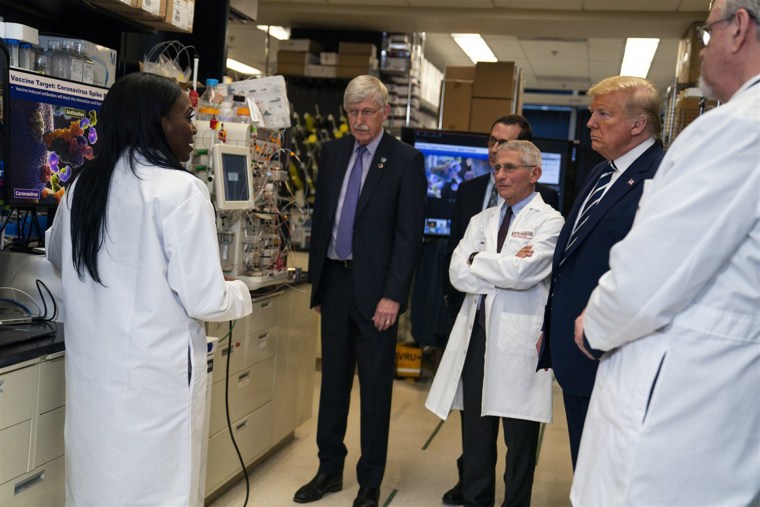

The day President Donald Trump went to the National Institutes of Health for an update on progress toward a vaccine for COVID-19, many of those who sat behind the presidential seal with him were white men well known in the worlds of science, medicine and, now, national anxiety control: vaccine and infectious disease specialists like Dr. Anthony Fauci, Dr. John Mascola, Dr. Barney Graham and the man who led the human genome project, Dr. Francis Collins, director of the NIH. Sitting next to Graham was Kizzmekia Corbett, an NIH research fellow.

In 2003, Fauci said at the event, NIH scientists managed to identify SARS and get a vaccine to stage-one clinical trials in 20 months. Now a team of scientists led by Corbett, 34, was poised to move to first-stage trials for a coronavirus vaccine — this time, in about two months.

That was March 3. Just 122 people had tested positive for the coronavirus in the U.S. Reporters stationed around the edges of the room asked the president about virus-related travel bans and his Super Tuesday predictions. No one asked Corbett — whom Collins had just described as a "wonderfully talented young scientist in our midst," as well as the only woman and black person at the table — a single thing.

Just 13 days later, Corbett's team began first-stage clinical trials of a COVID-19 vaccine, the first of its kind in the world and the fastest progress ever toward a possible vaccine for a novel pathogen. At least 40 distinct groups of researchers in China, Germany, the U.S. and other countries soon followed. But if Corbett's team is successful — meaning phase one, two and three clinical trials prove the team's work has produced a safe, working vaccine — something to prevent infection with the coronavirus could be ready for use in doctors' offices by early to mid-2021. COVID-19 could become a preventable disease.

"There was, and is, already a fair amount of pressure," Corbett said. "A lot of people are banking on us or feel that we have a product that could, at least, be part of the answer this world needs. And, well, whew, just saying that out loud is not easy."

"Not your average pocket-protector scientist"

There are other statements that Corbett expresses with ease, however. Take, for instance, when Graham met her 12 years ago, when she was an undergraduate doing summer work at the NIH's Vaccine Research Center, and asked her what she ultimately wanted to do with her life.

"She said, 'I want your job,'" Graham recalls. "From the very beginning, she was really pretty bold in her aspirations. And I, if I recall correctly, I was just glad to hear help was coming."

Full coverage of the coronavirus outbreak

Corbett was clear that her route included getting a doctorate and ideally working on rapid vaccine development — an aria to Graham's ears. Rapid vaccine development, particularly for novel pathogens with the potential to create pandemics but not big corporate profits, almost always requires singular focus and scientists willing to sacrifice.

Corbett stuck to the plan: majoring in biology and sociology at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County, and dividing her time between lab and field work on health outcomes in diverse communities. Corbett earned a doctorate from the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill in 2014.

Now she's a fellow at Graham's center leading the coronavirus vaccine development team.

"She's not your average pocket-protector scientist," said Andrew Ward, a professor at Scripps Research, an independent research and graduate education institution. Ward, who specializes in structure-based vaccine design and atomic-level modeling, is part of Corbett's team.

"There's pressure, constant pressure, in a situation like this where the speed at which we've gone to clinical trials is almost unprecedented," Ward said. "And I think there's a lot of realism on the team that this is a shot, maybe not even our best shot, but a good shot, given the pressing need. And Kizzy, to me, really epitomizes that. She's putting in long, long hours, doing critical, potentially world-altering work, at what is naturally a pretty high-pressure time in her career, in this incredibly focused way."

Ralph Baric, a professor in the departments of epidemiology, microbiology and immunology at the University of North Carolina, calls Corbett "a really quite outstanding, hard-working scientist."

"Fate has put her in a position to make a huge difference in human health, and it has made a good choice," said Baric, who has spent 35 years studying coronaviruses and evaluated Corbett's doctoral research on dengue fever. He is part of Corbett's vaccine development team conducting critical experiments.

"Corbett seemed drawn to dengue research for two reasons: the suffering the disease causes and the complexity making vaccine development challenging," Baric said. "In retrospect, it was solid preparation for COVID-19."

Corbett turned her attention to coronaviruses when she joined the NIH's Vaccine Research Center as a postdoctoral fellow in 2014.

"SARS and MERS, two coronaviruses, had already caused massive outbreaks," she said. "And these big, challenging questions remained, along with the fact that it was clear that it could happen again. It was looming out there and just a matter of time."

Working for Graham, Corbett was deep into her exploration of coronaviruses when COVID-19 emerged last year.

Corbett and members of her team had identified a particular "spike protein" in coronaviruses like COVID-19 that sticks out from the virus' surface. The claw-like shape permeates healthy human cells, infecting them. Building on decades of research by many scientists, the potential NIH vaccine uses a genetic code sequence known as messenger RNA, or mRNA, to prompt the body's immune system to react when the spike protein is detected, blocking the infection process.

On March 3, that's the science that Corbett explained to Trump during his NIH tour.

Fauci, Corbett and Graham donned lab coats and moved the president through a warren of working labs with whirring machines crunching data, displaying or analyzing 3D models of the virus and freezers with the capacity to store samples at minus-80 degrees.

Corbett declined to comment on the president's relationship with science. But that day at the NIH, she said, Trump listened and asked smart questions.

Three days later, Trump signed a bill authorizing an $8.3 billion emergency coronavirus response, which included at least $3 billion for development of testing, vaccine and treatment.

From loving Jesus to making jokes

Along with all that scientific devotion, Corbett remains connected to other parts of life, capable of talking about science anywhere from "the trap house to the White House," she said in an interview with Black Enterprise magazine. It is one of the many blogs, podcasts, social media platforms and various news outlets with largely black audiences that have devoted time to Corbett's scientific work and background.

In the days before strict social distancing measures took hold, Corbett told her Twitter followers that she got an "emergency weave" and had her eyebrows sculpted. She's since joked about having to put on a real shirt to hop on a work videoconference call.

Corbett is a scientist who loves Jesus, hates mercenary operations falsely claiming they have produced a coronavirus shield from household spices and worries about how seriously people — especially at churches on Easter — take social distancing recommendations.

In a rare moment of levity since clinical trials of her team's possible vaccine began, Corbett joked that rappers Young Jeezy and DaBaby will be asked to perform should she ever win a Nobel Prize.

"She's brilliant and doing this complicated work and yet, somehow, is also this person who manages to remember everybody's birthday," Ward said. "She's really great at bringing together groups of people with different skills and understanding the value and contributions of each of them in ways that really maximizes scientific impact."

'Critical thought is just how I roll'

Corbett was born in Hurdle Mills, North Carolina, a town of less than 4,000 people about 30 minutes south of the Virginia border. Everyone thinks their baby is special, especially their first baby, said her mother, Rhonda Brooks.

"Kizzie was always like a little detective," Brooks said. "My sweet little, opinionated detective."

Brooks also recalls when Corbett's third grade teacher, a black woman, told her and her husband, Corbett's stepfather, that they should do everything possible to make sure their daughter was put on the most demanding academic track — something the district rarely considered for black children. They should push, the teacher said.

Eventually, the family moved 20 minutes south to Hillsborough, where Brooks raised her math whiz daughter just like her six other birth, step and foster kids.

When it was time for college, Corbett had multiple offers, including from a college known as a Southern party school and another from the University of Maryland, Baltimore County, where she was accepted to the Meyerhoff Scholars Program and offered a full scholarship.

"It was like, do I go for the fun or do I go for the funds?" she said. "I chose Meyerhoff because of the money, the network and the program. Critical thought is just how I roll."

In terms of the coronavirus alone, Meyerhoff Scholars is also the program that produced Olubukola Abiona, a scientist preparing for graduate studies working under Corbett at the NIH's Vaccine Research Center; Jerome Adams, surgeon general of the United States and part of the White House's coronavirus task force; and Darian Cash, a senior scientist at Moderna, a biotech firm and part of the scientific group working with Corbett. All three are black.

"That is not and cannot be a coincidence," said Keith Harmon, director of the Meyerhoff Scholars program, who was one of Corbett's advisers in college. The program has helped to make the school the predominantly white institution producing the nation's largest number of African Americans who earn medical and doctoral degrees.

"When I think about Kizzy, I'm not at all surprised she's one of the scientists on the edge of a vaccine," Harmon said. "Not one bit. What I am reminded of is that there is such ability, untapped, unrecognized and un-nurtured among students, all our students, particularly among our underrepresented minority students. And if we accept that as normal, you really have to wonder what serious challenges we leave unsolved."

Long workdays and coping strategies

The work itself is exhilarating and hard. Right now, it also demands seven-day workweeks and getting three to four hours of sleep each night. Information is constantly arriving at all hours. Decisions need to be made. There are so many calls, emails and requests for data, for samples, for tests that measure how well the virus has been blocked that Corbett jokes she needs someone just to read her email.

Yet she manages it all — while also trying to digest side helpings of disrespect.

In meetings and emails or on conference calls at least a few times every day, Corbett said, some scientists around the world double-check her work or ideas with Graham or direct questions to him — even though Graham makes it consistently clear that Corbett is the scientific lead and the ultimate expert. Corbett said they thank Graham when she answers their questions or provides data, samples and tests.

On Twitter, someone recently suggested that she should "go back to McDonalds where she belongs."

Corbett has a few coping strategies. She has a boss who believes in her, so she's not afraid to ask questions, seek direction or try new approaches. She's so organized that she's known as "the spreadsheet queen" who plots out everything from clinical trials to her best friends' children's birthdays.

She tries to engage fully with the issue before her. Corbett makes time to check in with her three nieces and nephews almost every day. She leans on family and friends, especially her two grandmothers, for whom "Jesus is like a bff," she said. And she extracts confidence, scientific and social information from doing the work.

"At some point, you have to decide how much to care," Corbett said. "You understand that your work will have to be mighty so that it can do your speaking."