

There wasn’t one cool kid who Shirl didn’t know something about. Grenada Cavallo — the style icon of New Glen — never wore the same thing twice, and her luxury Vuitton bags were way beyond what most kids could afford. Shirl would speculate relentlessly about their origin. “Do you think Grenada is a master shoplifter or master Web-shopper and deal-finder?”

“I no know,” was my constant refrain. “They are your specialty, not mine.” I needed to nail my physics test, and she was not letting me master Newtonian mechanics. Shirl was sucking down her fifth coffee. “She says it’s a wealthy aunt who works at Bergdorf ’s in New York.”

“I didn’t realize the wealthy worked in retail.”

“I know, right? Lucky her.” Shirl was buzzing. “Did you see Jake’s new tattoo” — she knew I hadn’t — “on his lower back?”

“He got a tramp stamp?” I asked, incredulous. “How tacky and how tragic!” I detested tattoos. “Why not just wear a sign that says, ‘Please think I’m cool. I’m begging you!’ How’d you see Jake’s lower back, anyway?”

“He took off his shirt in PE.”

“Did the angels sing?” Shirl liked Jake. And by that, I mean Shirl liked all boys.

“Don’t mock me. You’re missing a lot, you know.” Shirl said it in a resentful voice, like I’d abandoned her and made a horrible mistake by investing in my future. “And now that you’re gone, he’s probably going to be valedictorian.” She was trying to rile me up, and I wasn’t biting. “I have to take as many college classes as possible. I can apply them as credits next year and save money. Gimme a break.”

It took a second to process what Shirl had said. “And since when is Jake Gorman smart?”

“His grades turned around after he was diagnosed with ADHD. They put him on Adderall, and he’s like an academic rock star now.” She was sucking on a straw, flattening the end and picking something out of her teeth with it. “You are so out of it! You can always make up college credits. But you will never make up lost time in high school. Jenny Yedgar is gaining weight. None of her clothes fit, and I have to sit behind her triple muffin top every day in Trig. There’s some super compelling drama unfurling. Especially if you find back fat riveting.”

“You are the most compassionate person on the planet.” I laughed.

“Jenny Yedgar is a bitch. And the weight has only made her meaner. She’s gone, like, all mad cow.” I had to get some studying done, so I pulled out the big guns. “Was that Ryan?”

’Twas a lie. But predictably, Shirl was out of her chair in his phantom direction at light speed. I took a deep breath to focus. I loved Shirl, but sometimes being friends with her was one-sided. In her favor.

As she ran toward her Ryan-stalking ground, little blobs of squiggles were streaming behind her, blurring like runny ink. Mine eyes are filled with eye mines! I said to myself as I tried rubbing them away. It didn’t work. The act of blinking was becoming dangerous, setting off explosions without warning. I snuck home early and climbed into bed.

The next day at No Good Criminal College, the eyebomb really dropped. At 11:33 a.m. in Chemistry, I thought my eyeballs were playing tricks, for sure. Because Richie Mac was smiling at me. Richard McAllister. The Richie Mac. Brother of Ryan. In all his nineteenly glory. Eyes of an angel. Body of a god. Smile of death. He waved at me and I looked around. Nobody moved. I looked back. He waved again. At me. He shook his head as if to say, Aren’tcha gonna wave back? As I was about to catch my breath and wave, some weirdness said hello. I mean, it’s not weird at all if the sight of dots animating before your very eyes is something you see every day. This time, the dots did something. They became giant fibers. Giant fibers braiding as they moved toward me. If the sight of three imaginary strands of nonexistent thread interlacing in the air is normal, forgive me. They didn’t cover that in my SAT prep course. Fortunately, my unexpected encounter with Beauty and the Braid got all fuzzy and blurry and disappeared in an instant.

“I think the word you’re looking for is ‘hello’?” Richie said.

“Uh, hi-llo, I mean, hello,” I blurted out as my cell began vibrating. My hello to His Royal Mackness was interrupted by a text. From my mom. DINNER 7:30. CHICKEN? It’s like she knew I was lusting after a boy who was completely inappropriate for me in every way, so she was busting my nonexistent flow. I resisted the urge to tell her to stop ruining my first taste of human eye candy when Richie spoke.

“It’s rude to take a text message in the middle of a conversation.. . .” He grinned. Shirl would’ve died. He was so beautiful I lost the power of speech.

“Sorry — my mom —” And that phantom braid, I thought.

“Is she as pretty as you are?” Richie said, without a hint of irony in his voice.

My blood pressure reversed direction, pausing briefly in my throat before flooding my cheeks and ears with heat. I don’t know, do your teeth actually sparkle? was my unspoken reply. I knew he wanted something, and I couldn’t risk speaking with all the blushing taking place on my face.

“I was wondering if maybe you might wanna possibly join our study group? It’s usually after class.” I noticed two college girls loitering nearby. They seemed less than thrilled with the prospect of me joining their band. “I’m Richie.” Even his voice was beautiful. How was that possible? I couldn’t speak for a second, and he beat me to it.

“Do you want me to guess your name? I enjoy games,” he joked.

“I’m Beth,” I finally squeaked out.

“Hey, Beth” — he pointed his enormous hand at the duo, and I wondered how he could pick his nose with fingers that large — “that’s Elena and . . . ?”

“It’s Marin, Richie. My name is Marin,” the girl who was not Elena practically spat. Richie looked at me like, Sorry about her. He added a shrug that said, How can I be expected to memorize names? I’m way too yummy for that.

I pointed to my phone. “My mom is expecting me.”

“I hope we’ll see you after the next class, then?” He must’ve been six foot four, and he leaned on my table for emphasis, twinkling his freakishly long lashes at me. I felt him towering over me, pausing before saying, “Beth?” My legs went numb. I could’ve wet my pants and never felt a thing, my body was that paralyzed by his appeal. I wasn’t hypnotized. I wasn’t magnetized. I’d been Mac-netized. I barely mustered a nod as he walked away. There I was. In Richie Mac’s Chemistry 101 study group. As my Mac-nosis wore off, I nervously slapped myself on the leg for being susceptible to his infamous charms. Maybe Shirl wasn’t crazy after all.

Before heading home, I had to pick something up at my future alma mater, New Glen High School. The sign outside read the ride of Illinois, the p in front of ride stolen long ago and never replaced. I texted Shirl to meet me in our fave spot: the girls’ bathroom near the teachers’ lounge. Other kids hated it because of its location. We loved it because it was always empty.

“What do you mean Richie Mac asked you to be in his study group?” I shouldn’t have told her. She had that tone friends get when they are jealous, and I hadn’t thought this through.

“Um, he says hello and that Ryan wants to marry you. I accepted on your behalf. I hope that’s okay,” I joked to ease the jealousy whammies coming my way. “You’ll be honeymooning in Cabo.”

“As long as the family doesn’t mind if I don’t wear white at the wedding. I’m planning on having a lot of sex before my wedding night, FYI.” Shirl was joking. This was a good sign.

We’d each had our share of odd make-outs and exploratory sessions over the years, but we were both virgins. This drove Shirl crazy. “I’m just going to sell my virginity on eBay. It’s such a curse. How much do you think I can get for it?”

“On the free market?”

“EBay is not a free market. You have to put down ten percent of your reserve price, so we really need to think this through. I’m thinking a million dollars.” I spit out my latte.

“We could totally get a cool mill for your trampoline.” The word trampoline was our synonym for the revoltingly unsexy word “hymen.” I mean, a word that sounds like “Hi, men!” seemed like a funny thing to call the membrane that separates virginity from sexual experience with actual men. Don’t get me wrong, I loved men and I loved my hymen, but we preferred “trampoline.”

Whenever either of us said it, that was our cue to do a lame sing-along dance we’d made up in seventh grade. We’d cover our crotches with one hand, point our fingers sternly with the other, and chant, “Cross this line and you’re a tramp! So do it while you’re off at camp!” Then we’d shake our butts and marvel at how stupid we were.

“How did we start calling hymens ‘trampolines’ anyway?”

“I think you’d heard some story about a gymnast busting hers doing tumbling —”

“Oh yeah, and how trampoline starts with the word ‘tramp’ and is a giant elastic thing everyone always wants to bounce on —”

“But no one wants it to break —”

“— without protection!” we’d say in unison. “Would anyone get that but us?” I asked.

“Of course not. No one’s as cool as us. Except the Mac Brothers,” Shirl cooed. “So what are we wearing to our double wedding?”

It was time to jet, and so I grabbed my stuff. “We really need to see the world, Shirl. There’s a sea of guys beyond Ryan McAllister.”

“We’ll see the world on our double honeymoon. We’ll wear matching outfits.” We low-fived a good-bye, and I had a weird feeling she wasn’t entirely kidding.

The school had called that morning and said I had a package waiting in the main office. When I got there, I was promptly lectured by Mrs. Dakolias, the school secretary. The moment she started speaking, her body grew something around it. I blinked. Out of thin air these gross knotted braids sprouted around her in every direction. Like I was hallucinating.

“We’re not a post office for students. We’re not supposed to accept your mail,” she chastised, as she presented me with a trashed FedEx envelope. The braids evaporated into nothingness before my eyes.

“They had to send it twice,” she whined. “The first time they spelled your name wrong. We couldn’t even pronounce it, let alone think it was you.” The original addressee’s name had been crossed out and replaced with the following: ELIAZABETH RAY MICHAELS, C/O NEW GLEN HIGH SCHOOL. I squinted at the newer Sharpie lettering, trying to decipher what name was underneath.

“What was the other name?” I asked, genuinely curious.“I don’t remember. It was some odd typo. We didn’t sign for it the first time — there was no name like that in the roster. We sent it back.” For someone who obviously disliked kids, Mrs. Dakolias had picked a strange job.

I nodded while staring at the envelope, pondering the return address. It was from a company called 7RI, with an address on Fifth Avenue in New York City. I didn’t know anyone in NewYork City. I didn’t even know anyone who knew anyone in New York City. It suddenly felt kind of glamorous to be getting a FedEx from the Big Apple. I hoped it was scholarship money. Please, God, let it be enough for Columbia, I said to myself, ’cause you know Mom can’t afford it.

I didn’t want to open the letter in front of anyone. “It’s probably some scholarship information, or something. I’m sorry for any inconvenience, Mrs. D. Thank you for your help.”

“Don’t let it happen again,” she grumped before returning to her filing.

“Beth?” It was Principal Tony, leaning out of his office and motioning for me to step inside. He was stuck in the seventies and was the kind of guy who you called Principal Tony. He broke up fights, and students liked him because he wasn’t a total dick.

I really wanted to open my package, and I was getting impatient. He extended some paperwork my way.

“I called NGCC. I need some signatures on these,” he lectured,“or you can’t graduate early, Beth.” I snatched the papers. Graduation — early or on time — could wait. I couldn’t wait to open my package.

I headed to the restroom, entering the big handicapped stall. I hung up my bag, put a thick layer of paper toilet seat covers on the lid, and sat down. I couldn’t take my eyes off that Sharpie lettering. There was an energy coming off the envelope that gave me a big feeling. Not the creeps or anything, but just like an anxious feeling when you are not expecting mail from a company called 7RI and they’ve sent something to your school. It was disconcerting and kind of thrilling. I prayed for big bucks. Big Educational Bucks, por favor!

I pulled open the tab. I closed my eyes and took a deep breath. Inside was another envelope. Gold and small, like an invitation. On the front of the envelope, in very careful lettering, was the name Aleph Beth Ray. Odd typo indeed. It didn’t even look remotely like my name, and I started to doubt it was for me. I rechecked the packaging. That was my name on the outside, right?

I flipped it over and saw a beautiful, antiquated wax seal. I carefully peeled it back so I could do forensics later. I extracted this heavy piece of pulpy, old-fashioned paper from the envelope. The message was written in block lettering. Only eight words. Eight words that read YOU ARE MORE THAN YOU THINK YOU ARE. I flipped it over. That was it. Eight words, eight words that couldn’t possibly be for me.

Excerpted with permission from “The Seven Rays” by Jessica Bendinger (Simon & Schuster, 2009).