Peering back at one's childhood can be a daunting task. That's especially true when trying to fill in gaps, answer questions and heal wounds from generations past — all while navigating life as the daughter of a Puerto Rican mother and Jewish father.

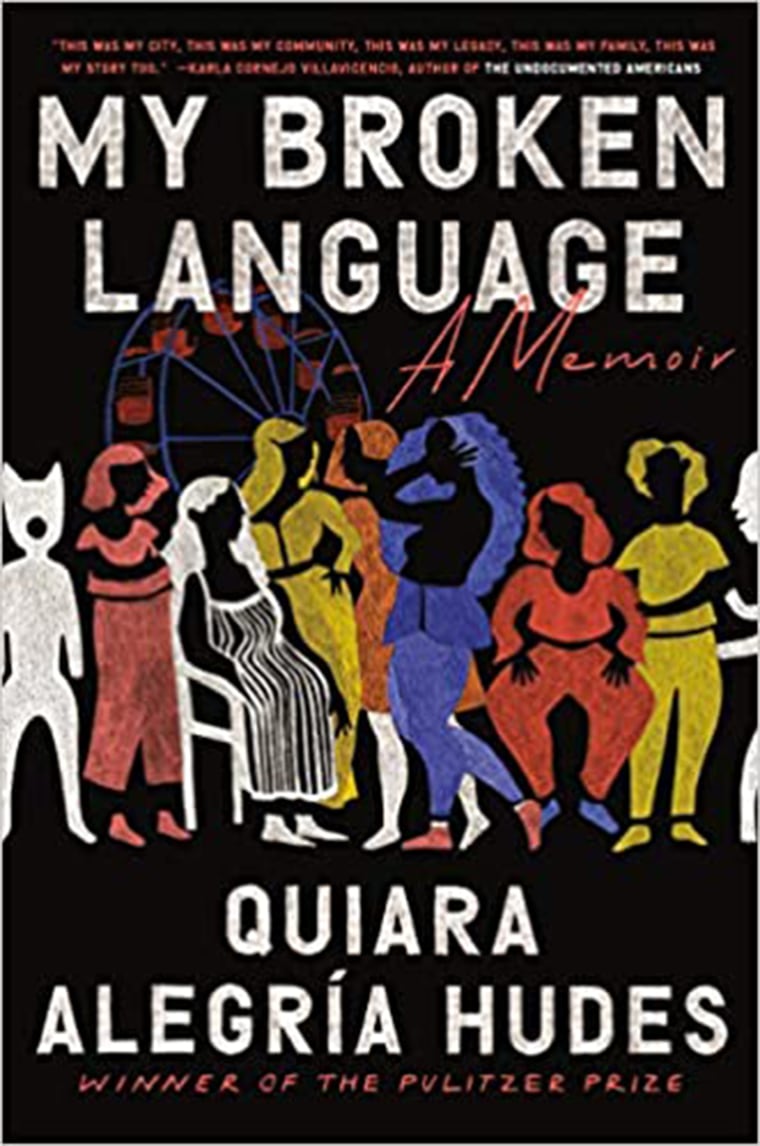

"I had to take off so much armor to sit and write this book and express, what does it mean to be half-white, what does it mean to be half-brown?" said Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright Quiara Alegría Hudes about "My Broken Language," her new memoir, out Tuesday. "What does it mean to be ashamed of my body? What's the implication if we're not ashamed of our bodies? What does it mean if I went to Yale and my older cousin is illiterate?"

It's about relinquishing the impediments of "the programs we're taught," she said in an interview with NBC News.

Hudes, who won the Pulitzer Prize in 2012 for her play "Water By the Spoonful," is responsible for introducing indelible Latina characters like Vanessa and Nina in the Tony-winning musical "In the Heights" — the anticipated movie version is coming out this summer — and Olivia and Beatriz in "Miss You Like Hell," to name a few of her multilayered characters.

They all have figments of the women from Hudes' life, but through her memoir, she shares those histories.

"This is the first time I'm dropping the pretense of fiction," she said. "Writing this book felt like a homecoming, because books mattered so much to me in my own spiritual and intellectual awakening."

Hudes said the memoir stemmed from her desire to humanize her people and community beyond their vilification by national leaders in the '80s and '90s, who "set up an entire system to destroy the lives of anyone involved in or near drugs and put a terrible moral stamp on people who needed assistance."

"My experience was quite different and reflected something that was much more beautiful and wise and lively and that reflected values that I thought this nation could learn and benefit from," said Hudes, a West Philadelphia native. "That said, it was important to acknowledge that there was tremendous suffering and tremendous struggle in my family, ranging from illiteracy to AIDS. We inherited traumas around them, and we haven't healed from all those traumas. ... The inheritances are very rich, and they're very deep, and they're beautiful, and they matter."

American identity is often defined by stories of overcoming obstacles to become successful. This story of America lies in contrast to a past vision of glory where the privileged are lauded and others are considered second-class citizens. The gap between these reflections has resulted in ever-changing standards of who is granted citizenship and whose stories are told and the inability to settle on a unified vision of what it means to be American.

Flawed languages — and that's OK

To speak English, Spanish and Spanglish, Hudes describes in the book, is to know too much and too little about language and be three times as good — and not good enough — at following the backward trail of family stories.

It was fellow Pulitzer-winning playwright Paula Vogel, Hudes said, who exhorted her to rethink loyalties to language because "language that aims towards perfection is a lie."

Hudes' languages are flawed, they're broken and that's OK. It is then that she finds some relief and offers what becomes the memoir's takeaway: You cannot always make circular stories about identity into something conclusive.

"My Broken Language" is a meditation on Latina girlhood and womanhood but also on the ways we examine intergenerational trauma, harmful relationships, addiction and immense grief. Hudes elegantly illuminates the underbelly of what we think of as representation and asks us to push against it and reflect on whom it liberates, if anyone.

This is partly because the mainstream press still has difficulty parsing artists like Hudes and the works of fiction their lives inspire. She's not buying into the fantasy of greater visibility. She just wants to heal intergenerational trauma and help future generations do the same — with hopefully more information.

"My Broken Language" and its renewed focus on reciprocity, values and teachings signals a long-overdue resurrection of sorts — a revival of the once-condemned mysticism entwined in Latino heritage.

"I'm not telling a story about a migrant family that comes from the farm and Arecibo to here to simply receive enlightenment from the United States," Hudes said, referencing a city in Puerto Rico. "I'm telling a story of a migrant family that has arrived here and has enlightenment to offer the United States, and I think that two-way street is very important."

Hudes revealed that part of her writing process and philosophy included asking herself what a woman's values are and what Puerto Rican values are.

"Those are cariño, respeto y honor [care, respect and honor] especially when dealing with elders," she said. "That's something we've struggled with as a nation this past year."

Proud of 'just how many Latinx roles I've created'

Hudes has honed this philosophy in her playwriting, approaching characters and actors like a "hiring agent" because she makes "really good jobs for excellent Latinx performers to rise to the level of their skills." It's no surprise that her stage work gives audiences more than they bargained for by challenging the notions of cultural hegemony, offering alegría de vivir — the joys of living — when white audiences expect a tale of martyrdom.

"I look back on the plays I've written, and I do the numbers on just how many Latinx roles I've created. I'm so proud," Hudes said. "I think about the actors who have filled those roles and the struggles they've had going to audition and getting rejected from playing 'drug dealer one' or 'maid No. 2.'"

What’s next for Hudes? There's, of course, the film adaptation of "In the Heights," and she doesn’t rule out writing another book. She still has grander plans and hopes, not just for herself but for a new generation of theatergoers, especially young people from diverse neighborhoods.

"We have to be concerned with getting the theater into the neighborhoods," she said. "Theater is about human bodies in space, in real time — that space gives a lot of information.”

In the time Hudes has been away from the suburban Philadelphia home she shared with her parents, she has both changed and stayed the same. Though she's now an award-winning playwright and memoirist with a family of her own, she still channels the power of reciting poems to trees and stories to ferns in the woods, as she used to do when she was a kid. The sunlight and rain transforming her mother's garden was nothing short of alchemy for young Hudes.

Hudes said she still has to think about the habits that were programmed into her mind about what makes a "proper" lead character. But she counters it by reminding herself there's power in her experiences.

"Do not let your imagination match the size of what you've seen," she said. "Write what you haven't seen told before."

This story first appeared on NBCNews.com.