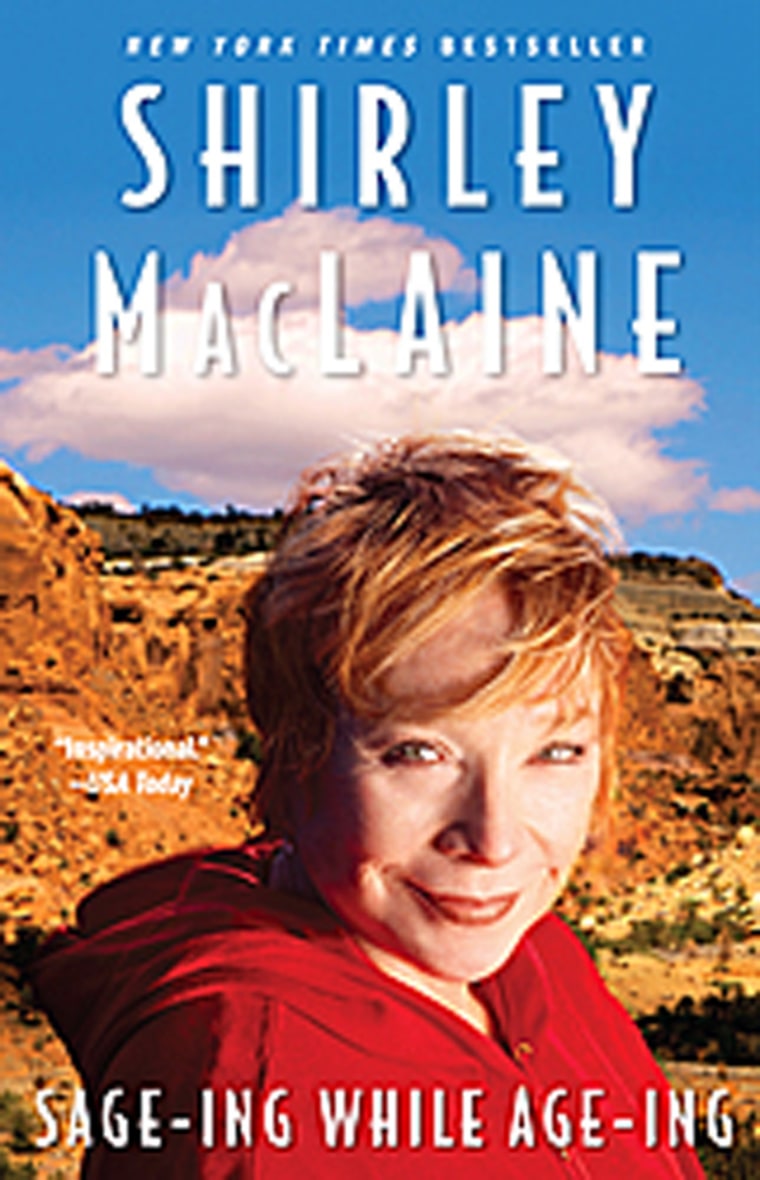

In her new book "Sage-ing While Age-ing," actress and writer Shirley MacLaine shares her experiences and personal insights she's learned over the years, from politics to nutrition to spirituality and more. An excerpt.

Chapter one:I'm sitting on the porch of my new house overlooking Santa Fe, New Mexico. I'm moving in and I'm exhausted from unpacking boxes, putting up pictures, and ruminating about my life. I do a lot of ruminating these days, but moving into a new house is making it more intense than usual.

The house isn't really new (it's fifteen years old) but it is new to me, and it's a dream place for me.

A house is really a life ... one you've had or one you want to have. A new dream.

Whenever I have a really good dream, I find it's usually about a house (my life) with new additional rooms (new chapters and adventures) for me to wander through.

Now, as I take a break and look out over the terrain here in the Land of Enchantment I find myself freely associating about my own "inner terrain."

It's a challenge for me to realize that I am older than I thought I was. I feel like a sage-ing "icon" (as the young people call me). I feel I must become a sage, or I can't deal with the reality of what we've allowed ourselves to become — me included.

At dinner parties these days the table falls virtually silent when I say something (anything) because the other guests expect a treatise on enlightenment. I'm told I predicted 9/11 and the erratic weather changes a long time ago. I don't remember any of it, but then I don't remember much of anything these days. The day I couldn't remember where I put my car keys was one thing. But when I finally found them and I couldn't remember what they were for, I knew I had reached the age for either sageing or an old folks' home. I picked sageing.

I've decided to believe everything I hear. Why not? It's all unbelievable anyway. I mean, most everything these days challenges what I grew up knowing and believing was a kind of sane truth.

Our president invades a country because Jesus or God told him to. Wow! And people think I'm wacky for believing in other lives and guiding spirits who channel through humans. Wasn't that what happened to W.? "I don't listen to my old man because I have a higher-powered spirit who got me off of heavy-duty 'spirits' along with drugs." Wow again! What should we honestly think about all that? Should we believe him? Maybe so. But who and what were his spirits and his gods?

Tomorrow I will start hanging family pictures on the walls of my new house. I remember that my father was a serial alcoholic who was intelligent and told the truth. In fact, I respected him for the reasons why he drank. He couldn't bear the hypocrisy he saw all around him.

He told me about the out-of-body experience he had when he cracked up the car. He said he went out of his body and met with his own father and mother again. He said he saw the light of God around them and knew that light was his real home. He wanted to go there — into the light — but something stopped him — a voice, maybe, who told him he needed to go back to his life on Earth and finish the work he had agreed to do. He said he had contracted to have his life with our family, and he knew he wasn't finished.

He never told anyone about his experience until I brought home my first metaphysical book which I read to him and Mother. (I always read my books to my parents before I published them.) He was glad to talk to someone about it. I knew how he felt — it had happened to me in Peru when I sat on a mountaintop in the Andes and left my body to witness the Earth below me. Was I crazy, I wondered, or was I liberated from limitations? Dad went on to tell me that he had seen his best buddy appear at the foot of his bed at the exact moment that he died in World War II. I remember asking him if he thought anyone ever really died. He looked at me with a quizzical expression but didn't say anything in reply.

Maybe death is as exciting as life. Maybe war is a karmic dance between the killers and the killed and no soul ever really dies. If that is so, then what is the point of war? Is the real reason for war to teach us the karmic steps of the dance until we are exhausted by it?

My dad had as many questions as I did. He loved philosophy and psychology. Questions like: Are we alone in the universe? Why are we here? Why are we the way we are? What is energy? Is there life before life?

He always asked himself those questions and never stopped me from asking mine. He was kind of a hometown philosopher.

I loved that about him. He had a hard time understanding why people behaved the way they did, with such subterfuge and hypocrisy. He would always tell the truth, even to his own detriment. For example, during his days selling real estate he would tell a prospective client that the water pump didn't work or a new roof was needed, then wonder why such disclosure blew the sale. He couldn't understand why truth was such a deterrent. He was an educated man who wrote unfinished dissertations on philosophy and psychology at Johns Hopkins. He never finished because he was ridiculed by one of his professors. I remember reading one of his papers on music. In it he said he could prove that notes had the same vibrational frequency as colors. He didn't know then that he was talking about the human chakra system, but he was. And when I told him about the seven notes on the scale corresponding to the seven rainbow colors of the chakra system, he welled up with tears. He was trying to prove something intellectually that he knew was true intuitively. He was very patriotic and used to cry at the "Star-Spangled Banner," too.

Mother was a Canadian by birth and Daddy loved showing her around the Washington Monument, the Capitol, White House, Lincoln Memorial, etc., while she was studying to become a citizen of the United States.

Mother didn't show the emotional passion Daddy did. (She was a Canadian, after all.) Her love was for nature and regrowth in the spring. She said that was why she partially understood the theory of reincarnation. Same soul, different life every rebirth. Same bush, different rose every spring.

Neither of them ridiculed my questions, my expanding beliefs, or my tendency to expound on such things in public. They used to say, "Well, it could all be true."

Daddy told me he secretly always wanted to run away and join the circus. He was a good musician who played the violin, but turned down a scholarship in Europe because he didn't want to study hard to become a professional musician only to end up playing in the pit of a Broadway musical eight times a week. Hence, later on, he became a real estate salesman. I think I'm good with the value of real estate because of him. My agent used to say that because of my investments in real estate, I have lived rent-free my whole life.

Mother was an artist, an actress, and loved to read poetry. Her mother was the Dean of Women at Acadia University in Wolfville, Nova Scotia, Canada. And Mother's father was a brain surgeon (one of the best in Canada, I'm told) and as I found out later, going through the attic after they both had passed on, her father was a thirty-third-degree Mason! I found newspaper articles that she had saved attesting to that fact, but she never told me herself. Maybe she didn't even know.

She did tell me, though, that she was at her father's side when he died (she was seventeen), and at his passing he said to her, "Oh, it's sooo beautiful. Don't be sorry, it's incredibly beautiful." So I suppose I got my spiritual and metaphysical leanings from both my parents.

I guess we could say that belief is a result of our imagination. But then perhaps we are imagining we are alive, as the Buddhists propound. We dream our lives during the day, and night dream them when we sleep. The trick is to avoid the nightmares of each by understanding who we really are. I've always liked Einstein's quote, "Imagination is more important than knowledge."

As I look back over my life, as my mind wanders freely over how I've lived and loved and protested and questioned, I realize that aging well isn't about the search for happiness, but more about quietly feeling content with what I've experienced. Loving without caring too much, you might say. And more than anything, I've come to appreciate the value of conflict. Everything isn't always meant to be light and love. The dark times, the conflicts, that's where real learning can happen.

For example, during the Great Depression my family never had more than $300 in the bank, and we were taught to save for the future because one never knew when it could happen again. I remember I was confused over the declaration of war I heard Roosevelt announce through the old-fashioned radio in the living room as we gathered around trying to understand what "infamy" meant. I wept over the death of Roosevelt as I was coming up the back stairs of our house in Richmond, Virginia. I loved the "victory gardens" we were taught to till every weekend to be rewarded with ice-cream dinners on Sunday nights.

I survived the move from Richmond to Arlington, Virginia, where my classmates made jokes about how Arlington was a place where people were "dying to get in." I went through giving book reports in my below-the-Mason-Dixon-line accent until I finally talked like everyone else.

I lived the excited pangs of independence and loneliness when at the age of sixteen I went to New York City to study ballet and whatever else the city that never slept had to offer. I had been dancing since I was three and had some pretty good teachers, but NYC was the ultimate. I got into the subway circuit show of Oklahoma! and discovered I loved musical comedy more than ballet. When Rodgers and Hammerstein asked me to join the London company, my dad was disappointed that I wouldn't finish high school, so I turned Rodgers and Hammerstein down and went home to graduate. I've never regretted that, although I never learned much in school except how to type.

My high school was about cheerleading, football games, dancing classes, and boys. When I graduated and went back to New York, I was ready to succeed. I got into a Servel Ice Box trade show and danced accomplished pirouettes around a Servel Ice Maker. It was so boring that one night I blacked out my two front teeth for a joke and got fired. We had traveled around the country with the refrigerators on a train, so I learned about stage door johnnies who wanted their drinks straight up, never mind the ice, and could they have the pleasure of experiencing a "showgirl"? I said, "No, I'm a dancer."

After Servel I got into Me and Juliet, another Rodgers and Hammerstein musical, where I settled into being a Broadway gypsy and rode the subways to and from the theater because I had only enough money for lunch and dinner at the Automat, usually a peanut butter sandwich (10¢) and lemonade (lemons and sugar free at the tables). The chorus line was a family to me, but I knew I wanted to be out there singing a song and acting. The opportunity soon came when Hal Prince and Freddie Brisson came down to the basement where the chorus kids dressed and asked if any of us wanted to invest in a new musical they were putting together called 7½ Cents (later renamed The Pajama Game). I said I couldn't afford an investment, but would like to audition for the show. They said fine.

A few months later I found myself dancing in front of Jerry Robbins, George Abbott (who had directed Me and Juliet), Hal Prince, and a strange, hunched-over little man who smoked cigarettes incessantly and paced up and down the aisles of the St. James Theatre in the dark. I remembered he was married to Joan McCracken, one of the stars of Me and Juliet. I also remembered him from Kiss Me Kate on the screen. He played the snake and a court jester. He was Bob Fosse, and our lives were to be inextricably intertwined. When Jerry Robbins pointed to me and said, "You with the legs that start at your eyeballs," I knew I was in.

Carol Haney (who danced with Bob in Kiss Me Kate) was the hit of The Pajama Game when we opened a few months later. She had no understudy, and Hal Prince asked me if I would like to try. In those days, I was dancing with a long, red ponytail whipping around my face — that is, until the stage manager dunked my head in the basement sink and said, "Cut it off. You are attracting attention away from the principals!" Hence my hairstyle, which I've never changed. So much for my sense of keeping up with fashion.

Anyway, they gave me the understudy job, but I never had a rehearsal. I had thought Carol would go on with a broken neck, so I had decided instead to understudy Gwen Verdon in Can-Can at the Shubert Theater down the street. Then, a few nights later, Carol sprained her ankle.

Synchronicity was already beginning to become active in my life, as I was about to learn.

I had my "I'm leaving" notice in my pocket when I arrived at the St. James. Across the stage door entrance stood Jerry Robbins, Bob Fosse, Hal Prince, etc. "Haney is out," they said. "You're on." I couldn't believe what I was hearing. "I'm on? Without a rehearsal?" I didn't know what key I sang in, I didn't know the dialogue or the lyrics, and I didn't know whether Carol's clothes would fit. I had been watching her from the wings, but performing something with your own body is another matter. Even with the aforementioned problems, all I could think of was, "I'm going to drop the hat in Steam Heat" (Fosse's famous hat-trick number).

I raced to Carol's dressing room. Her clothes fit me except for her shoes. I had a pair of sneakers with me from an afternoon at Jones Beach. They needed to be black. The wardrobe mistress dyed them (the black water dripped from them when I put them on). John Raitt and the conductor, Hal Hastings, wincingly went over the songs with me. With my voice, it didn't really matter what key I sang in.

There I was, waiting in the wings, when the announcer said Carol Haney would be out and I would replace her. There were "boos" from the orchestra to the second balcony. Some people threw things at the stage. The cast was lined up in the wings to observe the debacle. And I waited for the curtain to rise.

I think it was then that I realized I had an angel on my shoulder. I felt I was guided somehow. I didn't know how or by whom. But I wasn't alone. I sank into the center of my being and somehow did the show. The rest of the cast was sensitive and on their toes for any trouble I might find myself unable to handle.

I did drop the hat in Steam Heat because the spotlight blinded me. I lost it in midair, and said, "Oh s--t," right out loud. The first few rows gasped and crossed their legs, but I got through the rest of it without falling into the pit. When the show was over, I took my bows with the other two Steam Heat dancers. The audience stood up. Buzz Miller and Peter Gennaro peeled off and left me in the center of the stage to bask in the audience's appreciation. Never had I been so lonely, but I knew deep inside that the destiny of my life was now in alignment. My shoulder angel smiled, and I knew I was in for a life of hard work, discipline, gratitude, and success.

I also knew somehow that I would forever be curious about those things that were "unseen" but definitely real. They were alive and well and active in my life. I would come to understand them years later.

Hal Wallis, a movie producer, had been in the audience and came backstage to ask for a meeting with me. I remembered his name from "Hal Wallis Presents Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis" (more synchronicity: the Rat Pack with Dean and Frank later).

Wallis took me to dinner, where I nearly ate the menu, too. He invited me to do a screen test with Danny Mann (the director who guided Shirley Booth and Anna Magnani to Academy Awards).

When I showed up for the screen test, Danny asked what scene I would like to do. I told him I didn't know any, and I didn't know anything about acting anyway. He asked someone for a high stool, then told me to sit on it and we just talked. I did a few steps with a long scarf and sang something quietly so he wouldn't be able to tell I couldn't sing. He smiled through it all, and I guess I did, too.

Wallis saw the test and signed me to a contract saying, "The personality test has come into being. .. no more scenes from Voice of the Turtle."

Somehow, what was happening to me seemed natural. It was as though it was in the flow of what was supposed to be — a kind of predetermined destiny. Dear Reader, in some metaphysical way I knew I had planned it all before I was born! I really felt that way, and at that time I didn't know what the word "reincarnation" meant. I just knew I had designed it before I came in.

I went on for Carol in The Pajama Game for about two weeks. Those weeks were a blur of learning. I rehearsed in my sleep, literally, whereupon I became aware of living on two levels of consciousness simultaneously (a state of being I employ often, by the way).

I had never been a religious person. I had gone to church a few times, and I think it said "Baptist" on my birth certificate. But at an early age I was aware of another dimension. It was invisible, but real to me. I had dreams of being guided from another place. I knew there was another, larger truth than what I had been taught.

When I was ten, I asked for a telescope for Christmas — a telescope and a gold cross on a chain. I used to sit out on our lawn, gaze through that telescope, and ponder on life out there. What was happening on those other stars? Were there star people who gazed down on me? I wanted to know them, feel them, ask them questions. There was never any doubt in my mind that they were there. Maybe one of them was the angel on my shoulder.

The gold cross on a chain (which I still have and treasure) was with me when I went to New York. One day I felt it missing from my neck. It was gone. At that moment I heard a voice in my head say, "Southeast corner of Fifty-seventh Street and Seventh Avenue." A voice? In my head? I took the bus to that location, got off, and there, gleaming in the sunlight, was the cross. "What's going on here?" I thought. "What ... or who ... is talking to me?"

My childhood seemed to have been normal. I guess I had a vivid imagination. Yet, I knew I perceived things differently than most of my friends. I was a happy-go-lucky student who wanted to be popular and smoked with boys in the backseats of cars, but subjects such as geometry and astronomy became my preferred pleasure. I felt I was remembering an acquaintance with such things. The books I read had to do with "Heroes of Civilization" who had gone out on a limb for their curiosities and beliefs. They were who I identified with — not show business people and dancers. I did have a crush on Alan Ladd until I met him and saw that he came up to my waist. And I adored Nora Kaye, who could do sixty-four fouettés and also act as well as she danced in Fall River Legend. When she was one of the producers of The Turning Point, I came to love her as a human being (more synchronicity). I told her of the time as a twelve-year-old I went backstage to see her. Because Kaye had an E on the end of her name, I thought she must be Russian and unable to understand English. Instead, she burst forth with a Brooklyn accent and invited me to sit on her lap. She remembered.

Yes, I was beginning to see the connections of synchronicity in my life, particularly the show business events. It was as though I was meant to be successful so I could contribute in other ways on a public stage when I understood them better. For example, Bob Fosse picked me out of the chorus of Pajama Game to sing a little part, then appointed me Carol's understudy. A few years later, Lew Wasserman, head of Universal Pictures, called me into his office (I remember his desk was completely empty and clear) and asked me what I wanted to do next. I answered, "Sweet Charity. And Bob Fosse should direct it." Lew said Bob was just a choreographer. I said, okay, but so was Stanley Donen. Lew agreed and sent for Fosse.

The experience with Fosse on Charity was magical. Of course he apologized through swirls of cigarette smoke for making us "do it a few more times." But he was brilliant, and it launched his picture career. When Bob made All That Jazz, he asked me to play Gwen. I told him I couldn't dance well anymore. He kept insisting, saying I was the only authentic one who could do it after all we had been through together. I said, "How can you call All That Jazz authentic when the leading man (you) dies at the end?" He thought a moment, and said, "If you play Gwen, I promise I'll be dead after the first preview!"

After I returned from visiting Fidel Castro in Cuba, Bob visited with me again to try to convince me to play Gwen. The pleading didn't last long. What he really wanted to know was whether I had been to bed with Fidel. I told him not only did I not sleep with the man, but when I returned to New York, my Cuban maid unpacked my bags, saw pictures of me with Fidel, and promptly quit!

Bob didn't die after the first preview of All That Jazz, but he did die in a more synchronistic way that made my heart turn over. He had come from a rehearsal for the revival of Sweet Charity and died on the street in Washington, D.C., not far from my old dancing school. My teachers watched it happen.

When I did my first one-woman show, it was Gwen who came to coach me in the rehearsal hall on the new kinds of dances. And later she played a cameo in a picture I directed called Bruno. We had many chats about the many sides of Fosse and what he had meant to us. I had a dream about Gwen on the night she died. She was waving at me and smiling. I believe she and Bob were in my soul group. It is said that there are twelve people in each soul group. (In numerology, twelve is the number representing the divine.) The group is composed of people we have known in other lifetimes and who facilitate each other on the soul's path of learning. Life, I was beginning to understand, is meant to enable each of us souls to learn who we are and why we act the way we do. Hopefully, by the time we leave, we've learned a little more about our fears, our happiness, and mostly, how to give love and accept it, without judgment.

Maybe that's why I love show business: We are essentially the producer, director, and star of our own comedy/drama every day, on and off the stage of life. We are all actors on our own stages, creating our own reality. The Fosse years in my life, peopled by his own actors and actresses, who overlapped mine, enabled me to accept and even revel in talented eccentricity. Fosse was an artist whose tortured soul drove him. He never believed he was good enough, funny enough, inventive enough. He never believed he could really love enough or accept love enough. He was painfully broad-stroked and honest in his assessment of himself in All That Jazz. He was obsessed with sex and its meaning in his life, and was threatened deeply by the recognition of the feminine in himself. Underneath, he was a kind, generous, sensitive human being who was addicted to showing the world the obsessive side of himself. Out of these complex neuroses came his great art. His dance movements turned in on themselves just as he did. Unless he was expressing sex. Then they looked like his fantasy of an orgy. The Fosse years taught me that we could use our depraved opinions of ourselves to artistic advantage.

My life in films has been basically an education in human behavior; not only in terms of acting, but also in the science of trust. The Billy Wilder/Jack Lemmon years were instructions in comedy. Irma la Douce and The Apartment were acts of pure trust on the part of Jack and me. We never had a completed script when we started, but Jack had a track record with Billy, and I was new to the equation. Billy trusted the chemistry between Jack and me, and we trusted his judgment. Frankly, I didn't know enough not to trust.

Trust is an important currency in filmmaking. Trust is required in show business as much as talent and the money to finance.

We have to trust our instincts, and we have to trust each other. That is what is meant by a "collaboration."

When I was younger, I innocently trusted nearly everyone and everything. I think I still do. I'm proud that I haven't become jaded or cynical. Instead, I've become a more sophisticated questioner. Given some of my traveling antics, I don't know how I survived. I was caught in a coup d'etat in the Himalayas (Bhutan). I got smuggled illegally into Leningrad University in the Soviet Union and had my passport stolen. I lived with the Masai in East Africa and birthed a few babies inside of a menyatta (village) who were named after me. I took a women's delegation to Communist China (before any other foreigners were admitted) and promptly, along with everyone else, got pneumonia. I traveled alone across the United States and took up with an Indian medicine man in Arizona, who taught me the ways of the Great Spirit while driving around in an old Dodge with $50,000 worth of turquoise jewelry he tried to sell me. Once after a trip through Romania and Czechoslovakia, I came back to Los Angeles but never returned to my house. I turned right around, went back to the airport, and flew to Mexico. I never wanted to stay in one place except to make a movie. In fact, I canceled two movies in order to trek the Santiago de Compostela Camino alone for a month, while my agent back home wondered if I'd ever work again. I went to India for a week and stayed for a month and a half. The wanderlust was an elixir for me. I always went alone and splashed up against totally foreign environments. I learned about myself. In North Africa I studied the Koran outside of mosques with friends I met. In India I studied the Bhagavad Gita while wondering if I had lived there before. Always I was in the search for this "other" truth, this "other" dimension I knew was there. Perhaps in the older, ancient cultures of foreign lands I could find a hint of something besides stardom, success, materialism, and the action of Hollywood and America. In Brazil, I had a friend with a private plane who took me to many of the psychic surgeons and healers in the Amazon. I saw that they were working with the "other" dimensions. I saw them take out human eyes to restore sight to a blind woman. One psychic surgeon removed a human heart, fixed the four-part bypass, restored it to the man's chest, and with "energy" closed the wound without stitches.

I went to Machu Picchu in Peru with a man who said he had had a love affair with an extraterrestrial. He said he was still being guided by her and could call on that guidance anytime. He proceeded to do just that. The Peruvian roads are steep, narrow, and dangerous. He took his hands off the wheel, closed his eyes and the car was "driven." I don't know by what. People don't believe me when I tell them this story. They suspect a trick of some kind, but I saw none. What was even more shocking than the invisibly driven car was the fact that it was okay with me. I trusted that what he said was true. I believe now that I never got in serious trouble or a life-threatening situation because I trusted whoever I was with. Even if some had been life-threatening, I chose to regard them as adventures. Why did I do that? Why wasn't I more left-brained suspicious about so many events? Was I totally gullible? If so, why wasn't I ever really hurt or seriously threatened? Was there really an angel on my shoulder from the beginning? And was the real lesson in life to trust that each of us has one or maybe more angels and guides? Was I talking about religion here, or was I talking about the "other"? Real spirituality did not occur to me until I was forty years old.

Now it's a few days into my chaotic move, and I'm taking a break from unpacking and am watching the 2006 midterm election returns on television. Does America have an angel on its shoulder, I wonder? Although I am a senior citizen who has happily adopted New Mexico as my home for the rest of my years, I was born in Richmond, Virginia. I was raised in the state of Virginia, responsible for eight of our presidents and through which the Mason-Dixon line, dividing the North from the South, runs.

I see now that the people of Virginia will make the decision as to whether the Democrats will control the Senate as well as the House of Representatives. I am proud of that.

Virginia was responsible for my connection to the deep meaning of the Founding Fathers and their intent for a new democracy. Virginia was why I became a political activist. Virginia was why I got deeply involved with the civil rights movement. And later my home in Arlington, Virginia, was across the Potomac River from the nation's capital, close enough for me to observe what went on in Washington, D.C., because I took the bus from Arlington every day to go to dancing school in Washington.

Now as I sit here in New Mexico watching democracy at work, I reflect on how depressed I've been in the last year about what's been going on in Washington.

I have always had an innocent, bouncy, adolescent slant on life — optimistic and maybe even naive. It has served me well, but now I'm not so sure. I always felt that everything happens just as it should — usually for the purposeful good. Now I'm feeling more deeply the need to take greater personal responsibility for what happens in this world and thinking about how I might be participating in the reality before me, not just observing it. I find myself concerned about the addiction to technology in our culture and the crippling of democracy.

To tell you the truth, I feel like democracy. I need to be helped and nurtured along so that I will retain my faith in freedom and the goodwill of people. I need to be helped down the steps of my trailer on a movie set (someone always comes to help whether I ask for it or not). I am helped in and out of cars — cars that are racing along a street that is so wired with modern technology that I wonder how the trees and birds can take it.

Now I find myself worried that the voting machines are being tampered with and that technology has swamped and crippled democracy. Technology has sometimes made my life unbearable. I can't remember my cell phone codes, my bank codes, my pin numbers, or even the phone numbers of my family and best friends because they are stuck in some other "convenient" technological contraption.

When I waited in line at United Airlines only to be told I had to check myself in via computer, I turned around and went back home. I believe Stephen Hawking is correct when he speculates that computers will surpass human intelligence soon. Technology is even making democracy obsolete because we really don't talk to each other much anymore and debate the issues of the day. Most people are on the computer. Not me. I only use a computer to read out-of-state and international newspapers and check in on my website. Nor do I use email. If someone wants to get in touch with me, I want to hear his or her voice. I want to hear the spaces between words; the hesitations when discussing something, the emotion in their voice. And more than anything I hate email computer English. No wonder newspaper reading is way down. People don't know how to read proper English anymore.

Ever since our invasion of Iraq I have been ashamed at how we Americans have mishandled ourselves, our government, and let democracy and our Founding Fathers down. My rage and futile ranting and raving within make me feel old. What happened? How did it all come to this? We have to be saved by the state that was the home of most of our Founding Fathers?

I watch the returns with a feeling of wise resignation.

My dad always teased me about being a bleeding-heart liberal who would join any cause for an underdog. "Stick to your own little row of potatoes," he would warn, but I couldn't play it safe that way. I had the blood of the Founding Fathers pounding through my heart. The pounding was accompanied by the understanding that most of our Founding Fathers had been transcendentalists. They were metaphysically and spiritually motivated. They wanted freedom from the constraints of religion in Europe. Most were Masons, some believed in reincarnation, and Jefferson even wrote his own Jeffersonian Bible, decrying how the Christian religion had been so prostituted.

Because of my patriotism and my Virginia upbringing, I was always interested in what our government was up to. I couldn't bear Richard Nixon and his lies, particularly about Vietnam, so I spent a year campaigning for George McGovern, much to the ridicule of my dad. He said McGovern had Novocaine in his upper lip and sized him up as a real loser. He said he knew Richard Nixon was a son of a bitch but that he was our son of a bitch. He couldn't see McGovern standing up to the Communists or understanding power in any way. I saw McGovern as a senator who didn't believe we should be in Vietnam. Bobby Kennedy once said of McGovern, "He's not the most honest senator we have, he's the only honest one we have."

For me, the experience of campaigning taught me about America, because I went everywhere. I made speeches in front of union hall members, chaired coffee klatches in too many living rooms to remember, did every TV show that would have me, registered voters on the street, marched in any anti-war demonstrations I could find, and turned down every movie that came my way. I was out where Hollywood was concerned. They thought I was crazy to give up show business in favor of McGovern. Many supporters deserted George's ship, knowing it was indeed a lost cause, but for some stalwart reason, still not completely clear to me, I stuck it out to the very end. It wasn't just blind loyalty. I couldn't live with a president who corrupted the Justice Department, the Defense Department, the Oval Office, the FBI, and CIA and who also thought he could get away with treason. That was it — I thought Richard Nixon was guilty of treason and should be impeached even before Watergate was big news.

So sitting in the living room of a hotel suite in South Dakota with McGovern and a few others, I watched the country turn on him — all but Massachusetts — the state of the assassinated ones. It was awful. It was shocking. I could picture my father's "Tsk tsk, I told you so," back home in Virginia, totally unaware that his son of a bitch would disgrace our country and the presidency in another year. After the last soul-searing returns came in, I fled South Dakota and traveled south in a car with a friend. When we reached Texas, he said he missed the cement and action of New York and left. I continued driving. Alone.

As soon as I crossed the Texas border into New Mexico, I knew the license plates were right. "The Land of Enchantment" was enchanting. I made friends with some people and asked why there was so much white salt on the mountains above the desert.

They explained diplomatically that the white was snow. I was in heaven in high desert country. I knew then I would spend the last part of my life here. I had some things to do first, but until then I knew where I belonged. So here I sit, all these years later, above the Land of Enchantment, sageing over my life and our country and wondering if I really have the courage to go into who I really am. What will that journey involve?

In my home, I have what my friends call the "wall of life." It is a wall of pictures ranging from my childhood until now. I take these pictures with me if I move into a new place, and it's always fun to hang them — like pieces of a jigsaw puzzle, they fit together to cover an entire wall.

When I have people over, it's always a kick for me when they stop and stand in front of my wall of life and take it in. They see pictures of me as a young dancer, on the sets of my films, me chatting with Gorbachev, Jimmy Carter, Indira Gandhi, the Dalai Lama, George McGovern, and a prime minister or two with whom I had affairs during my "slumming in power" days. When I see photographs from my childhood, I remember that somehow I knew at the age of three in a dancing class that my life would take me around the world and back so many, many times. Dancing and show business became a springboard to everything else I wanted to accomplish in my life.

Excerpted from "Sage-ing While Age-ing." Copyright (c) 2008 by Shirley MacLaine. Reprinted with permission from Atria Books.