When you've proven the existence of a salty lake on Mars, what do you do for an encore? NASA's newly supercharged rovers may be racing toward an answer. “I think some of the best stuff may still be ahead," the program's chief scientist said Tuesday.

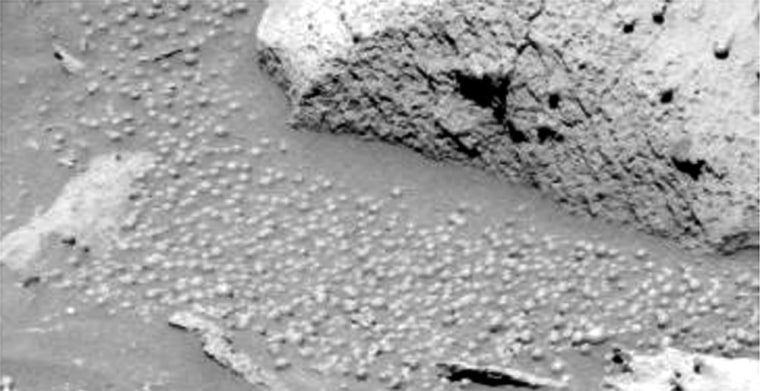

Steven Squyres spoke to MSNBC.com just after his team had seen the first images of Fram Crater, the first crater the Opportunity rover has looked at it in detail since it left Eagle Crater, its interplanetary hole-in-one landing spot on Mars. It was Eagle Crater's perfectly-preserved sediments that yielded the evidence of a Martian shore.

Fram Crater, on the other hand, is not so neat.

“Fram is really busted up,” Squyres said excitedly. “It’s really scrambled, disrupted stuff, with ejecta blocks lying around.” He speculated that whatever object had hit the Martian surface to form Fram Crater had been going at a much higher speed than the one that hit to form Eagle Crater.

Squyres and his team are also excited by the rovers' newly pumped-up speed. Just two months ago, it was cause for celebration when the Spirit rover traveled nearly 70 feet, or 21 meters, in a day -- shattering by more than three times the record set by the Pathfinder mission in 1997. With the new navigation software installed, Opportunity recently performed a one-day drive of 155 yards, or 142 meters.

“Release-9 is fantastic,” Squyres exulted; “We are loving it, especially the mobility.”

This new speed is what is enabling the rovers to reach exciting new regions to explore.

Mini-tornadoes and a long trek for Spirit

Spirit has just arrived at a crater dubbed “Missoula.” While not as rocky as the Bonneville Crater that Spirit explored earlier, it’s interesting enough to keep the rover busy for a few days.

Along with taking images of the rocks thrown out by this eons-old meteorite impact, Spirit's cameras are scanning the skies to do “dust devil fishing": seeking time-lapse images of Martian mini-tornadoes. When captured by cameras on probes orbiting Mars, these mini-tornadoes show up as tall, thin white clouds, casting a shadow and leaving a dark trace on the ground as they move. In Spirit’s cameras, nothing has shown up so far but the odds are that persistence will pay off.

In a few days, Spirit will head for the hills –- the “Columbia Hills” that were named in honor of the shuttle crew lost last year. "We’ll proceed at a good purposeful pace so as to arrive when we still have plenty of rover [lifetime] left,” Squyres said.

As the hills grow closer, the science team will look for specific features. “First is bedrock outcrops,” Squyres said, adding that photos from space show that a lot of material was eroded out of the area by massive floods. The hills probably are remnants of that erosion and could show distinctive signs of the process, and what the region looked like before the floods.

“We’ll be looking for any kinds of layering,” Squyres said, "and other than that, any things that look different – we’ll see what Mars gives us.”

There could be landslides, dead geysers, evaporite beds, towering cliffs showing cross-sections of a billion years of Martian geology, even cave mouths into the hills. Spirit will probably spend the rest of its life wandering these hills.

Opportunity hopes to dive deeper

Halfway around the planet, Opportunity is exploring the sand dunes of the Meridiani Plains. After the rover finishes with Fram Crater, it will head toward Endurance Crater, a trip of about a week.

“At Eagle Crater, we saw the upper 30-40 cm of the last chapter of what may be a long and pretty complicated book,” Squyres said. “It showed us the last dying gasps of a body of water –- shallow, salty, evaporating away.” But what about earlier chapters in this book?

“My hope is at Endurance we’ll see deeper down and find evidence of sedimentation in deep water,” he continued. The rover’s instruments should be able to determine this by measuring less salt and more mud in the layers.

Clues from images of the crater made by orbiting spacecraft have led Squyres and his team to suspect that at Endurance, layers are exposed not just at the top, but “farther down the walls” of the crater as well.

Once Opportunity sends back images from Endurance, the mission scientists will have some decisions to make. “We’ll make a very detailed model of the crater,” Squyres said, “and then we sit down and think real hard about what to do."

“It may be we can get in,” he said, "and it may be we can get in but can’t get out.” Even in that case, if the scientists decide that they can get access to the rest of the "book of Mars," they may take the plunge.

If Endurance doesn't mark the end for Opportunity, the rover may press on to other regions of interest. Squyres described "etched terrain" to the south where surface coloration suggests changing rock types.

“There are two ways to get deeper down,” he explained. “You can find a hole, or you can find rock layers where the surface is tilted slightly to form a very gently sloping surface.” On such structures -– and the "etched terrain" could be one -- the rover could reach lower and lower layers simply by moving downhill across the surface.

'Every last drop of science'

Scientists at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California, where the rovers are controlled, have made it clear that the vehicles could break down suddenly at any moment. The main threat is the severe thermal swings of the day-night temperature cycles. A critical power feed or computer chip could just snap, and the rover would be dead.

However, the prime limiting factor on vehicle lifetime was originally thought to be a gradual decay of electrical power generation from the solar arrays, as Martian dust built up on their surfaces. But while there has been "some degradation,” Squyres said, “it is flattening out.” One possibility, others have speculated, is that the rovers' bumpy progress is shaking some of the dust loose.

“We’re finding ways to streamline our operations to make this mission sustainable,” Squyres said, voicing a hope that the rovers could survive for a long, long time -- and not kill their ground control teams through overwork, either.

“Our job is to wring every last drop of science out of these rovers,” Squyres said. And with the new regions about to be explored, that science harvest will continue.