The recent rise in anti-Asian hate incidents, mostly against women, has rattled my senses. I now walk more quickly down the streets, looking over my shoulder. My heart hurts. I’ve tried to think of something I can do to feel less powerless, how I can make meaning out of the meaningless. So, I decided to turn to my own past and reach out to a boy (now a man) who was cruel to me for years, all because I am Asian.

I grew up in North Carolina and attended a perfectly fine public high school that was about 70 percent white and about 3 percent Asian. I excelled in advanced courses, which had the structure and support of good teachers. But I rode the bus to and from school most days, and there were no adults to call the shots. I was a small girl and the only Asian kid on the bus. Therefore, I was easy prey for the few mean kids who ruled the roost. They would call me a “chink b----,” tell me to cook them “white lice,” pull their eyes sideways at me and sidle up into my seat and shout “ching chong” at me. And none of the other kids intervened. Not once.

The most frequent offenders were two boys whose faces and names I’ll never forget. They were each almost twice my size. I got so tired of choking back tears. The memory of their twinkle-eyed sneers still haunts me.

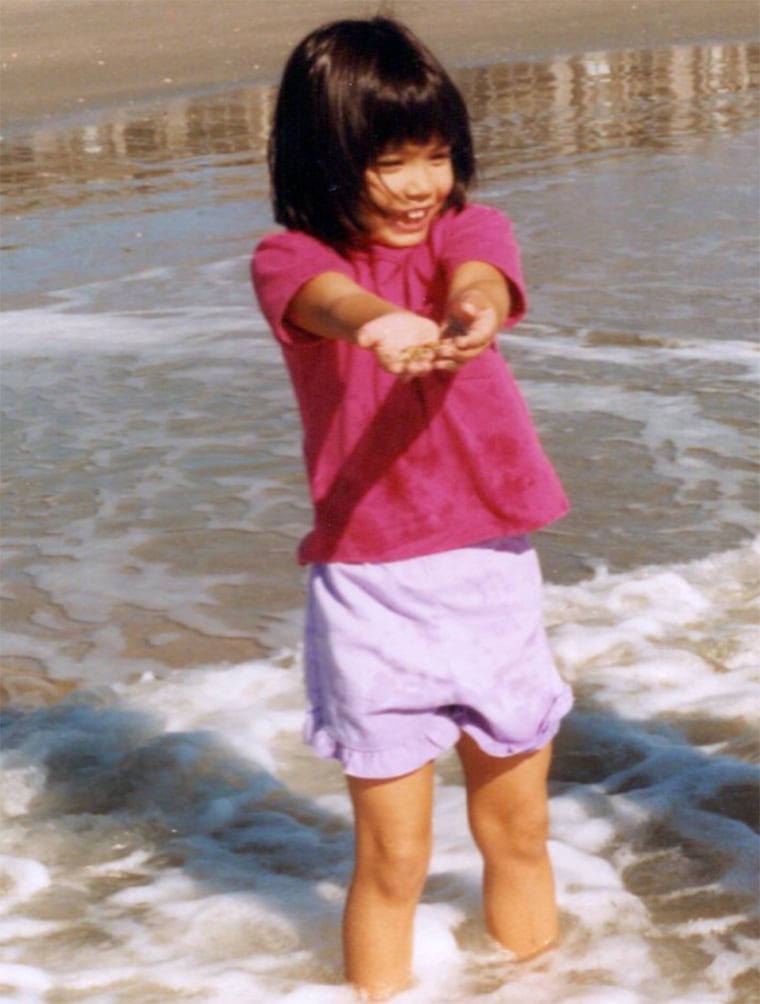

My dad is an immigrant from Malaysia, from a province on Borneo called Sawarak. His family is ethnically Chinese; they fled China in the early 1900s to escape religious persecution. He grew up in a longhouse, up on stilts to survive the frequent rainforest floods. He learned English in a nearby village, which he reached by crossing the river in a canoe each morning.

He immigrated alone to the U.S. to attend college at Ohio Wesleyan. He met a fiery blond freshman named Ann, and they hit it off. They married several years later, despite protestations from her family that she had chosen a “damn foreigner.” A few years later, they moved to Durham, North Carolina, and had me, the first of three daughters.

That boy on the bus didn’t hate me because I was Asian. He was a mean teenager, and I was an easy target because I was Asian. That’s what society allowed to happen, so that’s what he did.

After college, I struck out for New York City. But being a professional 500 miles north didn’t spare me from racial comments. But the murky nature of those comments have often left me wondering if I’m crazy to be offended. When strangers in the street have yelled “Me love you long time,” that’s obviously bad. But what about when loved ones call me “exotic,” thinking it’s a compliment? Or the hundreds of times someone has asked, “What are you?” Or when a past manager once told me I was a “beautiful China doll” when I wore a red dress to the office?

Ten weeks after the insurrection at the U.S. Capitol, which was perpetrated mostly by white men, Sen. Ron Johnson of Wisconsin said that he “never felt threatened” by the invaders, but he might have been afraid if they had been Black Lives Matter or Antifa protesters. The racial implications were obvious. In another interview that day, he said that the armed insurrection “didn’t seem like an armed insurrection to me.” That word “seem.” His bias, conscious or not, was so strong that he denied undeniable facts.

On Tuesday’s “Morning Joe,” Daily Beast columnist Matt Lewis suggested that Sen. Johnson, in his heart, “does not believe he is a racist.” He called the comments the best case study for unconscious, subliminal racism. That got me thinking about the boys on the bus. Were they really racist, or were they just angry, mean kids, grasping at whatever insult felt easiest?

I took to the Twittersphere.

“I wonder if the kids who pulled their eyes at me and mercilessly yelled "ching chong" at me on the bus even remember doing it,” I wrote. “The two worst offenders are both parents now. I wonder what they teach their children.”

A few minutes after I posted, I decided “wonder” wasn’t enough. I would go to the source and ask one of those school bus tormentors if he remembered being unkind to me. I opened up Facebook Messenger, gulped hard, and hit send. I thought he would probably say nothing, and I prepared myself for the possibility that he would lash out at me or gaslight me with denials. But my driving force was curiosity, not vengeance.

After 10 chest-pounding minutes of seeing the three dots bubble in his corner, I received one of the loveliest, most vulnerable apologies I’ve ever gotten. And my suspicions were founded: He didn’t specifically remember being cruel to me. But he didn’t shy away from taking responsibility. “I’m really sorry for making you feel that way. I was def an a—hole kid! Not making excuses at all because I feel horrible knowing I made you feel that way!” He added, “I acted out thru much of my younger life because honestly I wasn’t happy and peaceful with myself … There are a lot of things in life I wish I could take back and this is definitely one.”

I sat on my couch and cried. My heart healed more in an instant that I thought possible. He and I went on to chat for more than 30 minutes and agreed we wish we could hug and introduce our children to each other someday.

Matt Lewis nailed it. That boy on the bus didn’t hate me because I was Asian. He was a mean teenager, and I was an easy target because I was Asian. That’s what society allowed to happen, so that’s what he did.

But what can we do to get at the root, to stop the systemic bias before it hardens to racism and metastasizes into violence?

On social media, many well-meaning people this week have repeated a common refrain: We all can and should do better. Solidarity is an important first step, and it helps those who have felt alone and attacked. But what can we do to get at the root, to stop the systemic bias before it hardens to racism and metastasizes into violence?

What moved me most on the Twitter thread were the handful of people who took the opportunity to confess being racially mean to other kids growing up. They ache about it. They aren’t racist, they say, and they know better now. And I’m inclined to believe people who are willing to expose themselves like that.

So I’m curious: Do you want to do better? Is there an acquaintance or friend who might be open to having a frank but open-hearted chat about race? Consider taking an awkward social plunge yourself. As I’ve learned, it might be well worth it.

Cat Rakowski is an Emmy-winning journalist and a booking producer for MSNBC's “Morning Joe” and “Way Too Early with Kasie Hunt." She lives in Queens with her son, Lincoln. Follow her @catrakowski.

This article originally appeared on NBCNews.com.

Related: