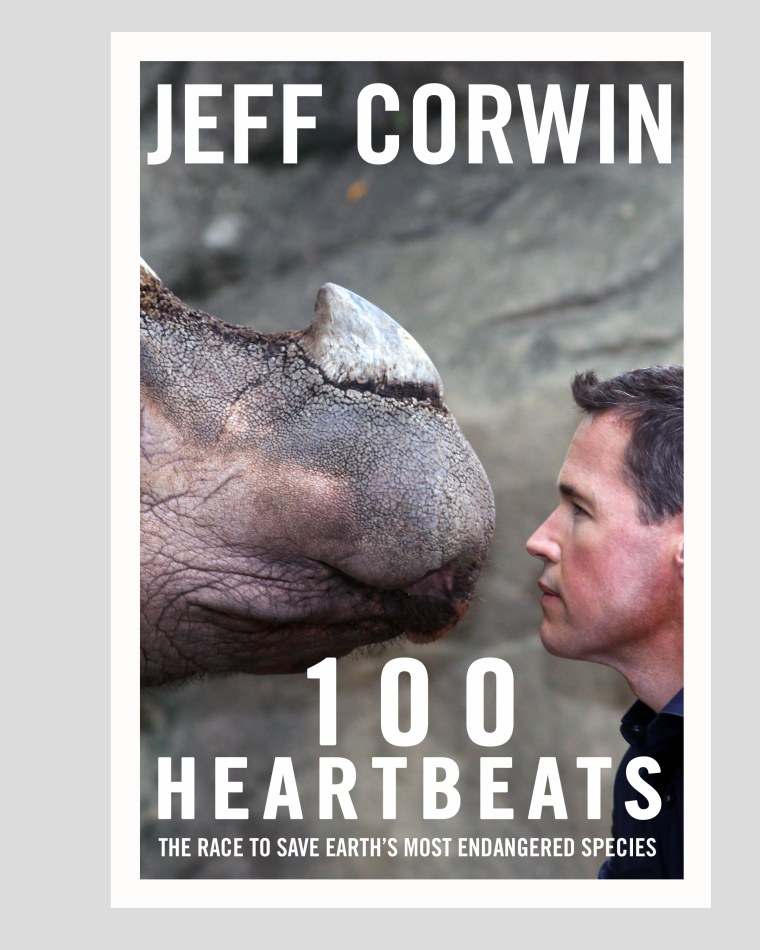

In his new book “100 Heartbeats,” conservationist and television host Jeff Corwin provides an urgent portrait of wildlife that is teetering on the brink of extinction. He also shares stories of battles being waged and won in defense of the planet’s most threatened creatures by conservationists on the front lines. Here is an excerpt.

The animal kingdom is in critical condition. The affliction isn’t a disease, but rather a crisis of endangerment that threatens to wipe out many of the world’s animal species forever.

Ironically, the only species capable of saving these animals is the same one that’s responsible for putting them in danger. The plight of the 16,928 species threatened with extinction is largely due to devastating man-made ecological changes such as habitat loss, pollution, climate change, and unsustainable exploitation.

The International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN), whose classification system is widely considered to be authoritative, classifies a species as endangered when it has experienced a population loss of at least 50 percent in three generations or 10 years, whichever period is longer. In the United States, a species is officially considered endangered under the Endangered Species Act (ESA) if it’s at risk for extinction throughout all or a significant portion of its range.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the National Marine Fisheries Service share responsibility for implementing the ESA with the goal of conserving species as well as their ecosystems. An “endangered” designation makes it illegal to hunt, harm, or otherwise kill or capture a species. Under the ESA, species are considered threatened if they’re deemed likely to become endangered without intervention. Usually, threatened species receive the same protection as endangered species. “Critically endangered” is the highest-risk category assigned by the IUCN. Generally speaking, this designation is assigned to species that have experienced or are expected to experience population declines of at least 80 percent in three generations or 10 years, whichever is longer.

The Hundred Heartbeat ClubThe animals featured in this book face varying degrees of endangerment; tragically, some of them have already lost their battle. But the stories I’ve chosen to share are those of the animals whose situations are representative of larger problems in our ecosystem — problems we can solve — and those whose loss has provided us with valuable wisdom.

The plight of the Asiatic cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus venaticus), an especially rare member of the Hundred Heartbeat Club, is symbolic of the critical condition of animals across the globe. With only 60 members remaining in the wild in Iran and an unknown but surely minuscule number in Pakistan, these powerful, graceful hunters that are a subspecies of the world’s fastest terrestrial species (Acinonyx jubatus) unfortunately can’t outrun the proverbial speeding bullet. A combination of poaching, habitat degradation, and poor genetics has conspired to critically endanger their existence.

The problems facing the cheetah date back to the last ice age, when populations were reduced so severely that today their genetic diversity is very limited. So I was elated to meet some of these beautiful, slinky creatures at a game reserve outside Lake Naivasha in Kenya 12 years ago. They were brothers who had been orphaned at 2 months old when a rancher shot their mother, and I accompanied them on their first true test of survival.

I’d spent the preceding days helping to train these brothers for the chase — the pursuit of prey they’d need to master in order to make it in the wild. The manager of the reserve had them chase lures, flashlight beams, and, to really build up their speed, a rope tied to the back of a speeding jeep. When they were ready, we drove them away from the reserve and nudged them out of our jeep. They were confused at first, probably wondering why we hadn’t brought any “toys” for them to chase. But when they caught their first glimpse of a Thomson’s gazelle (Eudorcas thomsoni), instinct took over. One brother charged after it at about 40 miles per hour, but his efforts weren’t enough, and the gazelle outpaced him. Just as the gazelle began “pronking” — bouncing more than running — in celebration of its apparent victory, the other cheetah appeared from out of nowhere to finish the job.

Their teamwork had been flawless, but they still had one more thing to learn. Looking down at the gazelle, and then at one another, the brothers didn’t seem sure of the next step. Just then the cheetah that had made the kill seemed to notice that he liked the taste in his mouth and bent down for another bite. Before we knew it, the brothers were feasting like seasoned gourmands. While they still had some training to undergo and their future was far from certain, this milestone was cause for hope.

How I became a naturalistI grew up as a city kid in Quincy, Mass. When I was 6 years old and on a summer visit to my aunt downstate in Holbrook, I came face-to-face with a creature that I’d never seen before: a garter snake. When this scaly animal uncoiled itself like an unraveling turban and moved its long body deeper into my aunt’s woodpile without the aid of legs, I may as well have been discovering a new life form. And when it slipped back into the stack of firewood as quickly as it had appeared, I panicked.

I picked up the heavy logs and heaved them behind me until the layer of mud and detritus beneath was within reach. And there, amid the spiderwebs and abandoned cocoons, was my new friend. With no preconceived notions to guide me, I reached out and gently grabbed hold of its coiled lower body. And it did the same, gliding over my wrist and “grabbing” onto my forearm with its upper body. Scared and exhilarated at the same time, I proudly took it inside, where, naturally, my aunt was less enthusiastic about my discovery.

“Get rid of it!” she screamed.

“No!” I shouted.

“Why?!”

There I was, a trembling, 3-foot-tall city boy utterly ignorant about the wild animal that was wrapped around my arm and inspiring such fear in my aunt. But I answered without hesitation.

“Because I love it!”

Somehow, amid the mayhem, she pried the snake off my arm and we put it back in the yard.

That was the day I became a naturalist. That was the defining moment when the light came on and I knew what I wanted to do with my life. For the next two years, I kept tabs on that snake as she lived her life. I learned about love and passion and birth and predation from her. Eventually, I wouldn’t need to capture her to get an up-close look — I respected her space and she stopped fleeing at the sight of me. Snakes are creatures of habit, and at some point, she apparently accepted this little boy’s presence as routine.

How I became a conservationistOne day, as I watched her bask in the sun 4 feet from where I lay on my belly with my chin resting in my hands, I saw a sharp flash of metal and heard a sickening thud. The next thing I knew, she had been ripped in two, each half of her body flying in opposite directions as she helplessly bit at the air. As the pieces of her hit the ground, they writhed like the severed locks of a Medusa, her agony not quite over. When I looked up from the carnage, I saw the man who lived next door, shovel in hand and a stern, satisfied look on his face.

That was the day I became a conservationist.

Today, I’m a conservationist because I believe that my species doesn’t have the right or option to determine the fate of other species, even ones that inspire fear in us. With 3,246 of the world’s animal species classified as critically endangered, these animals need all the friends they can get. And whether we realize it or not, we need them. The biodiversity that results when millions of species share a planet benefits our species in ways that are easy to take for granted. We’re inextricably bound with nature. When we put the survival of the natural world in jeopardy, we simultaneously put our survival in jeopardy.

As I write this introduction, with my daughter Maya’s melodious laughter drifting down the hallway to my office and her baby sister, Marina, snuggled warmly in her crib, I lament the potential loss of 3,246 species of animals they may never see. I’m painfully aware that the world they will inherit may be in a state of ecological catastrophe. It is my hope that this book will serve as a catalyst, educating people about the state of our natural world and compelling them to help protect it for future generations. We have the chance to do it, and we can succeed. Every heartbeat matters.