Most robots are so much more than a pretty face, but most humans don't see them that way. We make snap decisions about a robot's personality, friendliness and abilities — all from the way it looks, even if it's just a projection on a display screen, new research shows.

A new study, published in the Aug. 28 issue of PLOS ONE, adds to growing evidence that as robots become assistants and collaborators in all aspects of our lives, their appearance can deeply influence how well machines and humans interact.

The authors of the study recruited 30 volunteers, ages 18 and 38, to interact with three different robot avatars for the PeopleBot robot, which helped them take their blood pressure.

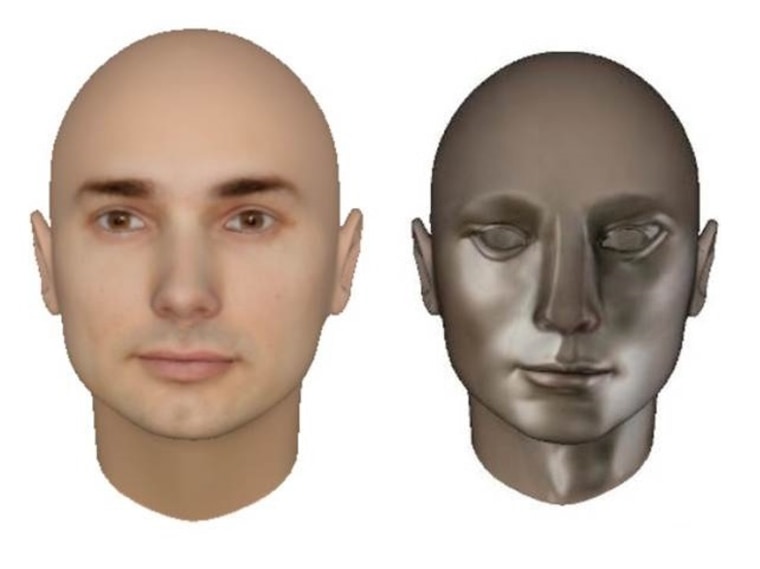

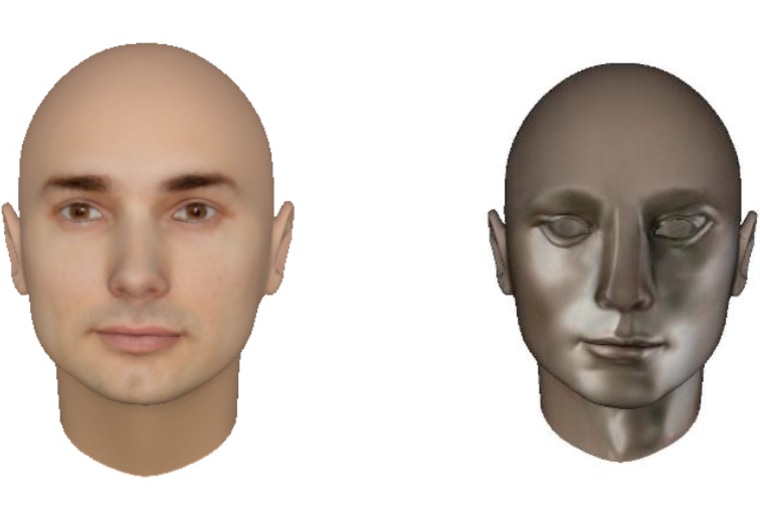

Each volunteer got a turn with each of three robot displays. The first two displays featured faces — one with human features, eyebrows and fleshy skin tone — much like the European student on which it was modeled — and another with a silver android-like finish and blank eyes. In the third session, the volunteers checked their blood pressure checked with the help of the same PeopleBot, but this time with no display face at all, merely a voice.

Afterwards, the humans rated their experience. By far the most popular version of the assistant was the one with the most human face. But here's the surprise — the test subjects trusted the faceless robot over the one with a silver mechanical face. The silver face, they reported, though more human, was also more "eerie."

"When you can't put it in a box of being either human or a robot, that's when you're a bit uncomfortable," Elizabeth Broadbent, senior lecturer at the University of Auckland and the lead author of the study told NBC News.

Humans understood the human face to be "friendly, helpful, patient" even "affectionate." The silver face, in comparison, seemed to "lack emotion." It was "practical" but "sterile" and "enough human-like that the silver appearance becomes creepy." The faceless robot was "impersonal, mechanical and soulless," but scored higher than the silver-faced version on trustworthiness, because, as one volunteer put it: "[i]n some ways more honest because there isn’t a face and I know there is not a person inside."

"Our results show that it's not how human-like they were, but the personality characteristics that they took [away] that made it more eerie," Broadbent said.

Though there have been several studies that examine how humans react to the appearance of robots, Broadbent's study, "[t]esting the robot's appearance in a health context, a real-world context in which it might be used, is novel and worthy," Maja Mataric, professor of computer science, robotics and pediatrics at the University of Southern California, wrote to NBC News in an email.

In her view, the silver robotic face was a bit of a "straw man" because it doesn't make "one think of a 'robot,' but [rather] of a graphics agent or perhaps [a] statue." A "male-female comparison" or a comparison between a 2-D and 3-D face would have "yielded even more informative insights," Mataric wrote.

Almost since the first robots were made, researchers have wondered how best they ought to look. Among the most famous and controversial, the Uncanny Valley theory described in an essay in 1970, suggested that humans liked their robots a Goldilocks medium: not too robotic, and not too human either.

But even among robots that don't look too human — without "getting into the Valley," as robotics researchers say — humans have clear-cut preferences and responses to robot appearances.

For example, in one series of sessions, elderly adults told Wendy Rogers at Georgia Tech that they didn't mind a machine-like robot doing chores around the house, but "there was a preference for human-looking robots for tasks requiring more intelligence," Rogers told NBC News previously.

The famously emotive robot, Kismet, built by Cynthia Breazeal at MIT, is all eyes and lips and lashes. Due in part to its ability to mimic human facial expressions, children and adults who interacted with the robot see its actions as "the product of intents, beliefs, desires, and feelings, and respond to Kismet in these terms," Breazeal wrote in the International Journal of Human-Computer Studies in 2003.

While robots with real, animated faces may one day help check your blood pressure, today the vast number of robots in use are faceless (like the Roomba) or intelligent displays on wheels, like iRobot's RP-Vita, and the PeopleBot. Though "that study has yet to be done," Broadbent said that the new results would "probably generalize to a robot with a real head."

More about our future robot overlords:

- My robot friend: People find real comfort in artificial companionship

- Knight in steely armor: Atlas the robot to train in rescue

- Robot learns to recognize objects on its own

Vinayak Kumar, Xingyan Li, John Sollers 3rd, Rebecca Stafford, Bruce MacDonald, Daniel Wegner joined Elizabeth Broadbent as co-authors "Robots with Display Screens: A Robot with a More Humanlike Face Display Is Perceived To Have More Mind and a Better Personality" published in the Aug. 28 issue of PLOS ONE.

Nidhi Subbaraman writes about science and technology. Follow her on Facebook, Twitter and Google+.