Nicole Hockley lost her 6-year-old son, Dylan, in the 2012 mass shooting at Sandy Hook School in Newtown, Connecticut. Very quickly, Hockley learned there had been multiple signs and signals from her son's killer that could have led to preventing the tragedy if they had led to interventions before he walked into the elementary school that morning.

"It's too late to save Dylan, but if the lessons that we have learned can help someone else save a life, then we are going to keep doing what we can to make that happen," Hockley told TODAY Parents.

To that end, she co-founded Sandy Hook Promise, an organization that focuses largely on preventing violence. Next week, the group will host Say Something Week in the hopes of encouraging schools and organizations across the country to teach their students and parents how to prevent similar tragedies from occurring in their own communities.

According to Sandy Hook Promise, research over the past 25 years has shown that in 7 out of 10 acts of gun violence, the shooter had told at least one person that they might commit an act of violence ahead of time. One study found that an attacker revealed their plans ahead of time in 4 out of 5 school shootings.

Never miss a parenting story with TODAY’s newsletters! Sign up here

"What happened at Sandy Hook was not a unique event," Hockley said. "A lot of these acts of violence follow a certain timeline of events and include signals that no one recognizes."

The problem, she said, is creating mass awareness. "This is something that we need to do," said Hockley. "We can reach kids, parents, and teachers and show them what the signs and signals look like as well as what to do when they see them."

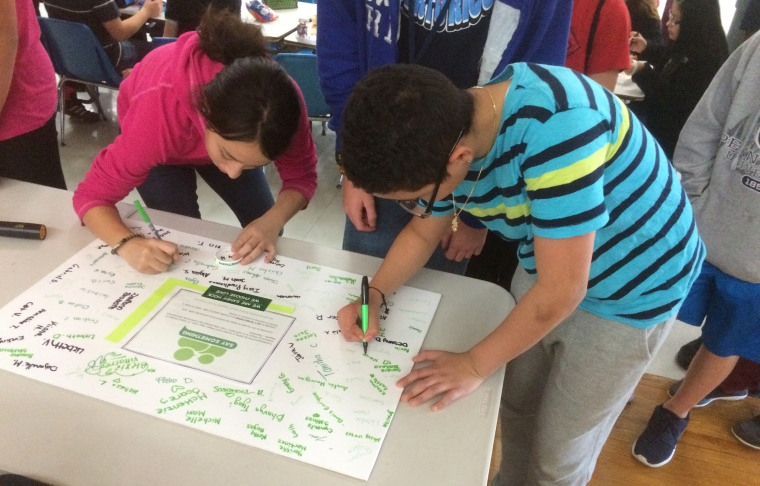

Sandy Hook Promise has created the Say Something curriculum to do just that. This year, roughly 1,000 schools — along with Boys and Girls Clubs, churches, teams, and local after-school and youth groups — will use the Say Something curriculum to teach kids in grades 6-12 how to recognize the observable warning signs of violence and other forms of self harm, including cutting, eating disorders, and substance, physical, or sexual abuse. The curriculum instructs students on how to act on those signs by safely and, if necessary, anonymously reporting potential threats to the right people.

The Say Something curriculum takes about 40 minutes to present, and Sandy Hook Promise then follows up with the schools or organizations to make sure they continue to sustain elements of the curriculum throughout the year through clubs and activities. The program is now also translated into Spanish.

The newest iteration of the Say Something curriculum focuses on social media, an area Hockley said is important because teens and adolescents are "all over" social media, and parents often have limited knowledge of channels such as Tumblr or Twitter.

Sandy Hook Promise hopes the Say Something program will encourage a culture of "looking out for one another" in schools and communities. According to the organization, it is already saving lives. In an Ohio school last year, a student leader who had been through the Say Something training overheard other students talking about placing bombs and shooting other students as they ran away from the school building. The student leader reported the plan to a school administrator, and the potential attackers were apprehended.

"Kids are seeing things that the adults in their lives are not, and they have the ability and the power to do something and save someone else," said Hockley.

Sandy Hook Promise has trained over 1 million children and adults across the country through its Know the Signs programs, including Say Something, since it was founded in 2013.