Twice now, Todd Bridges has reached out to fellow former child stars-turned-addicts to try to get them to stop destroying their own lives. And both times his efforts were in vain.

The former star of “Diff’rent Strokes” told TODAY’s Meredith Vieira Monday in New York that about a year ago, he talked to Corey Haim about his drug use.

“I had tried to get Corey to stop taking prescription drugs and take care of his life,” Bridges said. “I tried to get him to understand that there was a different way out.”

Haim died last Wednesday at the age of 38. His death was attributed to heart failure associated with his drug use.

“He wasn’t ready to stop,” Bridges said of Haim. “The thing about drug addiction is, sometimes people are ready to stop and sometimes they’re not. You have to have it in your mind that you’re ready to stop.”

Sex and drugs

The previous time Bridges went unheeded was in 1999, when he called his old co-star on “Diff’rent Strokes,” Dana Plato, who had played the natural daughter of Philip Drummond, a rich New Yorker who adopted Willis (Bridges) and Arnold Jackson (played by Gary Coleman), two poor black kids from Harlem.

Plato was two years older than Bridges, who was almost 13 when “Diff’rent Strokes” debuted in 1978. A precocious girl, Plato introduced Bridges to heterosexual sex as well as marijuana and alcohol.

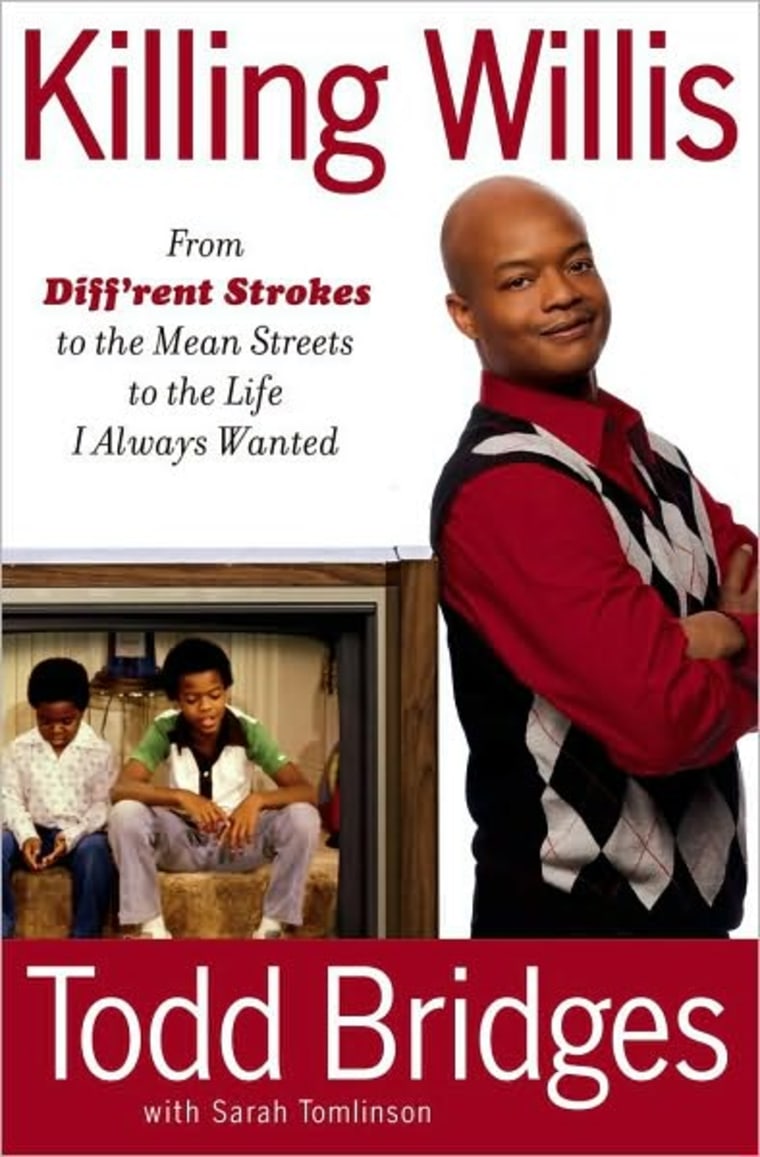

That story is retold in Bridges’ book, “Killing Willis: From Diff'rent Strokes to the Mean Streets to the Life I Always Wanted,” detailing his own harrowing descent into addictions to cocaine, crack and methamphetamines.

The drug use was his response to feelings of worthlessness, Bridges said. His father had been an unloving alcoholic who abused him and his mother mentally and physically. But his father’s worst sin, according to Bridges, was refusing to believe his own son when Bridges was sexually molested by a man who was acting as his publicist.

The molestation left Bridges with feelings of doubt about his own sexuality — doubts that Plato dispelled when she initiated a sexual affair that began when Bridges was about 14 and continued for the run of the show, which ended in 1986.

“She came at a very pivotal point in my life, where I was fighting whether or not I was homosexual or not,” Bridges told Vieira. “I didn’t know what I was. When I experienced it with her, I realized I liked women. I didn’t feel dirty.”

A call unheededBridges also talked about doing drugs with Plato, mostly on the weekends: “I was never high on the set,” he told Vieira. But, he wrote, he probably got high with Plato after work on the day that first lady Nancy Reagan, the originator of the “Just Say No” anti-drug campaign of the 1980s, appeared on the show.

“That whole ‘just say no’ didn’t really work for too many people in America,” Bridges observed.

It certainly didn’t work with him, or with Plato. But Bridges managed to clean himself up after a final arrest in 1992 and now has nearly 17 years of sobriety.

In 1999, he called Plato, who was still addicted at the age of 34. “Dana, there’s a program I can get you in,” he told her.

“I don’t have the problem like you do, Todd,” she replied.

Three days later, Plato was dead of an overdose of prescription drugs.

‘Suicide by cop’

By all rights, Bridges admitted, he should be dead too.

In 1992, he came within a heartbeat of committing “suicide by cop” when he was pulled over by police after making a drug buy for a girlfriend. With a policeman at the window of the car, Bridges planned his next move: He would reach for the gun he had in the glove box and point it at the cop, who would then put Bridges out of his misery.

“I hated myself. I really hated myself. I couldn’t stand who I was,” he told Vieira. But before he could act, “I heard this voice tell me that it wasn’t the right move, that literally not to do that and to give myself a second chance to really find some happiness.”

By then, Bridges had been in prison for nine months on charges of murdering another drug dealer. Defended by Johnnie Cochran, he was found not guilty in the trial, but he had several other run-ins with the law. He was a drug dealer and an addict.

When he finally sobered up, he said, it was very difficult getting back into acting, the profession he had fallen in love with as a 5-year-old watching “Sanford and Son.”

“I think there is a racial divide in the industry that makes it much harder for blacks to get a second chance,” Bridges wrote. He says he finds that, despite his 17 years of sobriety, the media treats his addictions as if they just ended. “I’m not saying that it’s racist, I’m not saying that it’s wrong, but it’s happening to me,” he added to Vieira.

Bridges is married with two children, a 13-year-old daughter and an 11-year-old son who wants to be an actor, too. He travels the country speaking about addiction and still works in movies and television, most lately as a host on Tru-TV’s “World’s Dumbest Criminals.”

If there is a lesson in his life, said Bridges, it is this: “There is life after death.”