Does an internal compass dictate how dogs line up when they defecate? How do you figure that out? And why would you want to?

Such are the questions you get into when addressing the weirdest subjects of scientific research.

"If something's not familiar to you, it's going to seem weird. But a big part of a scientist's job is to study and make sense of what's not familiar. They focus your attention on it, and you think, 'Whoa, that's really interesting!' At that moment, 'weird' and 'interesting' are exactly the same thing," said Marc Abrahams, who collects weird science as the editor of the Annals of Improbable Research and the impresario behind the annual Ig Nobel Prizes.

Abrahams is due to discuss the philosophy behind science that makes you laugh, and then makes you think, during Friday’s edition of "Virtually Speaking Science." The hourlong talk show, hosted by yours truly, airs at 8 p.m. ET Friday on BlogTalkRadio and in the Second Life virtual world.

This show celebrates the Ig Nobels and our own Weird Science Awards, plus the latest in offbeat research — such as that study on doo-doo directionality. The paper, published online in a peer-reviewed journal titled Frontiers in Zoology, was featured this week on Abrahams' website, Improbable.com. It could end up as a future Ig Nobel and Weirdie winner.

"It certainly is a contender for a prize," Abrahams told NBC News. "because it's funny and because it gets people talking about the details — whether you're a dog lover, a dog hater, or possibly a dog."

The straight scoop

The dog-poop experiments, conducted by Czech and German researchers, built upon previous studies suggesting that cattle, deer, foxes and other types of mammals sometimes line up preferentially along Earth’s magnetic field lines. Such behavior hints at a mechanism behind the animals’ sense of direction.

The researchers reasoned that dogs should have a similar magnetic sense. They said "a discovery of magnetoreception in dogs would open totally new horizons for magnetobiological research," because dogs are already widely used in behavioral and biomedical experiments.

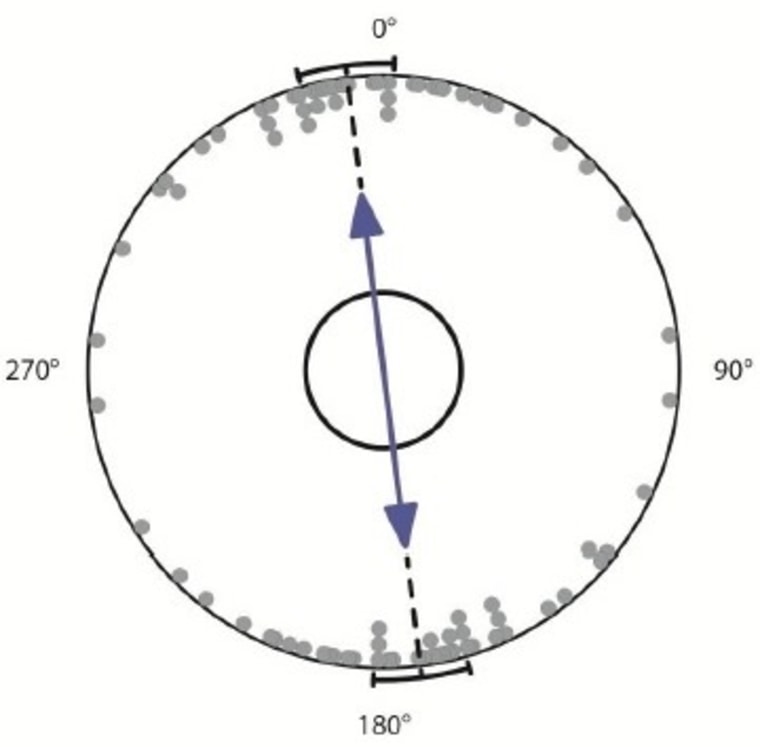

So they took 70 dogs, representing 37 different breeds, on a wide variety of outings over the course of two years — and watched how the animals lined up when they did their business. They collected directional data (and, one assumes, the dog poop) associated with 1,893 defecations and 5,582 urinations. Then they analyzed the distribution of compass directions.

At first, the distribution looked random. But then the researchers reprocessed the data, looking specifically at periods when Earth’s magnetic field was "quiet" and not knocked slightly out of alignment. When they did that, the results were more significant. The dogs favored either facing north or facing south when pooping. When it came to peeing, males preferred a northwest heading, while females stuck with the north-south axis.

Does it pass the sniff test?

The researchers dismiss alternate explanations for the dogs’ orientation — for example, that they were aligning themselves to keep the sun out of their eyes. But they confess it's not clear why the dogs lined up the way they did.

"An answer may lie in the biological meaning of the behavior: If dogs would use a visual … magnetic map to aid general orientation in space, as has been proposed for rodents, they might have the need to center/calibrate the map now and then with regard to landmarks or a magnetic reference," they write. "We might think of this the same way as a human is stopping during a hike to read a map."

Time will tell whether the researchers' claims will stand up to verification. Although the processed results sound as if they have statistical significance, that's not clear-cut. S. Rao Jammalamadaka, a statistics professor at the University of California at Santa Barbara, said in an email that the authors apparently picked subsets of data to support their hypothesis, "which doesn't seem to hold water for all the data they collected."

"The tests they performed (Rayleigh's test and Rao's spacings test — incidentally, I am that Rao who introduced that test!) only help assert that the directions are not isotropic, i.e., not uniform around the circle under these specific conditions," Jammalamadaka told NBC News. "When one takes 1,893 or 5,582 observations on 70 dogs, these are not independent data, for which such tests are meant. My unscientific observation is that a dog revisits a place and perhaps positions itself in the same way when it does it again."

Lessons learned

The doggie-doo research is a good example of how scientific claims, weird or otherwise, should be put to the sniff test.

Abrahams noted that there are usually two parts to a scientific paper. "One part is where they are telling you what they saw, and the other part almost always comes at the end, where they tell you what it means," he said. "Often, that’s the part that’s questionable. But that’s also the part that usually ends up getting passed around."

Verifying the sources of information, and assessing the interpretation of that information, are key parts of the process — not only for the ones doing the research, but for those hearing about it as well.

"It’s not just science," Abrahams said. "If your friends tell you about something while you're at coffee, you’re probably doing the same kind of detective work."

The authors of the research paper in Frontiers in Zoology, titled "Dogs Are Sensitive to Small Variations of the Earth's Magnetic Field," include Vlastimil Hart, Petra Novakova, Vladimir Hanzal, Milos Jezek, Tomas Kusta, Veronika Nemcova, Jana Adamkova, Katerina Benediktova and Jaroslav Cerveny of the Czech University of Life Sciences; and Erich Pascal Malkemper, Sabine Begall and Hynek Burda of the University of Duisburg-Essen in Germany.

Find out more about doo-doo directionality, the Ig Nobels and the Weird Science Awards (starring kinky bats!) by tuning in our talk on "Virtually Speaking Science." You'll also get some tips for your own everyday detective work. You can join the live audience at the Exploratorium’s Second Life auditorium, or tweet questions using the hashtag #AskVS. If you miss the live show, never fear: The podcast will be archived at the "Virtually Speaking Science" website and on iTunes. Check out these archived shows from "Virtually Speaking Science":

- Sean Carroll and Matt Strassler on dark matter and more

- Dave Brain on the Maven mission to Mars

- Phil Plait on detecting pseudo-scientific B.S.

- Roger Pielke Jr. on the outlook for climate policy

- Joy Crisp and Doug Turnbull on Curiosity's year on Mars

- James Oberg on Apollo 11's legacy

- SETI Institute's Seth Shostak on aliens in the movies

- Brian Switek on dinosaur fact and fiction

- George Djorgovski on the Internet and education

- Doug Griffith and Taber MacCallum on moon and Mars trips

- Sean Carroll and Matt Strassler on physics' X Files

- Ig Nobel's Marc Abrahams on weird science in 2012

- Paul Doherty on Curiosity and the year in science

- Shawn Lawrence Otto on climate change and the 2012 election

- Sean Carroll on what lies beyond the Higgs boson

- Alan Stern on the Uwingu mystery space venture

- George Djorgovski on the future of immersive virtual reality

- JPL's Dave Beaty previews Curiosity's mission on Mars

- SETI Institute's Seth Shostak about aliens and UFOs

- Paul Doherty on solar eclipses and the transit of Venus

- Veronica Ann Zabala-Aliberto on spaceflight and Yuri's Night

- JPL's Dave Beaty on the search for life on Mars

- Shawn Lawrence Otto on science and politics

- Ig Nobel impresario Marc Abrahams on silly science in 2011

- Rocket scientist Robert Zubrin on Mars exploration

- Propulsion expert Marc Millis on interstellar spaceflight

- Sean Carroll on the puzzles facing physicists

- Rand Simberg on the private-enterprise vision for spaceflight

- Martin Hoffert on the future of energy policy

- George Djorgovski on science in virtual worlds

- Alan Stern on suborbital research and NASA's mission to Pluto

- Col. "Coyote" Smith on the outlook for space solar power

- Tim Pickens on rocket ventures and the Google Lunar X Prize

Alan Boyle is NBCNews.com's science editor. Connect with the Cosmic Log community by "liking" the NBC News Science Facebook page, following @b0yle on Twitter and adding +Alan Boyle to your Google+ circles. You can also check out "The Case for Pluto," my book about the controversial dwarf planet and the search for new worlds.