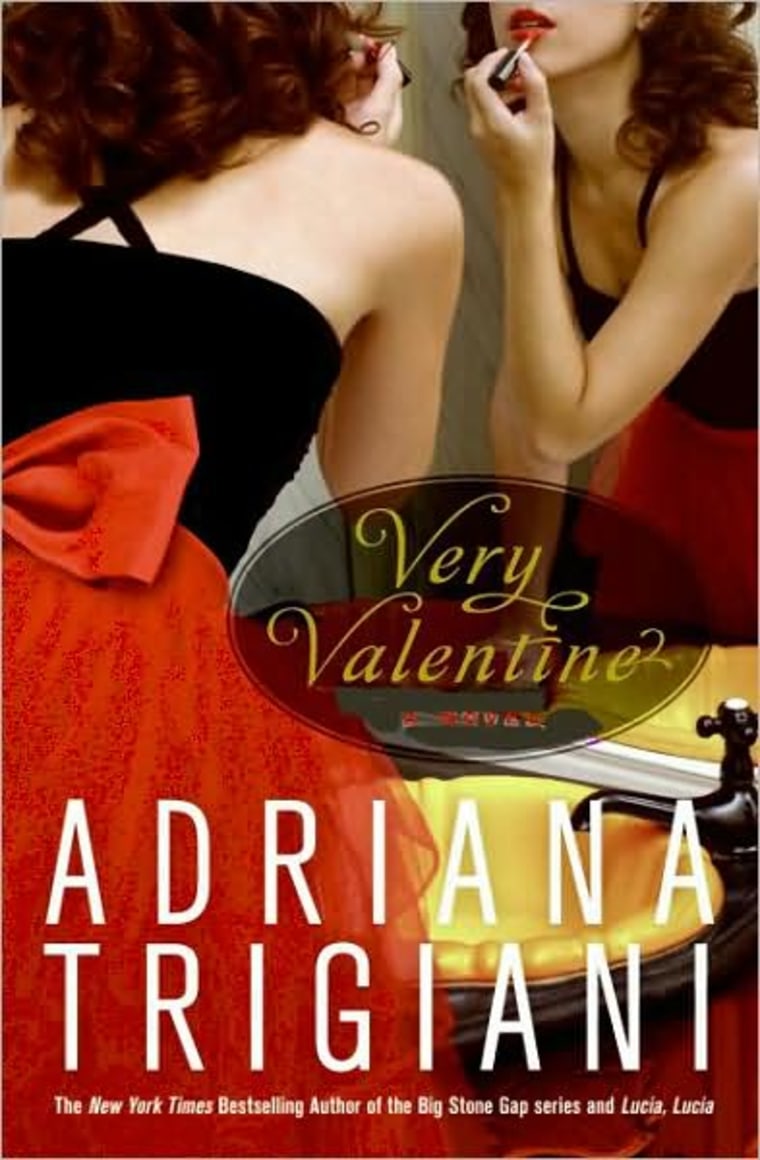

Meet the Roncalli and Angelini families, a vibrant cast of colorful characters who navigate tricky family dynamics with hilarity and brio, from magical Manhattan to the picturesque hills of bella Italia. "Very Valentine" is the first novel in a trilogy by Adriana Trigiani. An excerpt.

Leonard’s of Great Neck

I’m not the pretty sister. I’m not the smart sister either. I am the funny one. I’ve been called that for so long, for so many years, in fact, that all of my life I thought it was one word: Funnyone.

If I had to die, and believe me, I don’t want to, but if I had to choose a location, I’d want to die right here in the ladies lounge at Leonard’s of Great Neck. It’s the mirrors. I look slim-sational, even in 3-D. I’m no scientist, but there’s something about the slant of the full length glass, the shimmer of the blue marble counters and the golden light of the pave chandeliers that creates an optical illusion turning my reflection into a long, lean, pale pink swizzle stick.

This is my eighth reception (third as an attendant) at Leonard’s La Dolce Vita, the formal name for our family’s favorite Long Island wedding factory. Everyone I know has been married here or, at least everyone I’m related to.

My sisters and I made our debut as flower girls in 1984 for our cousin Mary Theresa, who had more attendants on the dais than guests at the tables. Our cousin’s wedding might have been a sacred exchange of vows between a man and a woman, but it was also a show, with costumes, choreography and special lighting making the bride the star and the groom the grip.

Mary T. considers herself Italian-American royalty, so she had the Knights of Columbus form a crossing guard for our entrance into the Venetian Starlight Room.

The Knights were regal in their tuxedoes, red sashes, black capes and tricornered hats with the marabou plumes. I took my place behind the other girls in the procession as the band played “Nobody Does It Better,” but I turned to run away as the knights held up their swords to form a canopy. Aunt Feen grabbed me and gave me a shove. I closed my eyes, gripped my bouquet, and bolted under the blades like I was running for sane.

Despite my fear of sharp and clanging objects, I fell in love with Leonard’s that day. It was my first Italian formal. I couldn’t wait to grow up and emulate my mother and her friends who drank Harvey Wallbangers in cut crystal tumblers while wearing silver sequins from head to toe. When I was 9 years old, I thought Leonard’s had class. Never mind that from the passing lane on Northern Boulevard, it looks like a white stucco casino on the French Riviera by way of Long Island. For me, Leonard’s was a House of Enchantments.

The La Dolce Vita Experience begins when you pull up to the entrance. The wide circular driveway is a dead ringer for Jane Austen’s Pemberley and also resembles the valet stand at Neiman Marcus, outside the Short Hills Mall. This is the thing about Leonard’s: everywhere you look, it reminds you of elegant places you have already been. The two story picture windows are reminiscent of the Metropolitan Opera House, while the tiered fountain is strictly Trevi. You almost believe you’re in the heart of Rome until you realize the cascading water is actually drowning out the traffic on I–495.

The landscaping is a marvel of botanical grooming, with boxwood sheared into long rectangles, low borders of yew, privet hedges in cropped ovals, and bayberry sculpted into twirly ice cream-cone shapes. The manicured shrubs are set in beds of shiny river stones, an appropriate pre-motif to the ice sculptures that tower over the raw bar inside.

The exterior lights suggest the strip in Las Vegas, but it’s far more tasteful here, as the bulbs are recessed, giving the place a low, twinkling glow. Topiaries shaped like crescent moons flank the entrance doors. Beneath them, low meatball bushes serve as a base for the birds-of-paradise, which pop out of the shrubs like cocktail umbrellas.

The band plays “Burning Down The House” as I take a moment to catch my breath in the ladies’ lounge. I’m alone for the first time on my sister Jaclyn’s wedding day and I like it. It’s been a long one. I’m holding the tension of the entire family in the vertebrae of my neck. When I marry, I will elope to city hall because my bones can take the pressure of another Roncalli wedding extravaganza. I’d miss the beer battered shrimp and the pate rillettes, but I’d survive. The months of planning this wedding nearly gave me an ulcer, and the actual execution bestowed on my right eye a pulsating tic that could only be soothed by holding a frozen teething ring I bogarted from cousin Kitty Calzetti’s baby after the Nuptial Mass. Despite the agita, it’s a wonderful day, because I’m happy for my baby sister, who I remember holding, like a Capodimonte rose, on the day she was born.

I hold my martini-shaped evening bag covered in sequins (the wedding-party gift from the bride) up to the mirror and say, “I’d like to thank Kleinfeld of Brooklyn, who knocked off Vera Wang to strapless perfection. And I’d like to thank Spanx, the girdle genius, who turned my pear shape into a surfboard.” I move closer to the mirror and check my teeth. It ain’t an Italian wedding without clams casino dusted in parsley flakes, and you know where those end up.

My professional makeup job provided (at half price) by the bride’s best friend’s sister-in-law, Nancy DeNoia, is really holding up. She did my face at around 8 o’clock this morning, and it’s now suppertime but I still look fresh. “It’s the powder. Banane by LeClerc,” my older sister, Tess, said. And she knows: she was matte through two childbirths. We have the pictures to prove it.

This morning, my sisters, our mother, and I sat on folding chairs in front of Mom’s Golden Age of Hollywood mirror in the bedroom of their Tudor in Forest Hills, pretty (almost) maids all in a row.

“Look at us,” my mother said, lifting her face out of her neck like a turtle. “We look like sisters.”

“We are sisters,” I reminded her as I looked at my actual sisters in the glass. My mother looked hurt. “ ... and you ... you’re our teen mother.”

“Let’s not go that far.” My sixty-one-year-old mother, named Michelina after her father Michael (everyone calls my mom “Mike”), with her heart-shaped face, wide-set brown eyes, and full lips glazed the color of a terra-cotta pot looked smugly into the mirror. My mother is the only woman I know who arrives fully made up for the makeup artist.

The Roncalli sisters, minus our eldest sibling and our only brother, Alfred (aka the Pill), and Dad (called Dutch), are an open-all-night, girls-only club. We are best friends who share everything with two exceptions: we never discuss our sex lives or bank accounts. We are bound together by tradition, secrets, and our mother’s flat iron.

The bond was secured when were small. Mom created ‘Just Us Girls’ field trips; she’d schlep us to a Nettie Rosenstein retrospective at FIT, or to our first Broadway show, ‘night, Mother. As Mom hustled us out of the theater, she said, “Who knew she’d kill herself at the end?” concerned that she’d scarred us for life. We saw the world through Mom’s elegant opera glasses. Every year, the week before Christmas, she took us to the Palm Court at the Plaza Hotel for holiday tea. After we filled up on fluffy scones smothered in clotted cream and raspberry jam, we’d take our picture, in matching outfits, including Mom’s, of course, under the portrait of Eloise.

When Rosalie Signorelli Ciardullo started selling mineral powder makeup out of her trunk, guess whom Mom volunteered as traveling models? Tess (dry), me (oily) and Jaclyn (sensitive). Mom modeled for the thirty to thirty-nine age group, never mind that she was fifty-three years old at the time.

“All great artistes begin with a blank canvas,” Nancy DeNoia announced as she applied pancake makeup the color of Cheerios to my forehead. I almost said, “Anyone who uses the word ‘artiste’ probably isn’t one,” but why argue with the woman who has the power to turn you into Cher on the reunion tour via the tools in her hand?

I kept quiet as she patted the sponge on my cheeks. “We’re losing the schnoz ... ,” Nancy said, exhaling her spearmint breath as she applied small, deliberate strokes to the bridge of my nose. It felt exactly like the firm pressure applied with an ice bag by Sister Mary Joseph of the MASH unit at Holy Agony when I was hit by a line-drive baseball in seventh-grade gym. For the record, Sister Mary J. said she never saw so much blood come out of one person’s head in her life, and she would know, as she had a hitch as a nurse in Vietnam.

Nancy DeAnnoying, like an architect, stood back and surveyed my face. “The nose is gone. Now, I can salvage.”

I closed my eyes and pretended to meditate so Nancy might take the hint and stop the play-by-play of my crap features. She picked up a small brush, dipped it in ice water, and swirled it around on an inky chestnut brown square. I felt my eyebrows tingle as she painted on tiny hairs. I grew up on Madonna, and when she plucked, I plucked. Now I’m paying for it.

My face felt cold and painterly until Nancy dipped a Kabuki brush into the powder and buffed my skin in small circles, like the wax-finish feature at Andretti’s car wash. When she was done, I resembled a newborn puppy, all big, wet eyes and no nose.

In the ladies lounge, I’m taking one of many lipstick time-outs because I actually eat at weddings. After weeks of dieting to fit into my dress, I figure I deserve a round of pink ladies, all the passed hors d’oeuvres I can throw back, and enough cannolis to leave a dark crater on the lazy Susan in the center of the Venetian table. I’m not worried. I’ll work all this food off dancing to the long-play version of the Electric Slide. I fish the tube of lipstick out of my purse. There is nothing worse than bare lips with a suction cup tattoo of plum pencil around the rim. I fill in between the lines where the color has faded.

My sisters and I have played a game since childhood; when we weren’t dressing up as brides, we played Planning Our Funerals. It’s not that my parents are morbid, or that anything particularly horrible happened to us, it’s that we’re Italian and therefore, tit for tat, it’s the law of the Roncalli universe: for every happy thing, there has to be a sad thing. Weddings are for young people and funerals are the weddings of old people. Both, I have learned, take long-term planning.

There are two unbreakable rules in our family. One is to attend all funerals of any known persons with whom we have ever come in contact. This mandate includes people we are related to (blood relatives, family by marriage, and cousins of family by marriage) but also extends beyond close friends to encompass teachers, hairdressers and doctors. Any professional person who has rendered an opinion or given a diagnosis of a personal nature makes the cut. There is a special category for those who deliver, including “Uncle Larry,” our UPS man who went quickly on a Saturday morning in 1983. Mom pulled us out of school the following Monday to drive us to his funeral in Manhasset. “Respect,” she said to us at the time, but we knew the real reason. She just likes to get dressed up.

The second rule of the Roncalli family is to attend all weddings in order to dance with anyone who asks you, including icky cousin Paulie who was kicked out of Arthur Murray for groping the instructor (the case was settled out of court).

There’s a third rule: Never acknowledge Mom’s 1966 nose job. Never mind that her remodeled nose is a dead ringer for Annette Funicello’s, while we, her biological children, have the profiles of Marty Feldman. “No one will ever guess ... unless you tell them,” my mother warned us. “And if anyone asks, you simply say that your father’s nasal gene was dominant.”

Excerpted from ”Very Valentine” by Adriana Trigiani. Copyright (c) 2009, reprinted with permission from HarperCollins. To read more,