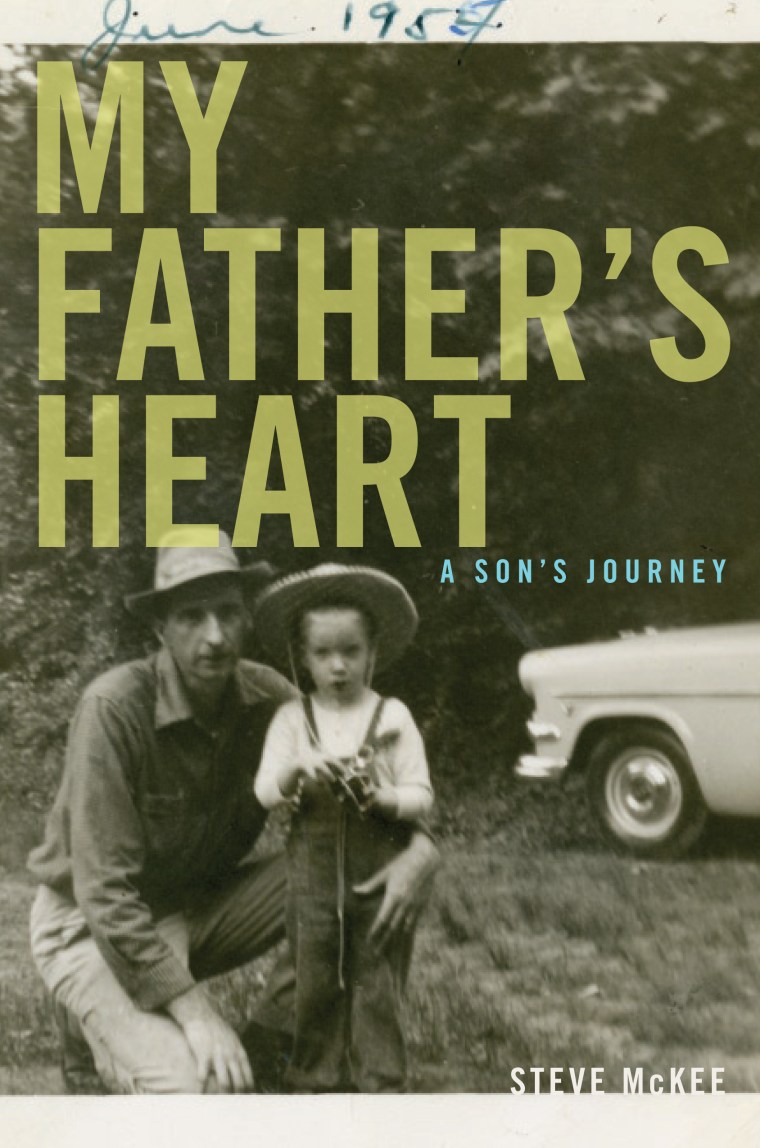

From Steve McKee comes “My Father's Heart,” a memoir of a father-and-son relationship cut short by heart attack, and the powerful pull of love across the empty years. An excerpt:

About two years before the heart attack that killed him, I had told Dad in so many words that if he didn’t clean up his act, he’d be dead in five years. Quit the smoking, get some exercise, stop nailing himself to the cross of his job. We were sitting at the kitchen table, he and Mom and I. Kathy was away at school. Dad had already had one heart attack, in 1963, when he was forty-four. It had been such an obvious warning shot across the bow. How could he not have heard it, when I so clearly had? He looked straight at me and said, “You’re right.” I wanted to reach across the table, grab him by the collar of the white dress shirt he always wore to work, and shake him. All these years later, I still do.

Shake him for proving me right with years to spare. Shake him for the cigarette cough my sister Kathy and I woke up to every morning of our lives. For missing my high school and college graduations, my wedding in 1978. For not being here for me and my wife, Noreen, to share with him the baby, Patrick, that we adopted in 1990. And for Mom, the former Helen Theresa O’Neil of Seneca Parkside, for being his widow for thirty-seven years, fifteen years longer than she was his wife.

The truth? I think Dad gave up. I do. His father, my grandfather, Jack McKee, died on July 6, 1941, of a “Probable Coronary Occlusion,” according to the death certificate. Probable is wholly unnecessary here; we are talking McKee family history, after all. For Jack, and for my Dad, it came all of a sudden, out of the blue. Jack McKee was fifty-three when he died, and Dad was twenty-two at the time. Mom says that Dad “adored his father.” As he wrote home to his mother during World War II: “I’m glad you see a resemblance between myself and dad. I’m trying, you see, to be a good man.” Jack McKee was a plasterer by trade, a staunch union man — Local #9 out of North Tonawanda. Despite his profession (though in a way because of it), he had beautiful, soft hands. The plaster dried them out terribly, so he took meticulous care. Every night, home from work and before reading the Buffalo Evening News in his rocking chair, he would sit at the kitchen table with a bottle of olive oil, kneading it into his hands and fingers. He belonged to the Buffalo Racing Pigeon Concourse, and he followed the horses, though not as a betting man. He also enjoyed the fights on the radio. What Irishman didn’t? Jimmy Slattery from the Old First Ward won the New York State version of a world light-heavyweight title in 1927 and three years later won it again, barely holding off another Buffalo boy, Lou Scozza, in a fifteen rounder right there at the Buffalo Broadway Auditorium.

My grandfather’s heart attack happened on the way back from a day at Sunset Bay, one of many Lake Erie vacation spots southeast of Buffalo. Jack was driving. Next to him was my grandmother. We grandkids would know her as “Nana.” Jack always called her “Babe.” Without warning he pulled his blue Plymouth to the side of the road. “Biddy,” he said, “how about if you drive?”

“Biddy” was Mary Jane, his eighteen-year-old daughter. As with “Babe” for his wife, only Jack could call Mary Jane “Biddy.” They were his nicknames. A thrilled Mary Jane — she had only recently gotten her license — took the keys and slipped behind the wheel. Jack, meanwhile, got in the back next to his other daughter, seventeen-year-old “Skipper.” Her real name was Alice Elizabeth.

“Jack!” That was Nana talking — screaming, really — as she turned around to look at her husband. It is impossible to know what prompted her to say it, what she’d heard, what she knew in that instant. It all happened too quickly. Mary Jane hadn’t even put the key in the ignition, and my Aunt Alice, next to her father, says she remembers hearing no sound. Maybe Nana knew something was amiss as soon as Jack pulled over and asked Mary Jane to drive. Jack always drove. Maybe after a quarter-century of marriage she just knew.

In the time it took her to turn around and scream, Jack’s head had been thrown against the seat and held there. One time only his head went back, and that’s how he stayed, unmoving. He had been to the doctor’s only days before — no reason, just a checkup — and had been declared fine.

Alice was dispatched to find a phone to call John, her older brother, my father. They had all said goodbye only about an hour earlier in front of the Sunset Bay cottage that Dad and some of his buddies from the neighborhood had rented for the summer — eight guys, $13 each for the season. Alice, the kid sister, loved having a big brother if only because it meant there were always boys at the house on Rodney Avenue or, like now, down at the lake. This time, though, there were older girls there, too, John’s age or thereabouts, from South Buffalo. They had rented a cottage a street or two away — with two live-in chaperones, of course.

So there had been many people to say goodbye to, some of whom the McKees had just said hello to for the first time. That included a twenty-year-old Helen O’Neil — Mom — from South Buffalo in the city’s longtime Irish belly. Indeed, it had likely been Nana’s desire to meet this girl whom her son had been going on about for three years now — “Mom,” he’d been telling her, “she laughs at my jokes!” — that had brought the McKees down to Sunset Bay in the first place, after an early Sunday Mass at Blessed Trinity Church. Nana having now taken her measure, the McKees had then headed home. Dad, meanwhile, rode back with some of the guys from the lake.

By the time Alice got to a phone, hours had passed since that parting. Dad was already at the house on Rodney Avenue, a nondescript street hard by a quarry on Buffalo’s East Side. He was already in bed, up in the third-floor attic that as a kid he had shared with his older brother, Tom. Weekends at the lake were surely filled with lots of Utica Club beer and plenty of laughs but not much sleep. Monday morning and another day at Trico Products, where he worked in the traffic department, would dawn soon enough. When Alice rang the phone on the parlor floor — Parkside 5739 — it went unanswered. Eventually she got ahold of Walter Doersam from across the street. He climbed the back stairs to the attic. Together the two drove back, looking for Jack’s Plymouth. They found it, near Southwestern Boulevard and Camp Road in Hamburg. There was a lumpy white sheet spread out on the ground next to the car.

It was a solemn ride to Rodney Avenue that night. In five months plus a day Pearl Harbor would be attacked. For everyone in America the old world would be gone. The McKees in the blue Plymouth merely got a head start on the great upheaval. With Jack gone, so was “Biddy” and so was “Skipper.” Only he could call them that. When they had been little and Nana would be off with her lady friends for a Saturday afternoon’s shopping, Jack would often scrub the kitchen floor. He would sit his two girls on the kitchen table and give each a glass of water. When he needed to raise more suds in a particular spot, he would point to it, and Biddy and Skipper would take a drink, aim, and spit. Now all that gone.

Gone too was my father’s nickname. Jack McKee called his second son “Steve.” And, of course, only he could. I never learned where “Steve” had come from; I don’t think Dad knew, either. But Steve it was; first for Dad as a nickname, then for me as a real name.

Dad rarely talked about his father, and he never told me anything about the day he died. Once Dad had got knocked on his back by that first heart attack in 1963, I think he never quite got up again. Born on January 21, 1919, he had grown up through the Depression, been a young man in World War II, and had been a married man with a family in the postwar boom. He’d worshiped in the church of the American Dream, a true believer in the up-by-your-bootstraps gospel. And he reaped what he sowed, in an unassuming, middle-class sort of way, fine by him. I think he came to see a price to be paid for all that, and so be it.

For the six-plus years between Dad’s two heart attacks, we McKees lived in a surreal sort of suspended animation, treading carefully, wondering if — when? — the other shoe would drop, another coronary artery clog. He was forty-four when he had his first attack on February 2; mom was forty-two. My sister, Kathy, was in eighth grade; I was in fifth. Dad spent at least a month in York Hospital, most of the time flat on his back, for weeks not permitted even to lift his arms above his head. He spent six more weeks at home before going back to work as a traffic-management executive at Cole Steel Equipment, the office-furniture company that he had worked for in York since 1954. “The boss of the warehouse,” as Kathy and I liked to say.

Dad back to work! Yes, that was the ticket, the “normal” to which we all aspired. And that’s what we got, with a vengeance. Dad loved what he did for a living. But he hated his job. The stress, the boss — one was the other, and he handled neither well. It all conspired to kill him; never will I think otherwise.

Returning Dad to work meant that Dad returned to cigarettes. Couldn’t we see that coming? He started up again within months after getting back to his office on the second floor, with the wall of windows looking down on his warehouse of responsibility. It was during that period, between his attacks, when I first started running.

***

In 1968, Dr. Kenneth H. Cooper published Aerobics, a seminal tract on the benefits of exercise. I can still see the book on Mom’s Early American dough-box end table in our living room. I had placed it there conspicuously in the hope that Dad would see it, read it, and get out the door himself. So yes, there was something out there warming up, stretching out, getting ready. I could feel it with every stride. Or at least I wanted to, desperately at that. I wanted Dad out there with me crunching the cinders — him and me, shoulder to shoulder. “Steve” and Steve facing up to our shared legacy while simultaneously facing it down. He had been a hunter and a fisherman all his life, but increasingly he was allowing his work to keep him from the fields and streams. I wanted him to stop smoking, eat right, quit his job. I wanted him to take charge. To get in shape, be in shape, stay in shape. He never did.

So I did it for him, and I have been doing it ever since. College basketball. Rec league hoops and volleyball. Cross-country skiing. A bicycle as primary transportation. In 1980, I returned to regular, daily running, ran a marathon, and then continued to pound out the miles until I was past forty, when the knees finally screamed in protest. I turned to a rowing machine, my 6-foot-8-inch frame well suited to the push and pull. I started lifting weights. I did nearly two years of low-impact aerobics, spent a few years ice skating, one summer swimming. I bought another bicycle. And on “off” days I walked to work at the Wall Street Journal in lower Manhattan, fifty minutes over the Brooklyn Bridge from our house across the East River.

Never not in shape; always the secret.

In 1990 my wife, Noreen, and I adopted a baby boy, Patrick. We were in the birthing room with his birth mother. The delivery was difficult. The ordeal left Patrick exhausted, unable even to cry for almost thirty-six hours. But when I held him in my arms for the first time and looked down at his little white stocking cap, my past, present, and future collided. Never again would I be just that sixteen-year-old kid at the junior high track trying to get his Dad in shape. I would be the father Dad never was, staying in shape for his son.

I brought all of this with me to an “executive physical” at a clinic in New Jersey on Tax Day 2005. All of it — Dad, Patrick, the last day of my father’s life, the first day of my son’s. This eight hours of treadmill test, nutritional assessment, and full-body scan was not my idea. I was fifty-two years old, in shape, always had been, so what was the point? But Noreen insisted.

Once there I warmed to the task, and by the end of the day I was fairly giddy with success, ready for my Olympic gold medal, Munich 1972. Coming off the treadmill test, I was even dressed for the victory platform, in baggy sweats. I could have been running the junior high track right then. But instead I was sitting in another office with another wooden desk, now across from a cardiologist. He was affable, friendly, enthusiastic; his confidence in the technology at his disposal was unshakable. This was the second time we had talked today. Earlier, in a lengthy conversation, I had told him my story. Now he was telling me his, or at least that part about what all these various tests could reveal. He was in the business of collecting data, which could then be put to work.

Seamlessly, he turned my attention to one of the two computers on his desk. On the screen were a series of digital slides, all in shades of black and gray. Then suddenly, there it was, a blotch of white, stark in its contrast. The doctor said nothing. He didn’t have to. The blockage was in about 20 percent of my left anterior descending artery. There was about the same in my right coronary artery. My risk of having a heart attack within the next twelve months: 10 percent or more, according to the data. Left untreated, the risk would only compound, making a heart attack a near certainty.

This was going to take some getting used to.

Excerpted from “My Father’s Heart: A Son’s Journey” by Steve McKee. Copyright 2008. Da Capo Lifelong Books. All rights reserved.