I’ll never forget the first 15 minutes of my first trip to Action Park as a kid.

My younger brother and I were mulling over which ride to try first when I saw a guy who looked to be in his 20s with a feathered mullet turn and show his friend the back of his leg.

“Is it bad?” he asked.

The guy’s leg had a giant, oozing, red burn that made your skin sting just looking at it.

His friend laughed and said, “Not as bad as this!”

Then he yanked the side of his mouth open to reveal a bloody space where one of his teeth used to be.

It was as though the summertime gods were telling me, Welcome to Action Park, kid. This ain't Disneyland.

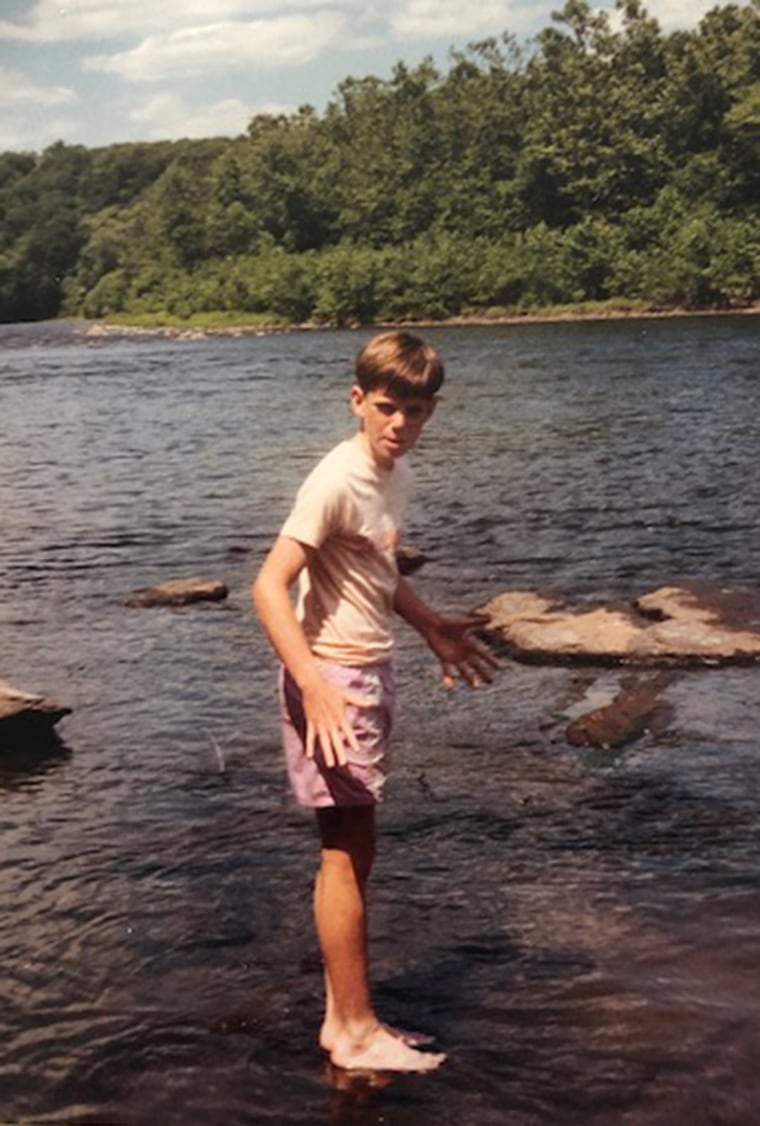

For about a half-dozen years, starting when I was 11, my family, friends and I regularly made summertime pilgrimages to the park.

Action Park's wild history has been well-documented; it has been the subject of magazine articles, a book by the late park owner's son, a documentary short, and it served as the inspiration for a 2018 Johnny Knoxville movie, "Action Point."

It has received renewed attention thanks to a new movie, “Class Action Park," which is currently on HBO Max. Watching it was like taking a nostalgia trip back to the black-and-blue — but undeniably thrilling — summers of my childhood.

In a statement to TODAY, Andy Mulvihill, the son of late park founder Eugene Mulvihill, took issue with the HBO movie, saying it was "full of inaccuracies."

"If you want the real story of what happened read my book ... and ask the millions of customers who loved the place and came back summer after summer for 20 years. They are the true unbiased judges."

As an 11-year-old in 1987, I had no idea about the park's wild reputation. Founded in 1978, it was located in the rural town of Vernon, about an hour and a half west of New York City.

Even back then, it was known as “Traction Park” (and, yes, “Class Action Park”), from the injury lawsuits that were rumored to have been filed. (A 2018 oral history of the park reported that when the park closed in 1997, it owed $3.8 million as a result of lawsuits.)

I was just excited because we had driven almost two hours from my home on the Jersey Shore to finally go to the place where, as the local commercials blared, “The action never stops!”

That combination of real terror and exhilaration made it like no other park I’ve ever attended.

During that first visit, all of the initial euphoria quickly evaporated when I saw the Alpine Slide, the ride Mr. Mullet and his toothless pal were exiting when I entered.

In the 2013 documentary short, one former visitor describes it as "a giant track to rip people's skin off disguised as a children's ride."

Sure. But I was even more scared of enduring one of the worst taunts in an 11-year-old’s world: “What are you, chicken?”

The park was actually a ski resort during the winter, so there was a ski lift that took you up the mountain to reach the top of the Alpine Slide. Once you got to the top, there was no turning back. There was only one way down.

“I heard a dude died on this ride,” someone in line would say, and your heart would start hammering.

The proper attire to protect your legs on that ride might have been leather motorcycle chaps and a helmet. But because it was 90 degrees out (and we were at a water park) everyone was wearing bathing suits and shorts. But there was no water. Just a small rectangular cart and a long, winding, concrete track.

On my first ride, the Alpine Slide started off without any issues before gravity started to do its job and I began to pick up steam. That’s when I learned that the brakes on my cart weren't in great shape, so I overcompensated, yanked hard on the handle and almost flew over the front onto the track.

I quickly let go and tried my best to steer as I went sailing down the rest of the course, rocketing past people sprawled out in the grass because they'd lost control. I made it to the bottom with only a small scrape on my knee, feeling like I had survived skydiving without a parachute.

Another difference between Action Park and regular amusement parks like Disney World was the ominous things you'd hear from older kids while waiting on line for various rides.

“I heard a dude died on this ride,” someone would say, and your heart would start hammering.

"My friend told me that a kid drowned in this pool," you might hear, before dipping your toe in the water.

This was well before Google, so what did we know? This was the age of the urban myth, when we thought Mikey from the Life cereal commercials had died from eating Pop Rocks and soda because our friend’s sister’s Canadian cousin said it was true. Maybe we really should be worried that someone had actually died on the Alpine Slide.

I found out years later, it tragically was true.

George Larsson Jr., 19, whose mother is interviewed in the HBO Max documentary, died on the Alpine Slide in 1980 when he was thrown off a cart and hit his head on a rock.

By the time I first visited the park in 1987, five people had died there, including two teens who drowned in the Wave Pool, according to the book "Action Park: Fast Times, Wild Rides, and the Untold Story of America’s Most Dangerous Amusement Park," by Andy Mulvihill and Jake Rossen.

There were 110 injuries at the park reported in 1985, including 45 head injuries and 10 fractures, according to the New Jersey Herald. The next summer, there were 330 injuries, according to the newspaper's tally.

Another ride that had mythic status in the danger department was the Cannonball Loop. It involved hurtling down a towering dark chute and then going around a 360-degree loop right before being launched into a pool.

It was never open in the half-dozen years that I went there, mainly because it seemed to be always under repair. Or maybe it was just too dangerous to keep open.

I'm thankful I never made it down. Mulvihill wrote in his book that someone's two front teeth were embedded in the loop after they slammed into the wall of the tube. The person who went after him then cut himself on the jutting teeth, he claimed.

There was something similar to the Cannonball Loop, however, that to this day remains one of the crazier water park rides I've ever been on. It was called Cannonball Falls, and it involved hurling down an enclosed water slide that made a sharp turn just before it spat you into the frigid mountain water.

It was so dark in there, you couldn't see. I got a few bad bruises from putting up my forearm at the last second before banging off the wall where the slide made its turn. The drop into the pool felt like it was 10 feet. You could always tell the rookies on the ride because they didn't have their bathing suits on tight, which meant they might come flying off when they hit the water.

Just as you would get your bearings in the freezing mountain water, you realized you better vacate the area immediately before another kid, or possibly drunk adult, came flying out of the chute to land right on top of you.

And yes, there were more than a few drunk adults.

This was the '80s, and the park seemingly sold beer every 10 feet. Some visitors in lines for rides were clearly a few beers deep into their day. In my years there, I saw more than a few shirtless scraps when somebody cut in front of the wrong group of people.

The attraction that may have caused the most embarrassment for people was the Tarzan Swing, which was a simple contraption. You walked out on a platform about 25 feet in the air to grab hold of a rope with a small handle. The swing took you in an arc above a man-made pool down below.

Once you jumped, the idea was to hold on until the swing reached its peak, and then let go.

Some folks couldn't hold on and immediately hit the water in a full belly flop, or face planted with a sickening thwack. People's bathing suits also occasionally fell off while they were in mid-air, or got yanked off when they hit the water. Watching people brave the swing was its own spectator sport.

There was seemingly nothing that was just a benign, low-key ride, like the tea cups at Disney World, to allow you to take a breather from all the action.

I remember once finishing up with Cannonball Falls and figuring I would take it easy by going down a slide like one you would see at a backyard pool — except it was about a 50-foot drop.

I was going so fast, I burned a quarter-sized hole in my Umbro shorts. I can still remember my mom shouting "We just bought those!" when she saw the damage.

Mulvihill's book also clued me in about the pink wristbands I used to occasionally see people wearing in the Wave Pool that had "CFS" written on them.

I thought maybe they were for buying alcohol or some kind of VIP access. But it actually stood for "Can't F-- Swim," according to a former first aid worker's account.

It was a park that you didn’t so much visit as survive. The bumps and bruises were all part of the experience, though, as Andy Mulvihill explained in the oral history of the park, it was never the intention.

"Gene (Mulvihill) didn’t ever want to see anyone hurt ... His goal was to build a participation amusement park that was very unique and super fun and where there were certain risks," Mulvihill said of his dad. "Individuals needed to be personally responsible for their behavior at the park."

Today, the site still lives on as a different park, which is unaffiliated with Mulvihills.

Looking back on that first trip, I still remember the adrenaline slowly subsiding as I inspected my battle wounds on the long car ride home. And then another feeling bloomed.

“Mom, when can we go back?”