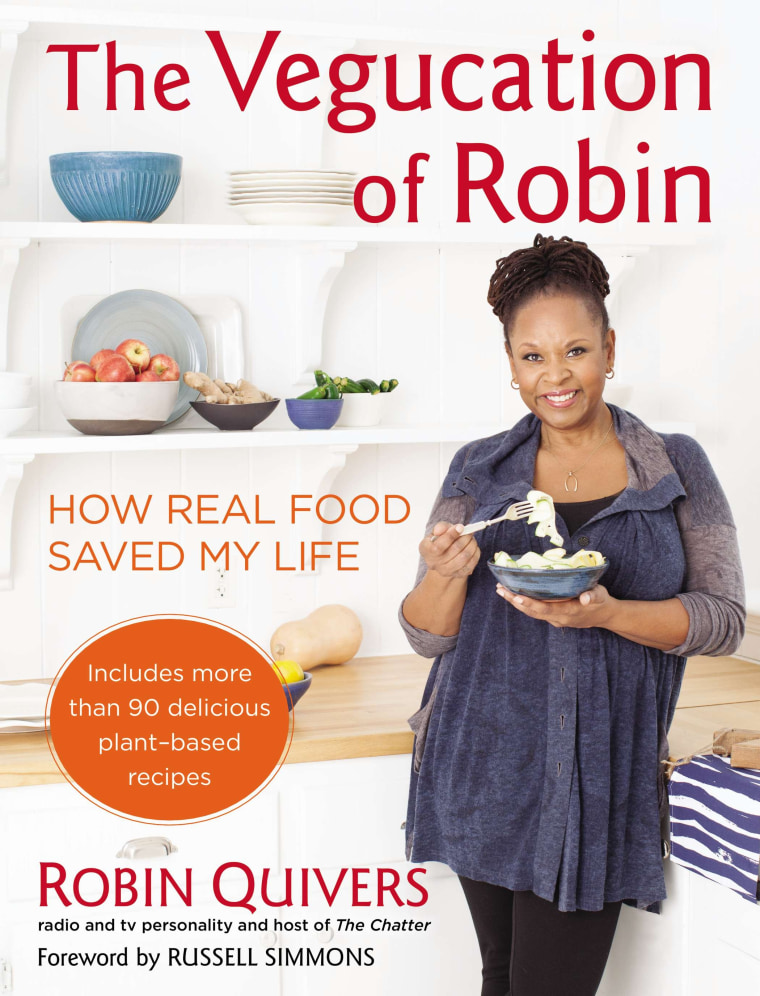

Best known as the more even-tempered, reasonable foil to Howard Stern, radio personality Robin Quivers shares details of her struggle to live a healthier by changing her diet in "How Real Food Saved My Life." Here's an excerpt.

Fat and Sick Is Not Your Destiny

When I was little, I would watch my grandmother take a needle and jab it into her leg. My mother explained that she was a diabetic and had to take insulin every day. My grandmother died when I was twelve. By the time my mother was fifty, she too was diagnosed as a diabetic and had to start sticking herself with insulin. My father had high blood pressure and heart disease. I figured there was no way I’d avoid that path—I had the trifecta.

Most of us just accept illness as our lot in life. The older we get, the more aches and pains we have and the closer we are to living out the destiny that we think is dictated by our genes or age. We see ourselves as devolving instead of evolving. When was the last time you ran into someone and he didn’t complain about knee pain or a bad back or arthritis or lament that “I’ve lost that” or “Guess I can’t do that anymore” or “I hope I can hang on to what I do have for as long as I can because I know it’s going”? Or how about my favorite, “I’m just falling apart”? It seems like everyone I know is always being knocked out of the game with something. I recently was sitting at a table with a group of men in their fifties and sixties, and they were going around comparing when they had had their bypass surgeries—like it was some kind of milestone or right of passage. And everyone’s got cancer. It’s like you get your diploma when you graduate from college, and when you hit middle age you get cancer. It doesn’t have to be some natural event that just happens. But we accept that.

Robin Quivers' post-9/11 healthy diet gave her strength to beat cancer

People assume that the older they get, the crummier they’re going to feel. They hear it all the time—their grandparents or parents are walking around saying, “Oh, I used to be able to do that, but now I can’t. I guess I’m just getting old.” So they think it’s inevitable that one day their bodies will fail them. They think it’s only a matter of time before their joints don’t work the way they’re supposed to, their eyes don’t work the way they’re supposed to, their brains don’t work the way they’re supposed to, their hearts, their bones, their pancreases, even their cells! I don’t like telling people how old I am because I don’t want to be defined by other people’s expectations. A couple of years ago I started taking Pilates lessons. I’d see my trainer once or twice a week, and she’d put me through all the machines and exercises—pretty rigorous workouts. Around that time People magazine ran before-and-after photos of my transformation, and when I came into my next session, my trainer said, “Oh my God—I saw your picture!” And I said, “Yeah, I used to weigh a lot more.” And she said, “No, it’s your age! If I knew your age I would have never worked you as hard. You’re older than my mother and I’d never have her do the things you do.”

We’ve gotten really good at just accepting that our bodies will fail us. The same thing happens with what we think of as “everyday conditions.” They’ve become so common that we don’t even call them diseases anymore. I have to chuckle when I hear, “Oh, I’m just one of those people who has hay fever” or “I’m just one of those people who gets migraines.” And I love some of these new maladies; they’re so funny! Restless leg syndrome—what’s that? Dry eye syndrome—huh? Acid reflux disease? What happened? The caveman didn’t have dry eye syndrome. He didn’t have restless leg. And if he did have acid reflux, you can bet he’d never eat what gave it to him ever again. But commercials on TV tell us that not only are these things customary but that there’s a pill for that too! So we accept it as our lot in life. We accept that we just have to live with it. Or worse, we assume technology or science will fix it. My sister-in-law Mary kept waiting for doctors to solve her problems. She didn’t think she could do anything for herself, and so she just suffered, getting sicker and sicker and sicker until she eventually passed away. It doesn’t have to be that way.

When I was twenty-eight, I went to the doctor for a regular checkup. I was in terrible shape—I was overweight, I smoked, I had frequent panic attacks. The doctor told me I had a month to get my blood pressure down, but if that didn’t work, I’d need to go on meds. I didn’t want to take a pill for the rest of my life, so I put myself on a diet and started a walking program.

It wasn’t a straight line from there to total health, but I refused to accept a chronic disease or constant aches and pains as my destiny. I’ve watched everyone in my family go down that path. I’m the only one who said no. About a year ago, I was walking with my nephew in San Francisco. He was twenty-three at the time, and we were just wandering around the city, climbing up and down the hills. I turned to him and said, “You don’t ever want to lose the ability to do this. You never want to look at the hill and think, I can’tdo this.” I told him that I wished I could put him in the body I’d had before and then put him in the body I had now because if he could feel the difference, he’d understand exactly what I was talking about. He’d see firsthand all the things he might have thought he’d have to suffer with but he doesn’t have to.

From the beginning of my career, I’ve shared intimate nuances of my life so that others might connect with them. This is no exception. I’ve certainly aired no shortage of failures when it comes to my short-lived diets, health kicks, and weight-loss schemes; but this time it’s different. Now that I’ve finally figured out how to take control of my health and completely change my life from the inside out, I’m not going to shut up about it. Because one of the things you can’t help doing when you really feel good is running up and down the street, grabbing people and shaking them and saying, “There’s hope for you yet!” If there’s one thing I want you to walk away with from this book, it’s this: Your race does not determine whether you’re a diabetic, just as your genetics don’t make heart disease inevitable. Your age doesn’t mean bad knees are a requirement, and limitations and restrictions in your life are not a given. And while you might not have been diagnosed with a “disease” just yet, the absence of a disease doesn’t necessarily mean wellness. Look at me—I was plodding along, getting weaker and weaker and weaker, but nobody gave me a diagnosis. I was out of my mind with grief about how badly I was doing and how much life I was missing—but if someone asked me how my health was, I’d say, “Eh, not so good, but at least I don’t have a disease!” I couldn’t have been more wrong. The things we know how to prevent, we should prevent. There’s just no excuse for already being behind the eight ball when something unexpected happens. Trust me, there are enough bad things that can happen without your contribution. If I had followed my family tree, I probably wouldn’t be here to give you fair warning. It took taking control of my health to make a difference in my life, and now I’m giving you the same opportunity. Your well-being and happiness are your choice, so why accept anything less than liberating, life-changing wellness?

Reprinted by arrangement with AVERY, a member of Penguin Group (USA) LLC, A Penguin Random House Company. Copyright © ROBIN QUIVERS, 2013.