I moved to America from Cameroon when I was 6 years old as the daughter of a diplomat and a global activist. When we got to the United States, we ate a lot. My mother told me, “If you want to know America, eat.” And so we did. She took us to eat all over New York and even the world. I am so fortunate to have had pizza in Italy’s Piazza Di Spagna and also Brooklyn, New York. She was keen on me not feeling other from African-American culture so we ate soul food a lot, too.

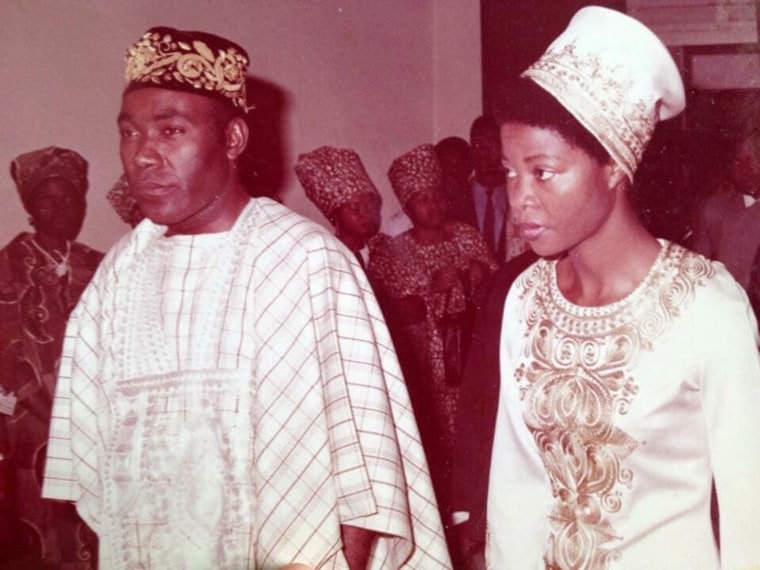

My father was the new ambassador to the United Nations from Cameroon. He said that he learned the most about people from meeting them and listening to their stories, especially over a good meal.

When he had time and was home from missions, my father and I watched movies and TV shows together. Once I asked him what he did if someone said something he disagreed with while he was working. He told me that before speaking, he plays a short movie of who the person is in his mind, and then addresses that person with respect. He said to me, “What if I told you that I’m about to walk out of this room and bring in to meet you a person who has escaped war, been raped and survived? What if, when I brought them in, they didn’t greet you with a smile? Then you would know that it may not be about you, but their experience, that wrinkles their tone.”

I followed in my parents’ footsteps when I grew older and became an activist. I worked mostly on the HIV/AIDS crisis. Influenced by my father’s love of movies, I used film to educate people. I started a film festival at the United Nations. But while I was equipped for public relations, I made a muck of private ones. I was too sensitive. I didn’t have thick skin. The stories of death and injustice I was exposed to were hard on me.

I began to drink a bottle of wine each night to fall asleep. I stopped eating properly and began binging — at one point, I was eating three or four cheeseburgers in a single sitting. Then six or seven cheeseburgers became normal. I was out of control and in terrible spiritual and physical condition. I was depressed. I knew it had to stop. One day I began to write a list of what I wanted: family, children, good health. My desires poured out and just the thought of these things made me happy.

At one point, I was eating three or four cheeseburgers in a single sitting. Then six or seven cheeseburgers became normal.

Change started that afternoon. I went to a therapy session and then headed for a drive in Palisades Park, New Jersey, a town with a mostly Asian population, many of them Korean Americans. I pulled into a small mall that housed many Korean businesses. I was looking for a shop that sold healing items like jade stone beds, which my mother and I had visited before. The shop had shut down, but as I was walking down the hallway to leave the mall, a Korean bakery worker offered me a bread sample, which I accepted. The delicious cream swam across my face and dripped down my chin. Suddenly, I heard a voice: "You are too fat, don't eat this bread.” I turned to find an elderly Korean woman, standing in front of a grocery store, hurling her words at me with dart-like precision. Then my father’s advice returned to me: Press play before a response. I envisioned her story, then responded.

"Well, if you think I am fat, what should I eat then?" I asked her. She softened, not much, but perhaps she was considering my respect.

“Korean food,” she said, ending the word food with a soft “uh” sound. Her words rang in my soul. Food had been my guide to Americana.

“Can you please show me?” I asked. “Can you help me?”

We walked into a grocery store named Han Ah Reum (now known as H Mart, the largest Asian grocer in the U.S.) that was right across from the bakery. I left with more than an armful of groceries: raw greens, pre-made Korean side dishes called banchan and kimchi.

At home, I opened a jar of kimchi and as the white plastic top slipped off, here came the smell. Heaven. The most awakening, delicious smell. I could almost taste all the ingredients already. I ran to my kitchen drawer, searching for chopsticks from a food delivery in my drawer full of menus and random plastic forks. I began to eat the kimchi and felt what it was like to eat electric, alive food for the first time.

I felt what it was like to eat electric, alive food for the first time.

I met with the Korean elder, who told me to call her halmoni (the Korean word for grandmother), many times after that day. My taste for kimchi grew and I began to eat it with everything. It made me feel full, and it satisfied my taste buds. I began to lose weight. In a year, I was 110 pounds lighter. Korean cuisine became a regular part of my diet and I was healthier. I was eating such a large amount of fermented, raw and steamed vegetables that I even became vegan, with the exception of kimchi. (Traditional kimchi is not vegan because it usually includes fish sauce and/or shrimp paste.)

The way the grandmother showed me love is now part of my movie — the sequence of scenes that I like to imagine one sees when they meet me. This exploration of other cultures and cuisines and the magic that can come of it is why I love America. I am now an American woman and the mother of three biracial Cameroonian Korean American children.

I hope my story inspires you to embrace another culture, whether it is Korean, Jamaican, Ethiopian, Italian, Indian or something else. Reach across the table for a serving of our magnificent American dream, for it may lead to your transformation, too.

Read more about Yoon’s story in her new book, “The Korean,” out Nov. 17.