My cousin Kane Jungbluth-Murry is Black. Our family is white.

I was 4 years old when Kane was born. Race was never anything we discussed too deeply. He’s my cousin, a voice actor, a writer, a father of three, a fantastic maker of cocktails and a lot of other things. Yes, he’s also Black, but our annual visits on Christmas Eve in Arizona were usually reserved for talking about what we had been up to the past year, not how we could work to dismantle systemic racism in the United States.

The conversation changed on May 26 of this year, the day after Derek Chauvin put his knee on George Floyd’s neck for 7 minutes and 46 seconds, according to prosecutors.

For Kane, who spent most of his formative years living with his white side of the family (my side of the family), navigating the social media posts, the comments and the lack of solidarity from his own relatives has come as a “rude awakening.”

“I think I assumed for the longest time it was a given, pretty much across the board, that the people I loved would stand for human rights and civil rights,” Kane said. “I would see things in the news and on social media that sounded crazy and were racist and I thought, ‘Well it hasn’t happened to me and my family aren’t like that.’ But May 25, George Floyd, is what really did it.”

The ‘token Black kid’

Kane's father, my first cousin, was in high school when he announced he was expecting a child with his then girlfriend, who is Black.

“I am more prominently Black than white or anything else, but I was raised mostly by the white side of my family. I saw them more. I engaged with them more. I don’t really know if I recognized there was much of a difference when I was younger,” Kane said. “I think it was more as I got older and an early age of 8, 9 and I started to see the difference because I was pretty much the token Black kid at school.”

When Kane was in middle school, he moved to Temple, Texas, to live with his mother. While he was around more Black peers for the first time in his life, it’s also where he had the first brush with direct racism.

“When I was younger, I spoke in a way that was referred to as ‘Black.’ I was made fun of by one of the white kids at school and I literally had to go home, cry it out and think about it, because I did not know what that meant, what ‘talking Black’ was,” he said.

Kane didn’t ask his mother. Instead, he did his own research.

“I had a computer at home and some dial-up Internet and was able to figure out what that even meant, and was then able to look at the movies and TV and that is really what it was. I watch all these movies and the characters are this. I listen to this music and they speak this way and I just followed those ways of doing things,” he said. “After that small brush with racism and just the frustration, I started reading a thesaurus I had and started practicing how I enunciated my words so I could change the way I spoke. Over time, I started speaking very properly. And now it’s my career (as a voice actor), which is good, but it was all based off of being made fun of for sounding Black.”

Kane moved back to Arizona in high school and lived with our relatives. He and my sister, Nicolette, went to the same high school. They loved when people discovered they were related and seeing their reactions.

But looking back, he wasn't prepared by the adults in his life for the sad realities of racism. He never got “the talk” that many parents have with their Black sons and daughters, letting them know how to prepare for an encounter with a police officer and ensure they get home safely.

“Maybe that is what helped for me not to realize racism so suddenly. Everyone was kind of the same. Racism is definitely not embedded in a child’s brain out of birth,” he said. “I didn’t even realize I needed to have the talk with my own kids until everything kind of exploded back in May. That’s when I figured out I need to talk to my kids now, because that matters.”

Kane's daughter is 9 years old. His sons are 5 and 2 and a half.

“I want them to understand what could happen in the world to their dad or to them at some point. If it were to happen, I would hope to God it wouldn’t, but it’s just a possibility for us in this country,” he said.

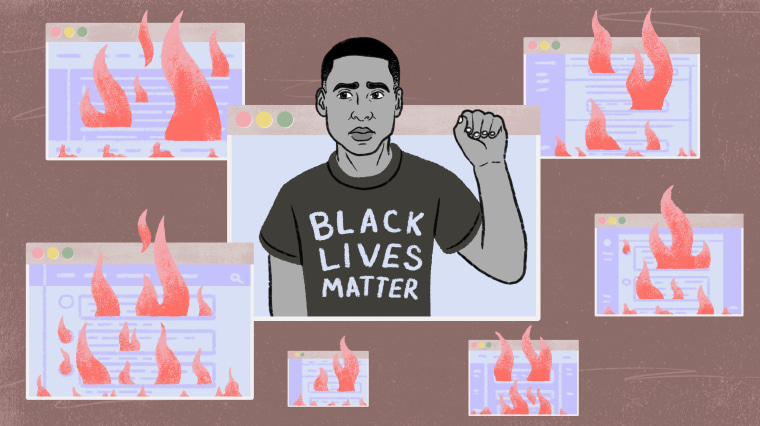

The family divide on social media

Kane is a valued and loved member of the family, but plenty of our white relatives aren’t trying to understand or acknowledge the scourge of systemic racism in the United States. And it’s deeply upsetting to him.

“With some of my family members it has been easy to talk about it and with others, it has been extremely difficult to the point where we are separated,” he said.

Kane uses his platform on social media to post videos and photos from Black Lives Matter events and other peaceful gatherings promoting human and civil rights. He also occasionally turns the camera on himself to share how he’s feeling. In one post, he opened up about how he wished more of his white family members would stand with him on the right side of history and acknowledge the systemic racism in this country and that Black lives matter.

Some of the comments in responses stung. He’s been told he should “be grateful” for everything they’ve done for him. Another comment suggested he become a police officer if he wants to enact true change and that he should stop complaining.

“All of the frustration, the anger, the actual true selves came out, whether it was good or bad, it came out. I was shocked a little bit because I didn’t understand it and I didn’t for months and months, up until now,” Kane said. “It was already embedded into that person that I love. They always felt that way. It wasn’t George Floyd and these protests that made them feel this opposite way from how I feel. It was already who they were.”

While he won't let the stark differences in opinion shake the love he has for his family, he is happy to make use of the unfriend and mute buttons as tools to save his mental health. Kane also said he's prioritizing being around friends and the few family members who understand why he supports Black Lives Matter.

“If it was me, if it was one of my kids, my partner, then what would you do? I asked that question and didn’t necessarily get a real answer from some relatives,” he said. “Just because it happened to someone you don’t know, doesn’t mean it can’t happen to someone you do know.”