Memoirs and biographies make up about half of our nonfiction roundup this season. Some feel too much ink already has been used to recount the story of Laci and Scott Peterson, but it's hard to resent a book by Laci's grieving mother, Sharon Rocha. "Rent" star Anthony Rapp's memoir, "Without You," involves grief as well, as he watches cancer claim his beloved mother. On the lighter side, Diablo Cody writes about her days as a Minneapolis stripper, and Suzanne Hansen spills the beans about life as a Hollywood nanny.

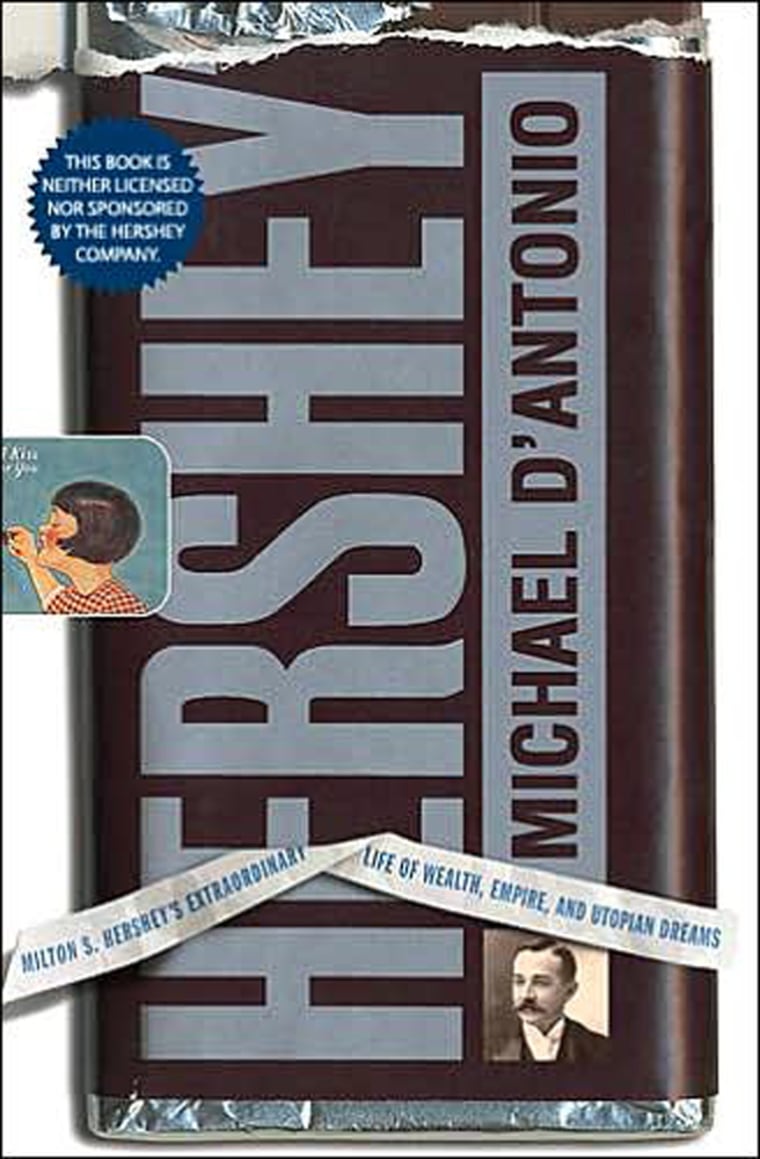

Other nonfiction this season runs the gamut. Chocolatier Milton S. Hershey's life and times are unwrapped in the amazingly thorough "Hershey." America's agony in the days of the 1930s Dust Bowl is remembered in "The Worst Hard Time." Nancy Klein Maguire takes readers inside the private walls of a monastery. Medical student Shannon Moffett examines "the Three-Pound Enigma" that is the human brain, and Portland lawyer Bill Merritt tells a rollicking crime tale that's more absurd than agonizing. —Gael Fashingbauer Cooper

Seasons of loveThree levels of readers will all take different things away from Anthony Rapp's "Without You: A Memoir of Love, Loss, and the Musical 'Rent' " (Simon & Schuster, $25). Rentheads, the devoted fans who know every note of every song, will adore the book, of course. They'll get the most out of Rapp's intimate knowledge of the musical's history, and will be fascinated by the information on early songs that were dropped and casting changes.

Readers who know the musical but aren't quite as devoted will still find plenty to hold them. "Rent" has a well-known history: Creator Jonathan Larson died on the final night of dress rehearsal. Rapp's insider tale of how Larson's loss sent shockwaves through the show, and his touching recollection of a special performance given for Larson's family and friends just after his death is chill-inducing.

Those who don't know "Rent" at all probably won't be picking up this book at all, but they'd find something in it too. As Rapp is rising to fame starring in a musical about love and loss, he's facing the biggest loss of his own life as his beloved mother, Mary, is dying of cancer. Anyone who's dealt with disease and loss will see themselves in Rapp's desperate attempts to beat back time. At points the book can get too diary-like, especially when Rapp recounts the details of his dating life. But when the story returns to his relationship with his mom, the emotion makes the book both hard to continue reading and impossible to put down. "No day like today," indeed. —G.F.C.

A daughter rememberedIn 2002, Sharon Rocha was an ordinary California mom looking forward to her daughter's first baby when son-in-law Scott Peterson called her to report that Laci was "missing." Since then, she has never awoken from the horrible nightmare she chronicles in "For Laci: A Mother's Story of Love, Loss and Justice" (Crown, $26).

Say what you will about the attention the media overpoured onto the Peterson case, the chilling facts of the murder are just as horrifying today. Laci Peterson was seven months pregnant, she was killed by her own husband, on or around Christmas Eve, and Scott Peterson went on to lie, lie, lie about everything from his fidelity to his hair color — publicly and shockingly.

Those who followed the case may not learn anything new from "For Laci," but it indeed serves two purposes. It may offer some comfort to others who are grieving, as Rocha reiterates how she found solace in the support of others and small signs — such as ladybug and dragonfly sightings — that she believes Laci sent her. And if anyone out there is still hoisting the "Scott Was Framed" flag, they need to read about how he treated his mother-in-law — ducking her calls, changing his story, refusing to let her claim some of her daughter's belongings.

There are already plenty of books on the Peterson case (Catherine Crier's is exceptional), but Rocha was forced by cruel necessity to have a very intimate take on things. Her book is better-written than readers have a right to expect from a victim's family member, and she does her daughter proud by providing the voice Laci Peterson was denied. —G.F.C.

Dust in the windAs the generations that survived it slip away, America's collective memory of the 1930s Dust Bowl has faded; unlike the Great Depression, it's all but slipped from popular consciousness. Timothy Egan's "The Worst Hard Time: The Untold Story of Those Who Survived The Great American Dust Bowl" (Houghton Mifflin, $28) paints a vivid picture that sounds like something out of a horror film.

One woman wakes in the morning to find her white pillowcase colored completely brown from dust, except for the outline of her head. The dust builds up in the lungs of babies, who die of "dust pneumonia." Even inside a farmhouse, men cannot see their own fingers. The storms are unpredictable and unstoppable, and it must have seemed like the end of the world was indeed nigh. Egan explains the actual cause of the storms; due to overzealous stripping of the land, the ruined topsoil could no longer cling to the earth. He mixes the science behind the disaster with a look at the government's scramble to decipher what was happening to the plains, and what could be done about it.

That's all good information clearly presented, but read this book for the personal stories. Egan tells of a young mother's desperate fight to keep her infant alive; of a Texan who forms a "Last Man Club," vowing to never leave the plains no matter how deeply the dust may bury him. The book's cover is eerily evocative of its contents: A translucent jacket depicts the billowing clouds of dust, while the hardback cover itself pictures two hard-bitten farmers, all but invisible behind the rolling, surging fury. —G.F.C.

Behind the baby carriage

As a culture, we’ve become inured to the obnoxious behavior of the rich and famous. But their clueless extremes still make for juicy reading, and Suzanne Hansen’s “You’ll Never Nanny In This Town Again: The True Adventures of a Hollywood Nanny” (Crown, $22) serves up steaming dish on some of Tinseltown’s most ridiculous parents.

Hansen, just nineteen when she moved to Los Angeles to seek her fortune as a child-care provider, didn’t even know who superagent Michael Ovitz was when she arrived, but she soon learned what he wasn’t: an involved or caring father. Hansen’s stint in the Ovitz household sounds like a nightmare, but it’s a fun, fast read. Her prose is accessible, hilarious and sharp, and her story confirms what we all want to believe about the Ovitzes of the world—that they’re miserably dysfunctional prisoners of their possessions who have forgotten how to treat other people (the sequence involving the household’s “Picasso alarm” is inspired).

Hansen is at her best when she’s doing shtick about the weird cheapness of the super-rich or describing, with dry horror, the sight of Sydney Pollack in a purple Speedo. Later sections covering her work for more humane celebs, and her inner conflicts about the job itself, move more slowly, but overall, it’s a warm-hearted look into two years in the life of (as Judy Ovitz charmlessly called them) “the help.” —Sarah D. Bunting

The naked truthDiablo Cody notes early in “Candy Girl: A Year In The Life Of An Unlikely Stripper” (Gotham, $24) that Minnesota doesn’t seem like a stripping kind of place. Nevertheless, when she moved to Minneapolis at 24, that’s what she decided to do. In an intriguing memoir, she takes the wraps off her experience.

The book is at its best when Cody details a life few people ever experience: how the finances worked, how men treated her, what kinds of women she met, and a host of other things you may never know you were curious about until she tells you. Of course, she also delves into the psychology of sex workers, and it is here that the book occasionally rings false. She’s generally defensive about anyone assuming that something psychological might lead a woman to strip rather than, say, become a dental hygienist. To her, this was a job, not a pathology.

But her own descriptions of how angry she came to feel about stripping suggest more complexity, as does the fact that she herself went from stripping to working in one-on-one peep shows to being a phone-sex operator. There’s a lot going on that Cody isn’t talking about, but as a travelogue through territory that’s unfamiliar to most, it works. —Linda Holmes

Good as ‘Gold’

If you’re a light drinker, $24 would probably buy you enough alcohol at an Oregon dive to get a lawyer sauced enough to tell you about some of his zaniest, wildest cases. It’s also the price of “A Fool’s Gold” ($24, Bloomsbury) a funny book by former Portland lawyer Bill Merritt that has the comfortable, rambling feel of a tale told over whiskeys.

The true-life crime story begins with young attorney Merritt inheriting a stack of cases from the recently deceased owner of his law firm, a dodgy mentor who leaves behind jewelry of questionable origins, a safe full of twenties and a staff of misfits. The cases, including the possession trial of a hippie pot queen and an ongoing state fight against an eccentric beachcombing treasure hunter, tie together in ways the young Merritt couldn’t have imagined.

Merritt has a knack for absurdist detail. A pawn shop is called “The Happy Hocker”; a secret legal award given to an honored attorney is so secret that he asks readers to “Pretend you didn’t read this.” And though most of the story takes place 20 years ago, Merritt’s grasp of Oregon’s history and the loopy hilarity of some of its residents gives “A Fool’s Gold” a strong sense of place. Unfortunately, the narrative slips out of the author’s grasp as promising characters fall out of the story and new ones appear to lesser effect. Still, there are more clever moments than not in Merritt’s book, a memoir of off-the-books legal maneuvering that’s as wayward and tangled as the Oregon coastline. —Omar L. Gallaga

No brainerA Chicago surgeon delicately plucks a bullet from a patient’s open skull. In a university lab, brains are scanned with a magnet so strong that the operating technicians can’t wear jewelry. A video game inspires a sleep study after Tetris-obsessed college students dream about falling blocks. In “The Three-Pound Enigma: the Human Brain and the Quest to Unlock Its Mysteries” (Algonquin Books, $25), medical student Shannon Moffett shines a light on our gray matter as she spends time with today’s brain pioneers.

An intro neurobiology course at Stanford sparked the author’s curiosity about current brain discoveries; likewise, the wide-eyed wonder of a pupil permeates her book. Moffett seems awestruck as she describes meeting the big names of neuroscience — occasionally coming off more cub reporter than qualified researcher. Still, the informal tone makes a challenging clinical subject more manageable for the reader. Moffett excels at similes: Legos, “The Shining,” fridge magnets, Jell-O and the Daytona 500 are all used to demonstrate intricate medical concepts.

“The Three-Pound Enigma” is rich with supplemental material. Illustrated segments build a timeline of the brain’s development, from conception to death; the author’s Web site provides links to many of the experiments, puzzles and illusions referenced in the book. Moffett gets even closer to the science when she volunteers as a test subject, skiing on a stationary machine and climbing into an eight-ton magnet for an MRI.

By exploring neurological advancement from different perspectives, “The Three-Pound Enigma” presents more than just synapses and neurons. It reveals a modern snapshot of the human condition, appealing to anyone who has ever wondered how the mind works — which doesn’t take a brain surgeon. —Tracy Edmondson

Sacred silence

There are still places in this world where most of us cannot trespass, and one of those is inside the walls of a monastery. Author Nancy Klein Maguire gets readers as close as is possible with "An Infinity of Little Hours" (Public Affairs Books, $26). She follows five men who, back in 1960, entered a rigorous English monastery to join the Carthusians, a Catholic order that is recognized as one of the most austere in the world. The men leave behind their everyday world of dates and dinners out and sports teams and slip into a cell, an intense schedule of daily prayer and hair shirts and fasting, a world that most of us cannot imagine choosing. As the turbulent 1960s churn around them, these men know very little of the world outside their walls.

There is a certain peace that develops from reading about this old-fashioned, simple lifestyle. Because the men so desperately want to tamp down their desire for the world and commit to stay in the order till death, even readers who don't understand their call (most of us) find themselves rooting for them. Not all of them ultimately decide to stay, and near the end of the book, the author talks to the men today to learn what they think of their decisions, decades after making them.

This is not a book for everyone. The religious terminology can be rough slogging even for the devout, and the book's events are quiet ones, not earth-shattering — one candidate has nightmares about not being able to keep the others on pitch in choir. Yet Klein Maguire, herself married to a former Carthusian, does an incredible job of taking readers inside this sanctuary where women are not even allowed. The level of detail is astonishing, and the book does what all great nonfiction does, paints a picture of a world with strokes so well-defined one feels as if he or she has visited it. Reading "An Infinity of Little Hours" is almost like praying. —G.F.C.

Sweet dreamsIf you're looking for a light, sugar-sparked nonfiction book about confectionery, try Steve Almond's wonderfully humorous "Candy Freak." But for a more serious look at the role chocolate played in America's history, unwrap Michael D'Antonio's "Hershey: Milton S. Hershey's Extraordinary Life of Wealth, Empire, and Utopian Dreams" (Simon & Schuster, $25).

Hershey's personal story is as rich as a fudge-filled truffle. He grew up poor and built his chocolate empire through hard work and sheer will. He was devoted to his wife Catherine, but the two were unable to have children and she died young, perhaps of syphillis. He had big dreams for the Pennsylvania company town he founded, Hershey (thankfully a contest-winning name, Hersheykoko, was scrapped). But not everything was sweet there, either: A sit-down strike in 1937 led to a bloody riot.

Hershey's life and that of the company he founded have much to teach interested readers about the history of America and the founding of businesses back in the time when it truly seemed that one good corporation could change the world. No question that D'Antonio, who shared in a Pulitzer Prize at Newsday, is an ace reporter. But for a book drenched in chocolate, entertaining anecdotes are few and far between. Probably the most intriguing tasty tidbit explains why Europeans so often shun Hershey chocolate whereas most Americans raised on it adore it: Hershey's formula for mass-producing milk chocolate quickly introduces a single sour note. A few more tasty factoids like that would have sweetened the pot, but "Hershey" is still worthy of unwrapping. —G.F.C.

Gael Fashingbauer Cooper is MSNBC.com's Books Editor. Sarah D. Bunting is a writer in Brooklyn. Linda Holmes is a writer in Bloomington, Minn. Omar L. Gallaga is a writer in Austin, Tex. Tracy Edmondson is a writer in Dallas.