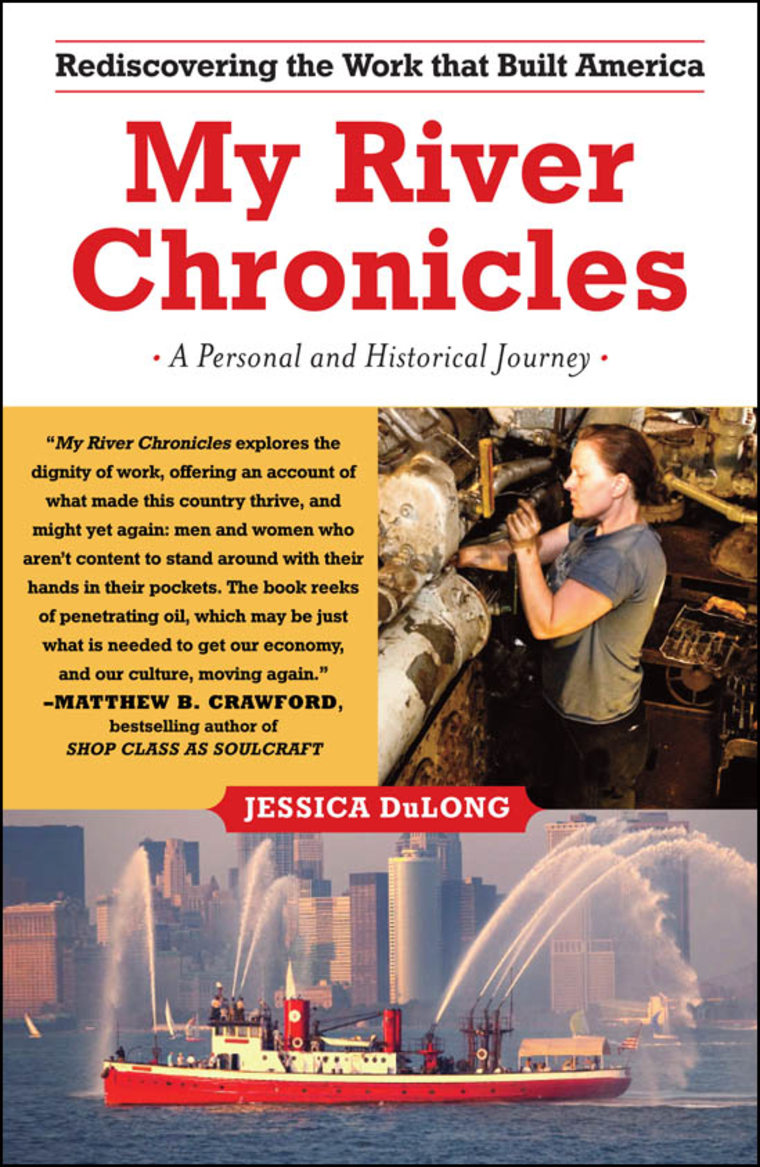

Jessica DuLong, a graduate of Stanford University, accepted a serendipitous invitation and discovered a whole new world of work. She volunteered aboard a retired New York City fireboat and then spent the next 10 years learning the complex machinery that was built decades before the advent of computers. As she joined the restoration team, she discovered a newfound passion for hands-on work. An excerpt.

Chapter Two: Girl Meets Boat

On my first day at the fireboat controls, I have an audience of men. Never before has a woman run these engines. The pedestal was designed for someone six feet tall, and I’m five-foot-five, so the leverage is all wrong. Whenever the captain, Bob Lenney, signals Full Ahead, I need two hands to move the control lever into position, and have to stand on my toes to swing the telegraph pointer all the way up.

Props at 100 rpm for slow, 200 for half, 300-plus for full. Huntley Gill threw all these numbers at me in a five-minute rundown, his cavalier tone only exacerbating my nervousness. He was the one who had offered me the chance to try my hand at engineering. “I don’t know anything,” I’d said, offering him the chance to back out.

“You don’t have to,” he’d replied. “A trained monkey could do it.” Don’t let the amps climb past 1,350. Run each engine at eleven-hundred. “All set?” Huntley asked, then headed back up the stairs, leaving me alone at the stand.

On a bell boat like this one, the pilot can’t directly control the propellers, so he signals down to the engine room from where he stands in the wheelhouse. Today the movement of the propellers will depend on me. I have to read the commands, then shift the levers that move the boat and regulate its speed, in a harbor full of other vessels.

As I stand searching for answers in the gauges, sucking in short, tight breaths, the sun stops spilling down the stairs for a split second. I turn around and watch a pair of work boots begin their descent. It’s Tim Ivory, the supervisor and mastermind of the boat’s restoration, who’s also in charge of everyday operations.

With an unsmiling nod, Tim heads toward the back, and I hear the chug of an engine trying to catch. Then another. Each hrumph rumbles in my chest. I stand in one spot, hands limp at my sides. How did I get here? I wonder as the space roars to life. When Tim returns, I wave him over, leaning in toward his muffed ear and yelling, “I don’t know how to pump water.”

“That’s later,” Tim snorts. “You think we’d just leave you down here by yourself?”

“Uh…no?” I stammer, my shoulders tight, the soles of my feet tingling, semi-numb from being planted so firmly.

The engines ring out like a siren call, and a bunch of guys, one wielding a video camera, come down the stairs to watch me pull the boat off the dock. Sweat pools, sticky where the plastic earmuffs rest on my cheeks, beading up and running over my temples, trickling off my jaw. I don’t dare take my hands off the prop levers to wipe away the drips. I stand at attention, my body rigid, my head full of numbers.

The first signal rings down: Slow Ahead. I lean my weight into the brass lever and it click-clicks stiffly forward. I watch the needle on the propeller gauge, and when it creeps past one hundred—too fast—my heart lurches and I yank the lever back. I don’t look at the faces around me. I convince myself that the video camera is just another set of eyes.

Another clang from the wheelhouse. Slow Astern on the left side. It seems counterintuitive to go in two directions at once. I falter and Tim jumps in from behind. Without a word, he grabs the lever, folding his whole huge hand around my white knuckles, and jerks it into position. “Sorry,” I mouth. He steps back and I feel the blood rush in my head. Some monkey.

But at the end of the trip, I share beers with the crew and the pilot, Bob, shakes my hand. “Very responsive,” he says, which means everything coming from this man of few words.

The glass bottle in my hand drips condensate onto the steel deck as I hang quietly in the background, listening to the boat banter. This is the first of many nights I will find myself skipping city cocktails in favor of beers on the boat to hear the salts swap stories.

Excerpted from "My River Chronicles: rediscovering America on the Hudson" by Jessica Dulong. Copyright © 2009 by Jessica Dulong. Excerpted with permission by Free Press, a Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.